Chapter 7 The Roman World

INTRODUCTION

<>

While Alexander laid the foundations for Hellenistic civilization by carrying Greek culture and ideas into the heartland of the Persian Empire, further west the interplay of different cultures and civilizations also gave rise to a new variation on the theme of civilization. Phoenician cities had flourished in northern Africa and Spain since the late 2nd millennium B.C., while Greek cities dotted southern Italy and eastern Sicily in such profusion after the great period of Greek colonization that the region became known as Magna Graecia, or Greater Greece. These city-dwelling immigrants came into contact with various tribal peoples speaking Indo-European languages such as Celtic and Italic. In northern Italy the rather mysterious Etruscans, who may have migrated there from Asia Minor in several waves, had established their own highly structured and sophisticated kingdoms. As all these groups began to interact, a new civilization began to emerge in the western Mediterranean. The center of this new civilization was a small group of villages along the Tiber River not far from the western coast of Italy. Sometime in the early years of the 1st millennium B.C., these villages came together and organized themselves around a common market place, or forum. From this central forum grew the great imperial capital, Rome.

CHRONOLOGY

Section 1

Under Alexander the Great, Greek culture expanded

eastward into the ruins of the old Persian Empire. In many areas, the

new Hellenistic, or Greek-like culture that emerged under Alexander’s

successors remained little more than an artificial overlay, a culture of

the Greek-speaking elite that had little influence on the local cultures

and traditions of most people. This was particularly true in Egypt and

Mesopotamia, as well as among the Jews of Palestine. In other places,

however, such as Asia Minor, Syria, and far to the east in Bactria and

northern India, Greek civilization and culture did filter down to the

local level where it interacted with older traditions to produce a

blending of cultures. To the west too, Greek culture significantly

influenced emerging cultures and civilizations—particularly that of

Rome, which would soon conquer not only Greece itself but most of the

rest of the Hellenistic world around the Mediterranean Sea.

Geography and History

At even a first glance, the Italian peninsula would seem a logical place for the emergence of an imperial power that would dominate the Mediterranean region. The boot-shaped Italian peninsula juts south from Europe into the Mediterranean Sea nearly half way to Africa. It also lies almost halfway between the eastern and western boundaries of the Mediterranean world. In short, Italy provides the perfect land base from which people might be able to dominate the entire Mediterranean world.

To the north, the peninsula is protected, though not isolated, by

the high mountain range of the Alps. South, east, and west the sea

provides both protection and a means of rapid transportation. Up the

center of the peninsula, the Apennine Mountains divide the eastern and

western coasts. From north to south, Italy stretches some 750 miles,

with an average width of about 120 miles across. Much of the peninsula

is relatively rich country with a pleasant

climate, able to feed a large population. Compared to Greece, for

example, the interior of Italy provided much better soil, trees, and a

better balance between agriculture and the livelihood to be gained from

the sea.

Greeks, Carthaginians and Etruscans

Civilization came late to the western Mediterranean. Mesopotamia and Egypt had reached a sophisticated level of civilization long before anything occurred in the west. The first great civilization to emerge in Italy was established in Etruria, north of Latium, in modern-day Tuscany.

Etruria, from http://historyfacebook.wikispaces.com/file/view/etruscans.gif/30589536/etruscans.gif

Scholars disagree about whether the Etruscans came from Lydia, in Asia Minor, or were native Italians. What little we know about their original civilization is drawn from their cemeteries and the tombs they decorated and furnished for their dead. Judging from such evidence, they seem to have had a great zest for life. They danced, played hard at games, and feasted at great banquets. Women apparently played a much greater role in Etruscan society than in Greek or later Roman civilization.

<>

The Etruscans never established any single political entity in Etruria but organized themselves in a collection of independent cities. During their “Golden Age” in the 6th century B.C., however, the Etruscans dominated central Italy from the Po river to the bay of Naples. In the 5th century, pressure from Greeks and Celts, and revolts of the Latins forced them to retreat to Etruria proper, between the Arno and Tiber rivers. They greatly influenced Rome, which they controlled throughout the 500s.

From the middle of the 8th century Greek colonists settled in southern Italy and eastern Sicily. The region took the name of Greater Greece (Magna Graecia) because of the importance of Greek emigration in this region. Meanwhile, across the Mediterranean, on the North African coast, Carthage, a Phoenician colony founded in 814 B.C., headed a trading empire in the western Mediterranean, controlling the coasts of North Africa, Spain, western Sicily, as well as the islands of Corsica and Sardinia. Led by an aristocracy of merchants and possessing a powerful navy, Carthage could claim the title of "Queen of the western Mediterranean" in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C.

http://tjbuggey.ancients.info/images/maggrecia1.jpg

Surrounded by such influences, near the western coast in the

middle of the Italian peninsula, the city of Rome grew up from several

small villages grouped together around a central market, or forum.

According to tradition, Romulus and Remus, twin brothers who were raised

by a she-wolf, founded the city of Rome in 753 B.C. Whether such figures

actually existed or not, the city prospered at least partly from its

location. Located on the banks of the Tiber River

and only about 18 miles inland from the western coast of Italy, Rome was a

bridge-city, controlling access across the river, as well as any traffic

that might be travelling up- or down-river. Consequently, it not only lay

across valuable trade routes between northern and southern Italy, it

also had convenient access to the sea while at the same time being

protected from pirate attacks. Early Romans themselves appreciated the

strategic nature of the city's location, as the later Roman statesman, Cicero, acknowledged

in his explanation for the development of Rome’s empire:

“It seems to me that Romulus must at

the very beginning have [had] a divine intimation that the city would

one day be the site and hearthstone of a mighty empire; for scarcely

could a city placed upon any other site in Italy have more easily

maintained our present widespread dominion.” [Cicero (De Re Publica

II,5)]

The Romans. The people who established Rome were members of an Indo-European speaking group of peoples, known as Latins, who had migrated into the Italian peninsula from the northeast sometime around the beginning of the 1st millennium B.C. They were thus related to the Greeks, at least culturally if not ethnically, and spoke an Italic language that was relatively close to Greek. In Italy, the Latins came under the influence of the Greek city-states of the south, as well as the Etruscan civilization of northern Italy. Sometime after the founding of Rome, the city came under the rule of Etruscan kings, much as many Greek cities began life as small kingdoms.

In 509, however, the Romans threw out the last of their Etruscan monarchs, Tarquinius, and established a republic, in which representatives of the people, at first usually the wealthy landed nobles, but eventually including ordinary people called plebs, ruled the state. They remained at war with the Etruscans further north, as well as with their surrounding neighbors. Like the early Athenians, the Romans were a tribal people who yet learned how to organize themselves for city-life. Around them, meanwhile, the other Latin peoples continued to live a basically rural tribal existence as farmers and herders. Gradually, the Romans extended their control over these rural neighbors and incorporated them into a kind of Latin League.

Eventually, the Romans began to prevail over the Etruscans, partly because of their greater manpower and partly because of their development of a citizen army. In addition, although the Romans began to expand their city, they remained at heart a rural community. Roman citizens, both commoners and aristocrats called patricians, prided themselves on their connection with the soil. One famous story of early Rome for example, tells how the city was threatened by enemies; in their time of need, the people turned to their greatest general, Cincinnatus, who was plowing his own fields at the time. Leaving his plow, Cincinnatus defeated the Romans’ enemies—then promptly returned to his fields.

As the Roman population began to grow, so too did the need for more and more land. Soon, Rome had begun to conquer its neighbors and to settle its own surplus population on the newly-acquired land. Although, like the Greek cities, Rome too suffered from internal strife between aristocrats and commoners, in times of danger they could put these quarrels behind them and unite to confront their common foes. Moreover, much as had happened with the hoplites in Greece, Roman military victories not only provided more and more land for the peasants, thus alleviating their land-hunger, it also gave them a greater stake in the survival and growth of the city.

