Chapter 7 The Roman World

Section 1

Under Alexander the Great, Greek culture expanded eastward into the ruins of the old Persian Empire. In many areas, the new Hellenistic, or Greek-like culture that emerged under Alexander�s successors remained little more than an artificial overlay, a culture of the Greek-speaking elite that had little influence on the local cultures and traditions of most people. This was particularly true in Egypt and Mesopotamia, as well as among the Jews of Palestine. In other places, however, such as Asia Minor, Syria, and far to the east in Bactria and northern India, Greek civilization and culture did filter down to the local level where it interacted with older traditions to produce a blending of cultures. To the west too, Greek culture significantly influenced emerging cultures and civilizations�particularly that of Rome, which would soon conquer not only Greece itself but most of the rest of the Hellenistic world around the Mediterranean Sea.

Geography and History

At even a first glance, the Italian peninsula would seem a logical place for the emergence of an imperial power that would dominate the Mediterranean region. The boot-shaped Italian peninsula juts south from Europe into the Mediterranean Sea nearly half way to Africa. It also lies almost halfway between the eastern and western boundaries of the Mediterranean world. In short, Italy provides the perfect land base from which people might be able to dominate the entire Mediterranean world.

To the north, the peninsula is protected, though not isolated, by the high mountain range of the Alps. South, east, and west the sea provides both protection and a means of rapid transportation. Up the center of the peninsula, the Apennine Mountains divide the eastern and western coasts. From north to south, Italy stretches some 750 miles, with an average width of about 120 miles across. Much of the peninsula is relatively rich country with a pleasant climate, able to feed a large population. Compared to Greece, for example, the interior of Italy provided much better soil, trees, and a better balance between agriculture and the livelihood to be gained from the sea.

Greeks, Carthaginians and Etruscans

Civilization came late to the western Mediterranean. Mesopotamia and Egypt had reached a sophisticated level of civilization long before anything occurred in the west. The first great civilization to emerge in Italy was established in Etruria, north of Latium, in modern-day Tuscany.

Etruria, from http://historyfacebook.wikispaces.com/file/view/etruscans.gif/30589536/etruscans.gif

Scholars disagree about whether the Etruscans came from Lydia, in Asia Minor, or were native Italians. What little we know about their original civilization is drawn from their cemeteries and the tombs they decorated and furnished for their dead. Judging from such evidence, they seem to have had a great zest for life. They danced, played hard at games, and feasted at great banquets. Women apparently played a much greater role in Etruscan society than in Greek or later Roman civilization.

<>

The Etruscans never established any single political entity in Etruria but organized themselves in a collection of independent cities. During their �Golden Age� in the 6th century B.C., however, the Etruscans dominated central Italy from the Po river to the bay of Naples. In the 5th century, pressure from Greeks and Celts, and revolts of the Latins forced them to retreat to Etruria proper, between the Arno and Tiber rivers. They greatly influenced Rome, which they controlled throughout the 500s.