Although the rate of Roman expansion suffered a setback in 390

B.C., when a band of Celtic warriors swept down from the north, sacking

and burning the city, the Romans recovered quickly and Roman expansion

became even more rapid after the raid. By about 265 B.C., the Romans had

not only defeated the Etruscans of the north, conquering many of their

cities, they had also made themselves the masters of southern Italy,

which they conquered from the Greeks.

The foundation of Rome and the Royal period (753-509 B.C.).

Romulus and Remus. The Romans dated the foundation of their city to 753 B.C., when, according to tradition, twin sons born to a Vestal Virgin by the war god Mars established the city. Legend relates that the twins, grandchildren of king Numitor of Alba Longa, were condemned to death by their grand uncle who had usurped the throne. But the soldier charged with the deed could not bring himself to do it and abandoned the babies for wild beasts to devour. Instead, a she-wolf adopted them into her own litter and saved them by feeding them. Thereafter, the she-wolf became the symbol of Rome. Later the twins, Romulus and Remus, after giving back to their grandfather the throne of Alba Longa, left the city to found a new one, Rome.

"Capitoline Wolf, traditionally believed to be Etruscan, 5th century BC, with figures of Romulus and Remus added in the 15th century by Antonio Pollaiuolo. Recent studies suggest that it may be medieval, dating from the 13th century.[1] " From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romulus_and_Remus.

The legend of the foundation of Rome by Romulus and Remus was later associated with the Greek epic of the Trojan war. Aeneas, a Trojan prince, so the story went, had survived the final Greek assault on Troy and had fled the burning city leading a band of refugees. After long travels, the refugees eventually settled in Latium where Aeneas’s son founded Alba Longa, establishing himself as the first of a long dynasty of kings that culminated in Numitor, the grandfather of Romulus and Remus. In the 1st century A.D., the great poet Virgil immortalized this story of the Trojan origins of the Romans in his epic poem, the Aeneid.

Latin and Etruscan Kings. From 753 to 509 B.C. Rome was ruled by kings—at first Latin kings, then Etruscan kings (in the 6th century). The Etruscans were interested in Rome because of its strategic location: it was of crucial importance for their lines of communications between Etruria and Campania.

Under Etruscan rule, Rome began to prosper. The Etruscans transformed the dispersed villages into a city by paving the plain in the middle of the hills, by surrounding the city by a wall, by creating a solid political organization, and by strengthening the economy. From the Etruscans, the Romans learned and adopted many elements of civilization and culture: the alphabet; engineering expertise in irrigation and construction; the art of divination; and many others. Above all, perhaps, the Romans learned the art of social organization from the Etruscans.

The expulsion of the kings (509 B.C.). In 509, however, the Roman nobles expelled their last king, Tarquinius Superbus, as part of a general movement of liberation from Etruscan rule that was happening throughout Latium. The nobles proclaimed that Rome was now a republic in the Latin sense of the term res publica, or public property rather than the private property of a king. (see section iii)

Roman Conquest of the Mediterranean World

The conquest of Italy (509-272 B.C.). The Roman conquest of Italy should be considered in two phases divided by the sack of Rome by a raiding party of Gauls in 390 B.C. Before this disaster, the Romans had been able to take control over the neighboring tribes in Latium and the surrounding regions. They were starting the conquest of Etruria when a band of Gauls invaded from northern Italy. The Gauls defeated the Roman army on the field of battle, then sacked and burned Rome to the ground.

This set-back cancelled all the progress the Romans had achieved since 509 B.C. But it did not destroy the Romans’ spirit. As soon as the Gauls left, the Romans rebuilt their city and resumed their yearly campaigns against the tribes of central Italy. From that moment on the Romans would never stop expanding until they had established their dominion first over Italy, and then throughout the Mediterranean. By 338 B.C., Rome had gained control of the Latins and neighboring tribes (by 338 B.C.), and opened hostilities against the fierce tribally organized Samnites south east of Latium. It took three difficult wars to subjugate the Samnites (343-341; 316-304; 298-290 B.C.). In the process, the Romans established the predominance of an urban society throughout Italy that replaced the loose social structure of the tribal peoples.

Once in control of central Italy, the Roman legions moved south toward Magna Graecia. Rightly worried by Roman expansion, the city of Tarentum decided to appeal for help to Pyrrhus, king of Epirus. Pyrrhus, a relative of Alexander the Great, was one of the most brilliant generals of his time. He came to Italy with a well trained professional army of 35,000 men. The first two battles against Pyrrhus ended in outright defeats for Rome (279 and 278 B.C.). Nevertheless, the Romans stubbornly refused to acknowledge the superiority of their enemies or to negotiate with them as the normal rules of warfare between civilized countries suggested they should. Both the Romans’ stubborn refusal to negotiate and the casualties they inflicted on the Greek forces caused Pyrrhus to remark to one of his officers that with another such victory he would end up without an army! (Ever since, costly victories have been known as Pyrrhic victories.) In 276, the Romans faced Pyrrhus once more and finally were victorious.

The Pyrrhic War from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pyrrhic_War_Italy_en.svg

The Pyrrhic war made clear to everybody that the Romans could stand to lose battles but would end by winning the wars. The lesson was not forgotten. In 273, the king of Egypt, Ptolemy II, sent an embassy to seek a treaty of friendship with Rome. The great Hellenistic power of Egypt thus acknowledged the rising western power of Rome. Rome was now a power to be reckoned with in the Mediterranean world. The following year, the capture of the Greek city of Tarentum sealed the fate of southern Italy.

Roman Italy. It may be useful to interrupt here the history of the Roman conquest to reflect on the political organization of the conquest of Italy. The Romans proved extremely wise in their treatment of defeated enemies, preferring to transform them into “allies” rather than enslaved peoples. They imposed only two strict conditions: the defeated states must forfeit any independent foreign policy; and they had to provide a contingent of troops, known as auxiliaries, for service with the Roman army. Apart from these two requirements, Rome did not interfere in the domestic affairs, customs, or religion of their "allies".

By neither imposing a tribute nor interfering with the internal

affairs of the conquered cities, Rome avoided creating strong

resentments among the defeated Italians. In addition, by imposing her

own order on the Peninsula, Rome brought peace and security, two

advantages that many of the Italians appreciated. Before the Roman

conquest, the Italian tribes had been constantly fighting among

themselves. Now, under Roman hegemony they enjoyed a new era of peace

and stability at a minimum cost. At the same time, the Romans proved

exceedingly adept at practicing a policy known as “divide et impera,”

or “divide and rule.” By systematically negotiating separate

treaties with the different cities and tribes of Italy they deliberately

avoided creating an “Italian” consciousness, and lessoned the risk

that the new allies might join together against Roman rule. The

incorporation of Italian auxiliaries into the Roman military system

underpinned Roman authority and gave the Romans an immense reservoir of

potential military manpower. Roman armies were soon composed of equal

numbers of legions, made up of Roman citizens, and auxiliaries, drawn

from the Italian allies. From a military point of view, the Roman

conquest of the Mediterranean was actually a Romano-Italian achievement.

Conquest of the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.). Once in control of southern Italy, Rome soon decided to intervene outside of the peninsula, in Sicily. In agreeing to help the city of Messena against her enemy Syracuse, Rome came into conflict with Carthage. The Carthaginians controlled eastern Sicily and had no desire to see Rome in control of the straits between Italy and the island. Such a strategic position would pose a potential threat to their commercial ambitions. The first war between Rome and Carthage was fought in Sicily for 25 tears. It was a long and frustrating conflict since Rome was superior on land but the Carthaginian navy dominated at sea.

Only when the Romans realized that the war had to be won at sea and decided to build a navy could they win the conflict. The Romans did not challenge the Carthaginians at sea without difficulty. This new form of fighting had to be mastered and it cost them dearly: they lost more than 600 ships (and their crews and marines) during the war, most of them through lack of naval experience and competent leaders. Aware of their limitations as sailors, the Romans found an ingenious device to transform sea battle into land battle. They equipped their ships with boarding-bridges that were thrown on the enemies' ships and thus made it possible for Roman marines to board and fight as if they were on land. With this new technique of fighting, the Romans eventually not only prevailed on land but also overcame the Carthaginians at sea.

The results of this first Punic War were important for Rome. Carthage was forced to pay a heavy war indemnity and to abandon Sicily. The indemnity made it clear to the Romans that warfare might actually become a paying proposition. Control of Sicily reinforced this lesson. The Romans, for the first time faced with governing overseas territories, did not treat Sicily as they had conquered territories in Italy. Instead, they created their first province - that is, they ruled it directly with a governor and troops of occupation, and the imposition of a regular tribute. A few years later, in 238 B.C., taking advantage of a revolt among Carthage's mercenaries in North Africa, the Romans seized the islands of Sardinia and Corsica, which they transformed into their second province. The seizure of the two islands was contrary to all legal and moral principles but Carthage was in no condition to resist the aggression.

This act of brutal imperialism, however, generated hatred of Rome in Carthage. Some Carthaginians dreamed of revenge. Among them were the Barcids, a Carthaginian family who had emigrated to Spain after the loss of Sicily. They hoped to use Spain’s manpower to create an army. The son of Hamilcar Barca, the great general Hannibal, in 218 B.C. was to be the heir of this strategy when he departed from Spain at the head of a well trained army to invade Italy during the Second Punic War.

The second Punic war was one of the most tragic wars in Roman history. During its first three years Hannibal defeated the Romans in three great battles (Trebia in 218; Lake Trasimene in 217; Cannae in 216). By 215 Rome seemed on the verge of being destroyed. She had lost some 100,000 soldiers (either dead or prisoners), her southern Italian allies had defected to Hannibal, Sicily was no longer on her side, and the powerful king of Macedonia, Philip V, had made a military alliance with Hannibal. Nevertheless, Rome faced these trying times with all her energy and resources: the Senate took total control of the war effort and the whole Roman population stood behind their leaders. Eventually, Rome managed to regroup and finally to defeat the Carthaginians.

Carthage was severely punished. She lost her navy and Spain, as well as her independence in matters of foreign policy. As for Rome, the defeat of Carthage made her the leading power in the western Mediterranean. But the trauma of the second Punic war left indelible scars in the Roman psyche. Thereafter, for example, one Roman orator ended every speech he made in the Senate with the phrase, “Carthago delenda est!” meaning “Carthage must be destroyed.” Eventually, in 149 B.C. under arguable pretexts, the Romans declared war for the third time. After a siege of three years they finally took the city by force. They enslaved and evicted the remaining inhabitants and leveled Carthage itself. They even spread salt on the remains of the ancient city, as a symbolic dedication of the site to the gods of the underworld. In the meantime, the Romans secured their rule over northern Italy and Spain.

Conquest of the Eastern Mediterranean (215-133 B.C.). During the

Second Punic War, Macedonia

had been allied with the Carthaginians. As soon as the war was over, the

Romans declared war on Macedonia. They were victorious (197 B.C.). But

in intervening directly in the East, Rome quickly became involved in the

Hellenistic world – especially the Greek leagues and Syria. By 146

B.C., Rome was in control of the eastern Mediterranean.

Conclusion: The nature of Roman imperialism.

The Romans did not acquire their empire by following a rational plan of world domination. They acquired it piecemeal and for a variety of reasons - among them self-defense, fascination with military glory, responses to their allies' requests for help, a desire for military spoils and the riches of empire, and not least the militaristic character of the Roman people.

In addition to their success in defeating their enemies the Romans were remarkably successful in keeping their acquisitions. In addition to their military superiority, and their willingness to use force against any signs of revolt, the Romans owed their imperial successes to their treatment of their new subjects. They were not interested in direct exploitation nor in direct intervention in the domestic affairs of subjugated countries. They left the vanquished nations to enjoy their own customs, religions and cultures - as long as they abandoned all independence in foreign and military matters and paid a regular tribute. As in Italy, the Romans generally brought a greater peace and order than their new overseas provinces had previously known.

Early Roman Society (5TH-2ND CENTURIES B.C.)

Roman Republican Institutions

The expulsion of the last king in 509 B.C. left Roman society divided between the patricians (aristocrats by birth) and the plebeians (approximately 90% of the rest of the population). The patricians controlled every aspect of society: politics, religion, economy, military commands. They did not enjoy this absolute control for long, however. In fact, from the very beginning of the new Republic, plebeians challenged the patrician monopoly of power in what became known as the Conflict of the Orders (509 to 287 B.C.).

Much as in Greece during the same period, poor plebeians allied with a growing number of rich plebeians in the fight for economic reforms. They especially hoped to settle problems of debts and distribution of land. Rich plebeians were interested in political equality, access to public offices and priesthoods. It took them nearly two centuries to share political power on equal terms with the patricians. In the end, a new aristocracy emerged from this conflict, a patricio-plebeian aristocracy that was no longer based on birth but based on the holding of public offices. This new aristocracy, known as the nobilitas, consisted of those families whose ancestors had been elected to the highest office of the state, the consulship. This new kind of oligarchy reflected the strong feeling for serving the state in Roman society. Although restricted in numbers and access, the Roman oligarchy was not completely closed. New members could join by being elected to the consulship. After 287 B.C., however, Roman society was no longer divided between patricians and plebeians but between an oligarchy and the rest of the citizenry.

The new constitutional order that emerged out of the Conflict of the Orders consisted of three elements: the public offices, or magistracies; the Senate; and the popular assemblies. Access to public offices was limited to the richest members of the society. A high property qualification was required to follow a public career. After completing ten years of military service, a Roman politician would pursue his career by soliciting popular votes for a series of offices leading ultimately to the highest political office, the consulship. This career, known as the cursus honorum, was strictly regulated: there were minimum age requirements, mandatory progression from one office to another, delays between periods of holding office, and a prohibition against holding the same office more than once (except the consulship under certain emergency conditions.) Such rules insured that participants would become familiar with all aspects of the art of government: securing and distributing food supplies, organizing public games, accepting financial responsibilities, carrying out legal duties, and of course fulfilling military functions.

The magistrates were elected by the people either in the Centuriate Assembly for the highest offices (praetors, consuls, and censors) or by the assembly of the tribes for the minor magistracies. Wealthy citizens controlled the Centuriate Assembly by monopolizing the majority of the voting units. In the tribal assembly, citizens were distributed in 35 voting units based on where they lived, without considering their property qualifications. And yet, this assembly was controlled by the oligarchy mostly because of the lack of secret ballots and the importance of patronage. If successful in all stages of the cursus honorum, a candidate might be elected to the consulship. There were always two consuls, and the office controlled the highest power in civil and military matters. The most prestigious office, the censorship, could crown an already successful career. Two censors were elected every five years for 18 months to conduct the census of the whole population and to nominate new senators. Only the richest and best connected people could hope to become censors.

The Senate was the third element of the Roman republican political system and probably the most important one. It controlled foreign policy, military operations, and public finances. It was made up of 300 members chosen from among the elected magistrates, and the tenure was for life. The Senate was the most experienced council of Rome and enjoyed prestige and authority among both the current magistrates and the people. The Senate was not a legislative body—it only gave advice—but its opinion was usually followed.

The Roman republican system was neither democratic nor despotic. The Romans were a deferential people and did not challenge the control of the oligarchy. In addition, the Roman system of patronage, that is the division among citizens between patrons, rich and powerful citizens, and their clients, the common people who looked to them for protection and help in exchange for support in political matters, insured the control of the elite.