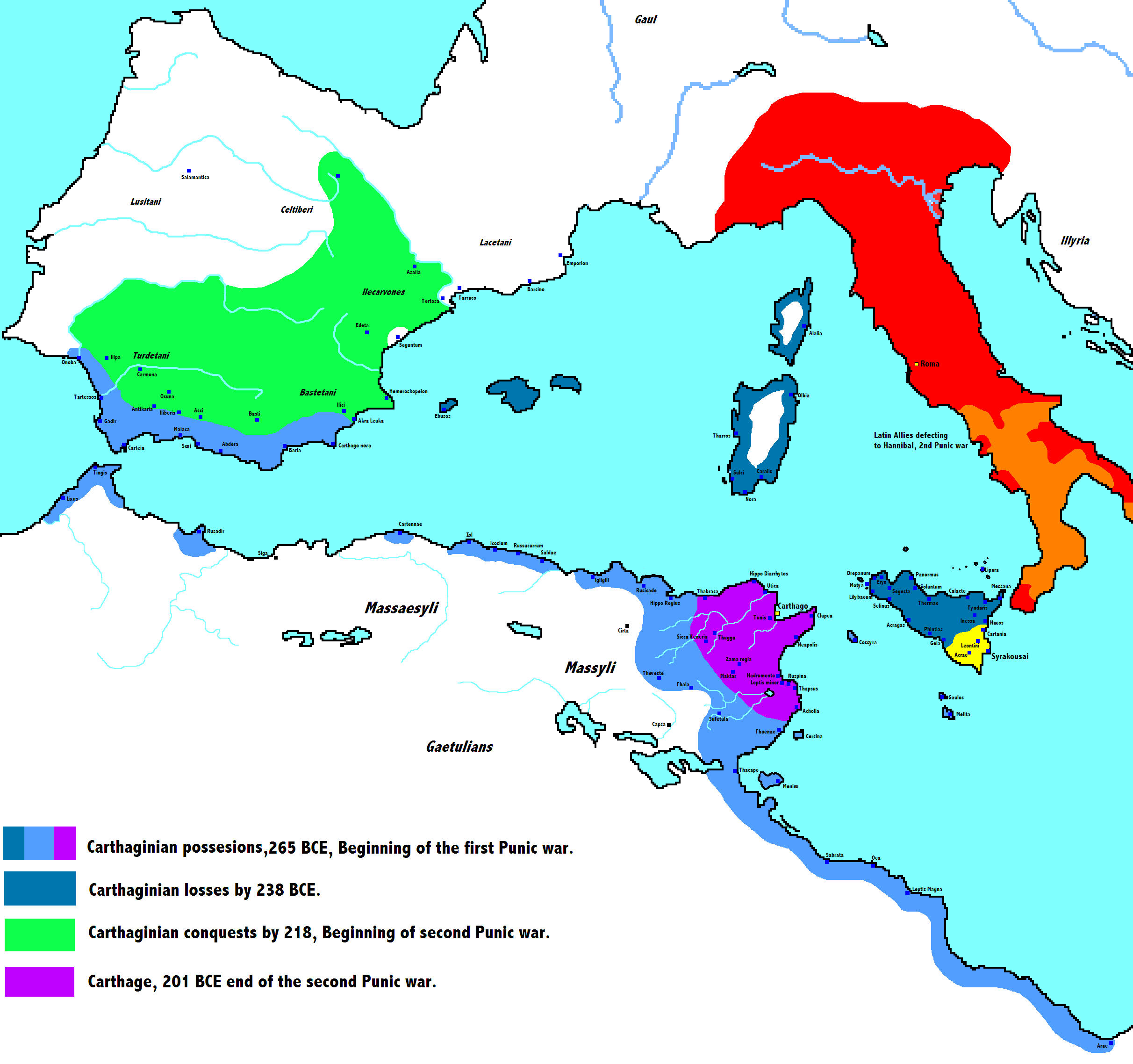

From the middle of the 8th century Greek colonists settled in southern Italy and eastern Sicily. The region took the name of Greater Greece (Magna Graecia) because of the importance of this Greek emigration. Meanwhile, across the Mediterranean, on the North African coast, Carthage, a Phoenician colony founded in 814 B.C., headed a trading empire in the western Mediterranean, controlling the coasts of North Africa, Spain, western Sicily, as well as the islands of Corsica and Sardinia. Led by an aristocracy of merchants and possessing a powerful navy, Carthage could claim the title of "Queen of the western Mediterranean" in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C.

http://tjbuggey.ancients.info/images/maggrecia1.jpg

Surrounded by such influences, near the western coast in the middle of the Italian peninsula, the city of Rome grew up from several small villages grouped together around a central market, or forum. According to tradition, Romulus and Remus, twin brothers who were raised by a she-wolf, founded the city of Rome in 753 B.C. Whether such figures actually existed or not, the city prospered at least partly from its location. Located on the banks of the Tiber River and only about 18 miles inland from the western coast of Italy, Rome was a bridge-city, controlling access across the river, as well as any traffic that might be travelling up- or down-river. Consequently, it not only lay across valuable trade routes between northern and southern Italy, it also had convenient access to the sea while at the same time being protected from pirate attacks. Early Romans themselves appreciated the strategic nature of the city's location, as the later Roman statesman, Cicero, acknowledged in his explanation for the development of Rome�s empire:

�It seems to me that Romulus must at the very beginning have [had] a divine intimation that the city would one day be the site and hearthstone of a mighty empire; for scarcely could a city placed upon any other site in Italy have more easily maintained our present widespread dominion.� [Cicero (De Re Publica II,5)]

The Romans. The people who established Rome were members of an Indo-European speaking group of peoples, known as Latins, who had migrated into the Italian peninsula from the northeast sometime around the beginning of the 1st millennium B.C. They were thus related to the Greeks, at least culturally if not ethnically, and spoke an Italic language that was relatively close to Greek. In Italy, the Latins came under the influence of the Greek city-states of the south, as well as the Etruscan civilization of northern Italy. Sometime after the founding of Rome, the city came under the rule of Etruscan kings, much as many Greek cities began life as small kingdoms.