Until

133 B.C., the system worked well and the success of the Roman legions

year after year may have been partially responsible for this. Roman

citizens were proud of the achievement of their city and attributed it

to the excellence and common-sense practicality of its institutions. As

one Roman statesman explained Rome’s success:

“The reason of the superiority of the constitution of our city to that of other states is that the latter almost always had their laws and institutions from one legislator. But our republic was not made by the genius of one man, but of many, nor in the life of one, but through many centuries and generations.” [Cato (apud Cicero De Re Pub. II,1,2)]

The Roman Army

Rome’s successful expansion from a city-state into a major empire was due largely to its military superiority. The manpower of Italy sustained the Roman military machine. Roman armies were made up of Roman citizens and Italian allies in equal proportions. The citizens were organized into legions, while the allies acted as auxiliaries. Between the ages of 17 and 46, Roman citizens were liable for military service: 10 years in the cavalry or 16 years in the infantry. The time need not be served consecutively, and in cases of emergency a citizen might have to serve longer. Military service required a minimum property qualification since the Romans believed that one would only fight bravely if he had some property to protect at home.

At first the Romans used the phalanx formation but soon replaced it with a more elastic formation. They divided the phalanx into 30 units called maniples. Eventually, at the end of the 2nd century B.C., the Roman general Marius achieved a synthesis of the best elements of the phalanx system and that of the manipular system by reorganizing the legions into 10 cohorts. This system of cohorts provided both the flexibility for fighting in mountainous and broken terrain provided by the smaller maniples, as well as the power of the phalanx’s mass formation for fighting on open, flat terrain. The new cohort system remained the basic military organization of Rome until nearly the end of its imperial history.

Well disciplined and superbly trained, the Roman army was an army of foot soldiers rather than cavalrymen. Roman strategy was based on caution, organization, resilience, and high morale, rather than dashing and inspiring tactics. Until the reforms of Marius, the army reflected the make-up of Roman society—it was made up of citizen-soldiers. Indeed, all citizens were expected to be soldiers, and military glory was a major part of the Roman ethos, both among officers and men in the ranks. Republican Rome, in short, was very much a military society.

Republican Society

At the heart of Rome’s social structure was the family. Even the state reflected the basic structure and importance of the family in Roman life. The family in turn was like the state in small. Like other tribal peoples, the Romans were patriarchal. The head of the family, the paterfamilias, or family father, the oldest living male, had extensive powers over other members of the extended family. This included his wife, his sons with their wives and children, unmarried daughters, and the family slaves. One of the paterfamilias’s most important duties was to ensure the proper worship of the spirits of the family’s ancestors, on whom depended the family’s continuing prosperity—just as the prosperity of the state depended on the proper worship of the official gods of the state.

Families were grouped into gentes or clans, whose members claimed descent from a common, though often mythical ancestor. Within this basic family structure, Romans emphasized the virtues of the farmer-soldier—a stubborn breed, they valued above all authority, simplicity, and piety. Most families sustained themselves more or less independently on small farms which they managed themselves.

Roman women generally could not do anything without the intervention of a male guardian (the father, husband, son, or nearest male relative, as might be the case). Guardianship was an important legal question, even determining the kind of marriage a woman could engage in. In a marriage cum manu, for example, the guardianship passed from father to husband. However, the marriage contract might only provide for marriage sine manu, in which case the guardianship remained with the father (in which case, once her father died, the woman was actually free of guardianship and could act for herself (sui iuris) . The minimum legal marriage age was normally 12 for girls. In contrast to upper-class Athenian women, however, upper-class Roman women were not segregated from males in the home. They were free to go outside the home without escort.

Children were accepted in the family only if they were recognized and accepted by the father. As in Greece, the early Romans often exposed unwanted children. Adoption was an important aspect of Roman society, and adopted children, usually brought into a family to establish political alliances between families, or for the pupose of providing a strong heir to act as paterfamilias, were considered the full equals of natural children.

Education was carried on primarily at home. For boys it consisted mostly of military training, but also included basic reading, writing, and arithmetic. Under Greek influence, during the 2nd century a more literary education became popular, particularly in rhetoric and philosophy. Rome’s eventual conquest of Greece and the Hellenistic world brought many Greek tutors into rich households as slaves. As Rome adopted Greek culture, the upper classes of Roman society became largely bi-lingual, learning both Latin and Greek.

As Rome expanded, growing numbers of war captives became an important feature of society as slaves. As in Greece, slavery had always existed in Roman society, whether as a result of military conquest or because people had to sell themselves or their children to pay off debts. Romans were very liberal in giving freedom to their slaves, however, and freedmen also constituted a growing part of society.

Economically, Rome remained primarily dependent on agriculture.

At first, trade was marginal and industry nearly non existent. The

Romans had no independent coinage before the 3rd century. Although some

wealthy aristocrats began to accumulate large estates, in the early

years of the republic the economy was made up mostly of small farms

managed by a family and more or less auto-subsistent. Of far more

importance was the military nature of society—particularly once the

Romans discovered that conquests could be profitable.

Republican Culture

Before the 2nd century, Rome was too involved in military matters to devote much energy to the arts and literature. By the second century, however, the process of Hellenization had begun to transform Rome into a Hellenistic city. Drawing on a common Indo-European religious tradition, the Romans adopted Greek mythology and identified their own gods with those of Olympus.

Also like the Greeks, Romans viewed religion largely as a matter of state. Morality was less important than the exact performance of rituals through which both individuals and the state established the proper relationship with the gods. In fact, the Romans seem to have had a kind of contractual relationship with the gods—in exchange for the proper rituals, the gods would sustain the pax deorum, or “peace of the gods.” As one Roman statesman, Cicero, put it, “We have overcome all the nations of the world, because we have realized that the world is directed and governed by the gods.” To insure that the religious observances were done properly, the Romans established the posts of pontiffs, or priests, headed by the Pontifex Maximus, or Highest Priest, to act on behalf of the state in religious matters.

Believing also that the gods sent signs and warnings to human beings, the Romans also paid particular respect to the priests known as augurs, who specialized in interpreting these signs. Nothing important, in either family or public life, was undertaken without first consulting the augurs to see whether the gods approved or disapproved of an action. The signs, or auspices, came from observing the flight of birds, lightning, or the behavior of certain animals.

The Crises and

Fall of the Republic (133-27 B.C.)

As Rome grew from

a city-state in Italy to a world empire throughout the Mediterranean,

the character of Roman

society began to change. Under Hellenistic influences from the east,

individualism began to replace the old Roman commitment to duty to the

state. New wealth also bred growing competition within the ruling

classes, as aristocratic Romans competed for the offices and military

commands that might bring them even more fame and fortune. Under the

pressures of such rapid imperial expansion, Roman society began to

crumble, and people looked for a new balance of power within the state.

The challenges of finding this new balance would transform Rome once and

for all from a city-state to a great world empire, even as it forced the

old Roman sense of identity to expand and encompass even people beyond

the limits of the city of Rome itself.

The Consequences

of the Conquests

Rome

in the middle of the second century B.C. had no rival in the

Mediterranean world and yet she was still basically ruled by the

institutions of a small Italian city-state. A few elected magistrates

governed the empire without the help of any organized administrative

structure. Corruption of governors in the provinces

was a standard feature of Roman rule: competition for offices had

become so difficult that politicians were spending fortunes to get

elected, both legally and illegally. They had to make up for their

losses and they did so either through the booty they captured in war, or

the taxes they collected while governing the provinces.

Meanwhile, others were busy trying to take advantage of the

conquests to make their fortunes without feeling the need to participate

actively in politics: the equites , or knights, as they were known, were now too many and too

rich to ignore the importance of having access to political decision

making. As a result, the wealthy elite in Rome eventually divided into two competing

orders, the senators and the knights. As for the common people who

filled the legions, the conquests were now becoming a burden. After

serving long years away from Italy, many veterans were discharged only

to find that their farms had been sold or were in such financial trouble

that they must be abandoned. The farmer-citizen-soldiers who had built a

world empire increasingly found themselves condemned to join the growing masses of the

urban unemployed.

At the same time, foreign ideologies and religions began to

undermine the original fabric of Roman society. The traditional Roman

ideals of piety, faithfulness, duty and honor no longer satisfied a growing

number of citizens. Influenced by Greek political philosophy, many began

to question the selfishness of the Roman oligarchy. As Hellenistic

influences grew, individualism also began to conflict with the old Roman

emphasis on duty to the state.

The Roman

“Revolution”

As

the pressures of world empire grew, during the late 2nd and early 1st

century B.C. a revolution occurred in Roman political and social

institutions. As had happened earlier in Athens, the heart of this

revolution lay in the growing dissatisfaction of the plebs with the rule

of the Roman oligarchy.

The Gracchi.

In 133 B.C., Tiberius Gracchus, the tribune of the Plebs, pointed out to

the Roman people the tragic irony with which the old

farmer-citizen-soldier had been transformed into the urban unemployed

poor.

“The

wild beasts that roam over Italy have their dens and holes to lurk in,

but the men who fight and die for our country enjoy the common air and

light and nothing else... They fight and die to protect the wealth and

luxury of others. They are called the masters of the world, but they do

not possess a single clod of earth which is truly their own “

(Plutarch, Life of Tiberius Gracchus

9)

Gracchus’s

own ambition was to restore the dignity of his unhappy fellow citizens.

He presented a bill to limit access to public land and to redistribute

the land in the form of small farms to dispossessed farmers.

At first the bill was well received even by the senatorial

aristocracy which was also concerned about the growing poverty of the

Roman plebeians, a poverty that not

only undermined their morals but also kept a growing number of them out

of the draft since they could no longer afford the property

qualifications for the army. However, the tribune's motivation was soon

questioned by his cavalier attitude toward the traditional Roman

political system. Not only did Gracchus bypass the Senate and go

directly to the people but he forced the impeachment of a fellow tribune

who had vetoed his bill. He also infringed the Senate’s rights in

foreign matters, and took the unprecedent step of running for the

tribuneship a second time.

Eventually, fearing that he was planning to establish a tyranny,

the senators incited a lynch mob to kill Gracchus along with three

hundred of his followers. For the first time in Roman history the blood

of citizens was shed in the forum. Tiberius’s “crime” was that he

had undermined the traditional political order of Republican Rome by

questioning its oligarchic control. In effect, he had broken the social

consensus that had so far characterized Roman society, and thus began

the so-called Roman revolution. From 133 to 27 B.C., a series of reforms

and revolutionary steps led inexorably to the destruction of the

republican order. It was a period of disturbances that would end only

with the establishment of a new political order—the empire.

The revolution continued under Gaius Graccchus, Tiberius's

younger brother, who was elected tribune in 123 B.C. Gaius went much

farther than his brother in trying to reform the state. In addition to

accelerating the land law of his brother, he also gave enough political

power to the Equites to challenge the senators, thereby dividing the

Roman elite into two competing factions. He also took care of the common

people by regulating the grain supply of the city, a first step toward

what would soon become the distribution of free food to the people. In

the end, Gaius and his followers too were murdered by order of the

Senate. The oligarchy would not give up its control over Roman society

without a fight.

Marius. In

107 B.C., however, a social outsider named Marius was elected to the

consulship. Marius had become popular because of his military talents.

He was indeed a good general and had defeated King Jugurtha in Numidia

(modern Algeria) and Germanic invaders in southern France and northern

Italy. Marius carried the revolution begun by the Gracchi even

farther—not by attempting political reform, but by instituting

military reforms. Anxious to improve recruitment for the army, Marius

dispensed with the property qualifications for military service and

accepted in his army all who wanted to join. With these reforms, Marius

unintentionally changed the nature of the military from a civic-minded

force to a professional army.

Poor people now joined the army and attached themselves to a

general in hopes of sharing the booty of the campaigns and rewards of

land at the end of the war. To a large extant, armies became private

armies devoted to their general who held their economic future in his

hand. Marius had only tried to resolve a crisis in recruitment. His

successors, however, soon realized the political potential of such

professional armies. As usual, the occasion was a military crisis that

threatened Rome’s very survival.

The Social War.

In 90 B.C., the Italian allies of Rome rebelled. They had been trying to

gain Roman citizenship since the 120s but stubbornly both the Roman

Senate and the people’s assemblies had refused to share the privileges

of citizenship. The war between Rome and her Italian allies (known as

the "Social War", from the Latin socius, meaning

'ally') was one of the bloodiest conflicts in Roman history.

Italians had served side by side with the legionaries and were as good

soldiers as the Romans. In fact, the Social War resembled a civil war.

In the end, the rebels were defeated militarily – but they obtained

what they had been asking for: Roman citizenship. This was an important

step in the evolution of the Roman identity as well as the Roman empire.

With the extension of citizenship, Rome was no longer just one city –

it had become all of Italy.

Sulla.

The Social War had revealed the talent of one general in particular,

Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who as a result rose to the consulship in 88

B.C. Although Sulla had served under Marius, the two eventually

quarreled over who should receive the command of a war against

Mithridates, the king of Pontus in Asia Minor. Sulla saw the war as a

chance to revive the fortunes of his family, which although aristocratic

had become poor. As Marius and his faction tried to prevent Sulla from

taking command of the campaign against Mithridates (such campaigns were

potentially enormously lucrative and would certainly have restored

Sulla’s family fortunes), Sulla made the fateful decision to march on

Rome itself with his legions. In the civil war that followed, Sulla

emerged victorious in both Asia Minor and Italy, and established a

dictatorship in Rome.

Sulla seems to have been genuinely concerned about the growing

decay of the old Roman virtues and institutions. As dictator, he

implemented a comprehensive program of reform aimed at restoring the old

power of the Senate and the traditional oligarchy over the Republic.

After implementing these reforms, Sulla then voluntarily retired and

died peacefully on his own estate. His reactionary program did not long

survive him, however. It was soon challenged and overthrown by two

ambitious generals, Pompey and Julius Caesar.

The end of the

Republic.

Within

a generation of Sulla’s death, the old republic was practically dead.

The Republic fell largely because of the ambitions of three generals:

Pompey, Caesar, and Crassus. Combining themselves in a private alliance,

these three men conspired to control the Roman state through what came

to be known as the First Triumvirate, or rule of three men, in 60

B.C.. When Crassus died, however, Pompey and Caesar quarreled and civil

war once again wracked the empire. Eventually, Caesar defeated Pompey

and made himself master of Rome. In 44 B.C., the Senate declared Caesar

perpetual dictator and he was now king in all but name. Nevertheless, in

a last attempt to save the Republican constitution, a group of senators

led by Brutus and Cassius murdered Caesar in the Senate chamber itself

on the Ides of March—March 15— in 44 B.C.

Caesar's murder did not solve anything, however. In 43 B.C., a second triumvirate composed of Caesar’s heir and adopted son, Octavius, Mark Antony, Caesar’s loyal officer, and Lepidus, the Pontifex Maximus, was empowered by the Senate to take control of the affairs of the Republic. The Roman people had effectively abandoned the Republican principle. But this arrangement worked no better than that of 60 B.C. Soon Lepidus was pushed aside and civil war broke out between Mark Antony and Octavius. Eventually, Octavius defeated Antony and his ally, Cleopatra of Egypt, at the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. The common suicide of Antony and Cleopatra the following year marked the end of an epoch. Rome was now under the sole control of Octavius. The Republic was dead and a new period in Roman history was beginning.

The Pax Romana (27

B.C. - A.D. 180)

With the fall of

the Republic, a new phase of Roman development began under the

leadership of the so-called Julio-Claudian family. From a city-state,

the Republic had now emerged as a full-fledged empire. As the Julio-Claudians

sought to rationalize the empire’s government, republicanism was swept

away and replaced with a centralized imperial bureaucratic

administration. Under this strong, central government, Rome established

a period of peace, stability, and prosperity throughout the

Mediterranean world that would be remembered for generations.