In 509, however, the Romans threw out the last of their Etruscan monarchs, Tarquinius, and established a republic, in which representatives of the people, at first usually the wealthy landed nobles, but eventually including ordinary people called plebs, ruled the state. They remained at war with the Etruscans further north, as well as with their surrounding neighbors. Like the early Athenians, the Romans were a tribal people who yet learned how to organize themselves for city-life. Around them, meanwhile, the other Latin peoples continued to live a basically rural tribal existence as farmers and herders. Gradually, the Romans extended their control over these rural neighbors and incorporated them into a kind of Latin League.

Eventually, the Romans began to prevail over the Etruscans, partly because of their greater manpower and partly because of their development of a citizen army. In addition, although the Romans began to expand their city, they remained at heart a rural community. Roman citizens, both commoners and aristocrats called patricians, prided themselves on their connection with the soil. One famous story of early Rome for example, tells how the city was threatened by enemies; in their time of need, the people turned to their greatest general, Cincinnatus, who was plowing his own fields at the time. Leaving his plow, Cincinnatus defeated the Romans� enemies�then promptly returned to his fields.

As the Roman population began to grow, so too did the need for more and more land. Soon, Rome had begun to conquer its neighbors and to settle its own surplus population on the newly-acquired land. Although, like the Greek cities, Rome too suffered from internal strife between aristocrats and commoners, in times of danger they could put these quarrels behind them and unite to confront their common foes. Moreover, much as had happened with the hoplites in Greece, Roman military victories not only provided more and more land for the peasants, thus alleviating their land-hunger, it also gave them a greater stake in the survival and growth of the city.

Although the rate of Roman expansion suffered a setback in 390 B.C., when a band of Celtic warriors swept down from the north, sacking and burning the city, the Romans recovered quickly and Roman expansion became even more rapid after the raid. By about 265 B.C., the Romans had not only defeated the Etruscans of the north, conquering many of their cities, they had also made themselves the masters of southern Italy, which they conquered from the Greeks.

The foundation of Rome and the Royal period (753-509 B.C.).

Romulus and Remus. The Romans dated the foundation of their city to 753 B.C., when, according to tradition, twin sons born to a Vestal Virgin by the war god Mars established the city. Legend relates that the twins, grandchildren of king Numitor of Alba Longa, were condemned to death by their grand uncle who had usurped the throne. But the soldier charged with the deed could not bring himself to do it and abandoned the babies for wild beasts to devour. Instead, a she-wolf adopted them into her own litter and saved them by feeding them. Thereafter, the she-wolf became the symbol of Rome. Later the twins, Romulus and Remus, after giving back to their grandfather the throne of Alba Longa, left the city to found a new one, Rome.

The legend of the foundation of Rome by Romulus and Remus was later associated with the Greek epic of the Trojan war. Aeneas, a Trojan prince, so the story went, had survived the final Greek assault on Troy and had fled the burning city leading a band of refugees. After long travels, the refugees eventually settled in Latium where Aeneas�s son founded Alba Longa, establishing himself as the first of a long dynasty of kings that culminated in Numitor, the grandfather of Romulus and Remus. In the 1st century A.D., the great poet Virgil immortalized this story of the Trojan origins of the Romans in his epic poem, the Aeneid.

Latin and Etruscan Kings. From 753 to 509 B.C. Rome was ruled by kings�at first Latin kings, then Etruscan kings (in the 6th century). The Etruscans were interested in Rome because of its strategic location: it was of crucial importance for their lines of communications between Etruria and Campania.

Under Etruscan rule, Rome began to prosper. The Etruscans transformed the dispersed villages into a city by paving the plain in the middle of the hills, by surrounding the city by a wall, by creating a solid political organization, and by strengthening the economy. From the Etruscans, the Romans learned and adopted many elements of civilization and culture: the alphabet; engineering expertise in irrigation and construction; the art of divination; and many others. Above all, perhaps, the Romans learned the art of social organization from the Etruscans.