Augustus and the

Principate

Back

in Rome in 29 B.C. Octavian faced the task of restoring order in the

empire. He had no intention of establishing a dictatorship but he had

come to realize that it was impossible to return to the old republican

system. A very astute politician, Octavian under the pretense of

"restoring the Republic" succeeded in establishing a new

political order which we call the empire. Octavian himself, however, was

very careful to avoid the title of king or emperor (the modern term came

from the Latin imperator, a title

given by soldiers to victorious generals). Instead, he presented himself

as princeps, the first citizen. He made clear that he had no more superior

powers than other magistrates and that his leadership came from his

higher moral authority (auctoritas).

In 27 B.C., the Senate gave him the honorific title of Augustus,

“the revered one”. In total control of the army, Augustus brought to

the Roman people what they were craving for: peace. After so many years

of anarchy, civil wars, and devastation the Romans wanted order and

stability. Augustus gave it to them and they praised him for that. For

more than forty years, Augustus remained at the head of the state, until

his death in A.D. 14, and this very long reign made possible a smooth

transition toward the new regime. Augustus wanted to be the guide but to

rule the empire in collaboration with the senators.

Augustus’s reign was a turning point in the history of Rome

since it concluded a century of disorder and create the foundation of a

new order, two centuries of peace and prosperity. Augustus divided the

administration of Rome and her empire between himself and the Senate

but, contrary to the latter, Augustus surrounded himself with a

professional, well-trained administration. Little by little the imperial

administration increased its field and at the end of the reign most

financial and administrative matters, as well as the military, was under

Augustus’s control.

In foreign affairs, Augustus initially hoped to put an end to

military adventures. But soon, once the army reorganized he started a

vast program of pacification in the West, especially in Gaul and Spain,

and a series of conquests that pushed the border of the empire to the

Danube river. His ultimate ambition was to push the border of the empire

from the Rhine to the Elbe river in order to shorten the length of his

northern frontier and so make it more defensible. When German tribes

under their war leader Arminius wiped out three Roman legions in 9 A.D.,

however, Augustus decided to retreat to the Rhine. He came to realize

that further conquests might overextend the resources of the empire in

finances and manpower. In the east he was more cautious and preferred to

use diplomacy to settle problems with the Parthian empire in Persia.

In domestic matters, the legacy of what became known as the

“Augustan Age” was even more impressive. Augustus initiated a vast

building program. He took special care of the city of Rome, organizing

its police force, fire brigades, and food and water supplies. He boasted

that he had found Rome a city of brick and had left it a city of marble.

Augustus also presided over moral and religious reforms. The gods

had made possible the empire, he argued, so it was just and wise to

praise them for it and show them respect. Temples were restored, new

ones were built, and many half-neglected cults were reorganized.

Preoccupied with what he saw as a growing moral decadence, Augustus

legislated against adultery and encouraged people to marry and have lots

of children.

Literature in the

Augustan Age

In

literature, the Augustan period is known as the Golden Age of Latin

literature, and includes many late-Republican writers such as the poet

Catullus, the philosopher Epicurus, the

orator-politician-lawyer-philosopher Cicero, and Julius Caesar himself,

whose mastery of the Latin language (especially in his war commentaries)

made him required reading for students of Latin prose. Realizing that

literature and the arts could enhance his fame, Augustus patronized the

arts. Literature flourished under his reign: the poets Horace and Ovid;

the historian Livy; and above all the poet Virgil who in his epic poem the

Aeneid tried to imitate

Homer by offering Rome a national epic that tied its origins to the

ancient city of Troy.

The Julio-Claudians

and the Flavians

The

successors of Augustus are known as the Julio-Claudians. They

consolidated imperial rule at the expense of the power of the Senate.

Consequently, our contemporary and later Roman sources are not always

very kind to them. They depict Tiberius (A.D. 14-37) as a suspicious and

cruel tyrant, Caligula (A.D. 37-41) as a monster, Claudius (A.D. 41-54)

as an old fool under the spell of his wives and freedmen, and Nero (A.D.

54-68) as an unpredictable and cruel tyrant. Such characterizations,

however, are rather unfair to them and overlook their contributions to

the Roman world.

Tiberius was a good soldier and a competent administrator despite

his difficult situation as the direct successor of the great Augustus.

Caligula was probably not a very balanced man but he was the first to

make the senators realize who now held the real power in

Rome. His reported announcement that he intended to have his favorite

horse, Incitatus,

serve as a consul was certainly a symbolic gesture intended to make them

understand the unlimited nature of the imperial power.

Claudius, perhaps even more than Augustus, should be remembered

as the founder of Roman imperial administration, the system that

presided over more than a century and a half of provincial prosperity

and stability. Claudius also did much to further extend Roman

citizenship to people in the provinces of the empire.

As for Nero, his passion for art and spectacles was not

understood by the senators. In addition his decision to build an

extravagant palace in Rome on land expropriated after the great fire of

A.D. 64 was unwise since many were convinced that he was responsible for

the fire in the first place. In an effort to exonerate himself, Nero

used the small Christian community as scapegoat, and thereby became the

first to begin the persecutions. The Christian tradition did not pardon

him for it and this has not helped his reputation. As revolt broke out,

Nero was forced to commit suicide, but soon the Romans were brutally

reminded of the fragility of the order of the Julio-Claudian emperors.

After Nero’s death in A.D. 69, civil war raged in the Roman

world. The Praetorian Guard, an imperial bodyguard first formed by Augustus, had already

intervened several

times in succession disputes, notably when they had forced Claudius to

accept the throne. As they once again interfered chaos ruled in Rome.

Eventually, four generals claimed the throne in turn. The last one,

Vespasian, finally managed to re-establish order.

During the reigns of Vespasian (69-79) and his two sons, Titus

(79-81) and Domitian (81-96), order, peace and prosperity returned to

the Roman world. These Flavians, as they are known, were not from

the old Roman aristocracy

like their predecessors, but from Italy. In fact, they had only recently

been admitted to the senatorial order. Despite such socially

questionable origins, however, they proved to be good

administrators, especially in financial matters.

The

"Golden Age"

In

96 a new dynasty established itself on the throne: the Antonines.

Five emperors presided over the destiny of the Roman empire for nearly a

century: Nerva (96-98), Trajan (98-117), Hadrian (117-138), Antoninus

(138-161), and Marcus Aurelius (161-180). They are known as the five

good emperors.

With the exception of Nerva, the Antonines were all of provincial

rather than Roman origins. Consequently, they continued the opening up

of Roman imperial society by admitting more and more members of the

provincial elites, particularly in the western provinces like Gaul and

Spain, into the Senate and the imperial administration. The Roman Empire

was no longer ruled solely by a small oligarchy drawn from the old Roman

aristocracy.

The Five Good Emperors were especially interested in providing

their subjects with a good, honest, and efficient administration, as

well as a sound imperial financial policy. Hadrian in particular spent

most of his time touring the provinces of the empire inspecting their

administration. The Antonine emperors managed to get along reasonably

well with the Senate, but they progressively increased the scope of

imperial administration. For example, they instituted a state program to

help poor parents raise and educate their children. To insure the

continuation of good government, all but Marcus Aurelius refused to

choose family members as successors, preferring instead to name the most

able successor possible as their heirs to the throne.

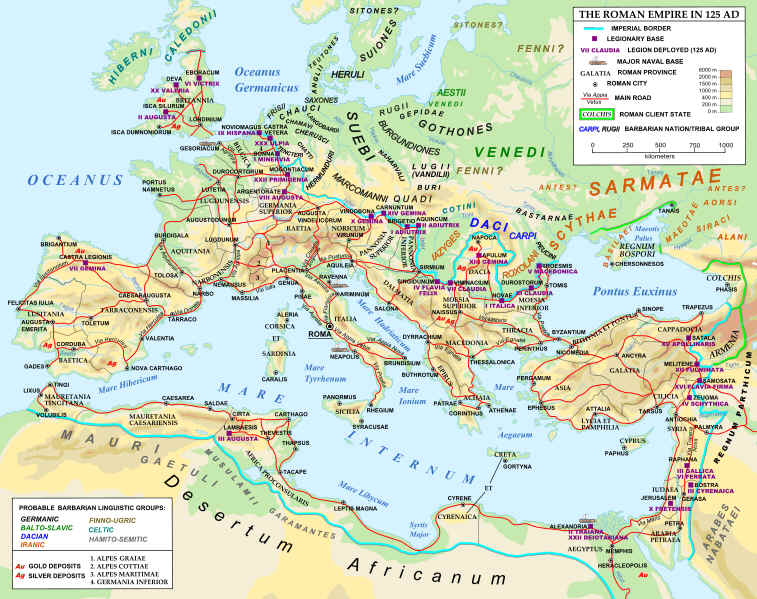

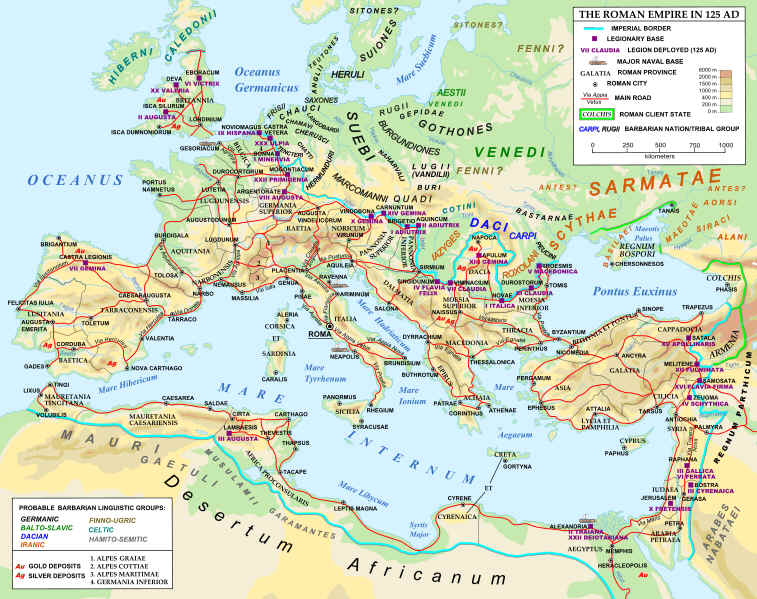

The Antonines also saw the Roman Empire reach the limits of its

territorial expansion. Trajan added Dacia (modern Rumania), Armenia,

Mesopotamia, and large parts of Arabia to the empire. His successor

Hadrian followed Augustus’s example, however, and to prevent the

empire from becoming overextended, he withdrew from all these eastern

additions except Dacia, which had valuable gold mines. Hadrian also

followed a policy of building defensive fortifications along the

empire’s frontiers, particularly on the Rhine and Danube Rivers and in

northern Britain, where he built a wall some 80 miles long to guard

against incursions into the Roman provinces by

“barbarian” tribal peoples.

Roman Imperial

Civilization

Several

essential characteristics helped the Romans build their empire and

maintain its peace. The Romans had a talent for ruling others and

maintained their authority through an efficient government both at home

and abroad. Law, military organization, and widespread trade and

transportation held the empire together and brought peace for more than

200 years. The period from the beginning of Augustus’s reign in 27

B.C. until the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 A.D. is known as the time

of the pax Romana, or Roman Peace.

Government.

The Roman government provided the strongest unifying force in the

empire. The government maintained order, enforced the laws, and defended

the frontiers. By the 2nd century A.D. the position of the emperor had

been well-established. He ruled without real opposition and was able to

insure the goodwill and cooperation of the elite in governing. Both in

the central administration and in the provinces, members of the

aristocracy participated in government, but all important decisions were

made by the emperors, most of whom were competent and conscious of their

responsibilities. From 27 B.C. to 180 A.D., only two short periods of

civil war disrupted the imperial government. In general, the system

initiated by Augustus proved successful and advantageous for the vast

majority of the inhabitants of the empire.

The provinces.

The Roman Empire was divided into provinces, territorial units governed

by a representative of Rome. During the Pax Romana, provincial

administration was both more efficient and fair than it had been under

the republic, largely because the government in Rome now kept a closer

check on provincial governors than before. Moreover, any citizen in the

provinces could appeal a governor’s decision directly to the emperor.

Through this provincial organization, the Roman Empire brought a

certain uniformity to the Mediterranean world. Cities were governed in

imitation of Rome, complete with their own local Senates and

magistrates. Local elites took pride in governing and embellishing their

cities. Theaters, amphitheaters, public baths, and temples could be seen

all over the empire from Britain to North Africa to Syria. Cities were

in fact the main beneficiaries of the empire’s prosperity. Wealth was

concentrated in the hands of the urban elites, who did everything

possible to improve the lives of the urban population and to entertain

them.

On the other hand, the vast majority of the population living in

the countryside saw little improvement in their living conditions.

Indeed, Roman civilization was primarily urban—for those living far

from the cities it had a limited impact, if any at all. Although the

Roman authorities maintained a level of peace never before known, they

were never able to eradicate brigandage and thievery in the countryside

altogether. Traveling outside the main centers of the Roman world was a

dangerous enterprise and, for most of the population, a luxury they

could not afford. For most people in the provinces, the only way to get

away from their native villages was to join the Roman army.

The army.

Augustus had reorganized the Roman army. It was divided almost evenly

between citizen legionaries and non-citizen auxiliaries. A legion had

approximately 5,500 men, and auxiliary units were roughly similar.

Legionaries served for 20 years, and auxiliaries for 25 years, at the

end of which service they would receive citizenship. An estimated

250,000 to 300,000 soldiers guarded the empire at the time of

Augustus’s death. Although this number rose under later emperors, the

total number of Roman soldiers probably never exceeded about

500,000—hardly an adequate number to defend some 6,000 miles of

borders.

The troops were stationed in great fortified camps at strategic

locations throughout the empire. However, there was no central, mobile

army in the empire that could be dispatched on short notice to a trouble

spot. In emergencies, the emperors had to move units from their own

areas to the threatened location. Thus, although the system was

efficient for low-intensity threats to security, it was not suited

coping with simultaneous threats at many different locations.

Law.

The Roman legal system combined two different approaches to law.

Stability in the system was achieved by laws, or statutes, passed by

popular assemblies or the Senate, which specified exactly what could or

could not be done and what the penalties were for breaking the law. In

addition, Roman law also tried to address questions of equity, or

fairness, by allowing magistrates, including provincial governors, to

decide at the beginning of their tenures what legal actions they would

hear. In judging such cases, the magistrates took into account new

social and economic circumstances that might require a modification or

adaptation of the law.

Roman law also unified the empire. The Romans distinguished

between two legal systems. The ius civile, or civil law, applied

between citizens. The ius gentium, or law of peoples, applied

between a citizen and a foreigner. In the ius gentium,

magistrates were not tied to traditional interpretations of the law but

were allowed to innovate as necessary to achieve fairness and justice.

Over time, however, these two approaches blended, and eventually Roman

law became a single, universal system. Even so, the Romans never imposed

their legal system on the provinces. They allowed local customs to

continue to guide the lives of provincials. Nevertheless, although such

local customs never fully disappeared, over time more and more peoples

adopted the Roman system because of its greater technical flexibility

and intellectual value. The extension of Roman citizenship also helped

the spread of the Roman legal system since citizens were by definition

subject to Roman laws.

The magistrates and the Senate were helped in legal matters by

professional jurists, the jurisconsults. These jurists were interested

in developing general legal principles that could be applied regardless

of the locale or the historical background of a problem. They wanted

above all to find legal principles that could apply to all human

beings—the ius naturale, or natural law. In later years, the

Roman system of law became the foundation for the laws of all the

European countries that had once been part of the Roman Empire, as well

as the laws of the Christian Church.

Trade and

transportation.

Throughout the time of the Pax Romana, agriculture remained the primary

occupation of people in the empire. A new type of agricultural worker, a

tenant farmer known as the colonus, began to replace

slaves on the large estates. Each of these farmers received a small plot

of land from the owner. In return, the colonus had to remain on the land

for a certain period of time and to pay the owner with a certain amount

of the crops. Most agricultural activities, however, continued to be

performed by independent farmers who were mostly interested in feeding

their families and had very little surplus to sell.

The Roman Empire provided enormous opportunities for commerce,

and the exchange of goods was relatively easy. Taxes on trade remained

low, and people everywhere used Roman currency. Rome and Alexandria

became the empire’s greatest commercial centers. Alexandria was

particularly important since Egypt was the granary of the empire,

producing the grain surpluses with which the emperors fed the urban

population of Rome itself. From the provinces, Italy imported grain and

raw materials such as meat, wool, and hides. From Asia came silks,

linens, glassware, jewelry, and furniture to satisfy the tastes of the

wealthy. India exported many products such as spices, cotton, and other

luxury products that Romans had never known before.

Manufacturing also increased throughout the empire during the Pax

Romana. Italy, Gaul, and Spain made inexpensive pottery and textiles. As

in Greece, most work was done by hand in small shops. To a considerable

extent, what made all this commercial activity possible was an elaborate

and extensive network of roads combined with safe sea lanes throughout

the Mediterranean.

Transportation greatly improved during the early period of the

empire as the Romans built up a great network of roads linking the

cities. Ultimately there were about 50,000 miles of roads binding the

empire together. Most roads, however, were built and maintained for

military purposes. Local roads were not paved and bad weather conditions

often made travel overland impossible. Although individual merchants

might travel the roads, giving way when necessary to the legions or the

imperial post riders, most goods were carried more cheaply and quickly

by sea. It was cheaper, for example, to transport grain by ship from one

end of the Mediterranean to the other than to send it 75 miles overland.

Consequently, one Roman priority was the suppression of piracy

throughout the Mediterranean.

Life in the Empire

The

Pax Romana provided prosperity to many people, but citizens did not

share equally in this wealth. Extreme differences separated the lives of

the wealthy from those of the poor. Rich citizens usually had both a

city home and a country home. Their residences included such

conveniences as running water and baths. Many of the nearly one million

residents of Rome, on the other hand, lived in crowded three and

four-storied tenement houses. Fire posed a constant threat in such

residences because of the torches the poor had to use for light and the

charcoal they used for cooking. In part to keep the poor of the cities

from rebelling against such conditions, public entertainments became a

major feature of civic life throughout much of the empire.

The Roman satirical poet, Juvenal, once noted with great disdain

that the Roman masses were interested in only two things: “panem et

circenses,” or bread and games. He was referring to the imperial

policy of providing free food and public entertainments to the

population of the city. In fact, a large part of being a public official

even in the days of the republic had been giving games and distributing

food for the people to enjoy. This was one reason public office was so

expensive.

Under Augustus 77 days were devoted to such public spectacles and

festivals every year. By the end of the 2nd century the number was up to

nearly 200 days. These games, originally to honor the gods, included

three main types of entertainment: drama and other performances in the

theaters: horse and chariot races in the Circus: and gladiatorial shows,

live fights to the death between individual warriors, in the

amphitheater.

Romans enjoyed the theater, especially light comedies and

satires. Performers such as mimes, jugglers, dancers, acrobats, and

clowns also became quite popular. Nothing, however, was more popular

than chariot racing. In Rome, the races were held in the Circus Maximus,

a racetrack that could accommodate 250,000 spectators. The races pitted

four professional teams, the Red, White, Blue, and Green, against each

other. Spectators bet heavily on the races, and especially enjoyed the

sometimes spectacular crashes that frequently occurred.

Romans were a violent people. They did not object to bloody

spectacles in the amphitheater, where wild animals were brought to fight

each other or professional fighters. Often, condemned criminals were

thrown into the arena to be torn to pieces by beasts. But the most

popular entertainment offered in the amphitheaters were gladiatorial

combats. Such shows could and often did end with the death of one or

both of the fighters, who were usually slaves. In Rome, these spectacles

were performed in the Coliseum, built under the emperors Vespasian and

Titus in the second half of the 1st century, which seated some 50,000

spectators.

The games were so popular that while they were in progress the

city could seem deserted—a situation that led the Stoic philosopher

Seneca to complain bitterly:

“Who respects a philosopher or any liberal

study except when the games are called off for a time or there is some

rainy day which he is willing to waste?”

Science,

Engineering, and Architecture

The

Romans were less interested in scientific research to increase knowledge

than in collecting and organizing information. Galen, a physician who

lived in Rome during the 100s A.D., for example, wrote several volumes

that summarized all the medical knowledge of his day. For centuries,

people regarded him as the greatest authority in medicine. Similarly,

people accepted the theories of Ptolemy in astronomy, partly because he

brought the knowledge and opinions of others into a coherent system.

Unlike the Greeks, who were primarily interested in knowledge for

its own sake, and preferred abstract reasoning to practical scientific

research, the Romans were eminently practical. They tried to apply the knowledge

they gained from the Greeks, for example, in planning their

cities, building water and sewage systems, and improving farming

methods. Roman engineers surpassed all other ancient peoples in their

ability to construct roads, bridges, aqueducts, amphitheaters, and

public buildings. Perhaps their most important contribution was the

development of a new type of concrete, which made such large

buildings possible in both financial and engineering terms.

Roman architects designed great public buildings—law courts,

palaces, temples, amphitheaters, and triumphal arches—for the

emperors, imperial officials, and the government. Although they often

based their buildings on Greek models, however, the Romans learned to

use the arch and the vaulted dome, features that allowed buildings to be

built much larger than the Greeks had been able to do. With such tools

and techniques, the Romans emphasized size as well as pleasing

proportions in their architecture.

The Crises of the

Empire and the Rise of Christianity

The end of the

reign of the Five Good Emperors showed signs of the troubles to come.

Military difficulties began on the Danube frontier, as Germanic tribes

began to press against the empire’s borders. Plague brought back by

the army from the east ravaged the empire. In Rome itself, famine

stalked the populace. Soon, the empire was best not only by challenges

from outside, but by a growing rot within.

The Crisis of the

200s

When

Marcus Aurelius decided on his successor in 180 A.D., he failed to show

his usual wisdom and foresight. Although his four predecessors had all

chosen their successors based on ability rather than ties of kinship,

Marcus Aurelius decided on his weak, spoiled son Commodus. Commodus

proved to be a disaster for the empire. According to Dio Cassius, a

contemporary Greek historian, after Marcus Aurelius’s death the Roman

Empire degenerated from “a kingdom of gold into one of iron and

rust.”

During most of the 200s, the empire experienced confusion,

economic decline, civil wars, and increasing military pressure on the

frontiers. Between 235 and 284, for example, 20 emperors reigned. All

but one died violently. From 226 onwards, the eastern borders of the

empire were threatened by the new Persian dynasty of the Sassanids.

Replacing the weak Arsacids, the Sassanids challenged Roman control of

the eastern provinces, adding a second front to the already restless

western frontier, where Germanic tribes continued to test the empire’s

defenses. From then on, military considerations became so increasingly

important for the empire that ultimately it became a kind of military

monarchy. The Emperor Septimius Severus, on his death bed in 211, had

only one piece of advice for his successor: “Enrich the soldiers and

scorn all other men.”

Internal decline

and reform. The

growing insecurity of civil wars and barbarian invasions affected many

aspects of Roman life. Brigandage and piracy reappeared and travel even

within the bounds of the empire became hazardous. Merchants hesitated to

send goods by land or by sea. It became difficult to collect taxes at a

time when military needs required them in ever increasing amopunts. In

212, the Emperor Caracalla granted Roman citizenship to all free people

of the empire. This was a logical conclusion to the movement of

progressive inclusion of the inhabitants of the empire in the Roman

identity, but it also had a more practical affect—only citizens paid

inheritance taxes and the emperor needed more money.

Inflation. As

taxes rose, however, the value of money declined. Since Rome had ceased