The expulsion of the kings (509 B.C.). In 509, however, the Roman nobles expelled their last king, Tarquinius Superbus, as part of a general movement of liberation from Etruscan rule that was happening throughout Latium. The nobles proclaimed that Rome was now a republic in the Latin sense of the term res publica, or public property rather than the private property of a king. (see section iii)

Roman Conquest of the Mediterranean World

The conquest of Italy (509-272 B.C.). The Roman conquest of Italy should be considered in two phases divided by the sack of Rome by a raiding party of Gauls in 390 B.C. Before this disaster, the Romans had been able to take control over the neighboring tribes in Latium and the surrounding regions. They were starting the conquest of Etruria when a band of Gauls invaded from northern Italy. The Gauls defeated the Roman army on the field of battle, then sacked and burned Rome to the ground.

This set-back cancelled all the progress the Romans had achieved since 509 B.C. But it did not destroy the Romans� spirit. As soon as the Gauls left, the Romans rebuilt their city and resumed their yearly campaigns against the tribes of central Italy. From that moment on the Romans would never stop expanding until they had established their dominion first over Italy, and then throughout the Mediterranean. By 338 B.C., Rome had gained control of the Latins and neighboring tribes (by 338 B.C.), and opened hostilities against the fierce tribally organized Samnites south east of Latium. It took three difficult wars to subjugate the Samnites (343-341; 316-304; 298-290 B.C.). In the process, the Romans established the predominance of an urban society throughout Italy that replaced the loose social structure of the tribal peoples.

Once in control of central Italy, the Roman legions moved south toward Magna Graecia. Rightly worried by Roman expansion, the city of Tarentum decided to appeal for help to Pyrrhus, king of Epirus. Pyrrhus, a relative of Alexander the Great, was one of the most brilliant generals of his time. He came to Italy with a well trained professional army of 35,000 men. The first two battles against Pyrrhus ended in outright defeats for Rome (279 and 278 B.C.). Nevertheless, the Romans stubbornly refused to acknowledge the superiority of their enemies or to negotiate with them as the normal rules of warfare between civilized countries suggested they should. Both the Romans� stubborn refusal to negotiate and the casualties they inflicted on the Greek forces caused Pyrrhus to remark to one of his officers that with another such victory he would end up without an army! (Ever since, costly victories have been known as Pyrrhic victories.) In 276, the Romans faced Pyrrhus once more and finally were victorious.

The Pyrrhic war made clear to everybody that the Romans could stand to lose battles but would end by winning the wars. The lesson was not forgotten. In 273, the king of Egypt, Ptolemy II, sent an embassy to seek a treaty of friendship with Rome. The great Hellenistic power of Egypt thus acknowledged the rising western power of Rome. Rome was now a power to be reckoned with in the Mediterranean world. The following year, the capture of the Greek city of Tarentum sealed the fate of southern Italy.

Roman Italy. It may be useful to interrupt here the history of the Roman conquest to reflect on the political organization of the conquest of Italy. The Romans proved extremely wise in their treatment of defeated enemies, preferring to transform them into �allies� rather than enslaved peoples. They imposed only two strict conditions: the defeated states must forfeit any independent foreign policy; and they had to provide a contingent of troops, known as auxiliaries, for service with the Roman army. Apart from these two requirements, Rome did not interfere in the domestic affairs, customs, or religion of their "allies".

By neither imposing a tribute nor interfering with the internal affairs of the conquered cities, Rome avoided creating strong resentments among the defeated Italians. In addition, by imposing her own order on the Peninsula, Rome brought peace and security, two advantages that many of the Italians appreciated. Before the Roman conquest, the Italian tribes had been constantly fighting among themselves. Now, under Roman hegemony they enjoyed a new era of peace and stability at a minimum cost. At the same time, the Romans proved exceedingly adept at practicing a policy known as �divide et impera,� or �divide and rule.� By systematically negotiating separate treaties with the different cities and tribes of Italy they deliberately avoided creating an �Italian� consciousness, and lessoned the risk that the new allies might join together against Roman rule. The incorporation of Italian auxiliaries into the Roman military system underpinned Roman authority and gave the Romans an immense reservoir of potential military manpower. Roman armies were soon composed of equal numbers of legions, made up of Roman citizens, and auxiliaries, drawn from the Italian allies. From a military point of view, the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean was actually a Romano-Italian achievement.

Conquest of the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.). Once in control of southern Italy, Rome soon decided to intervene outside of the peninsula, in Sicily. In agreeing to help the city of Messena against her enemy Syracuse, Rome came into conflict with Carthage. The Carthaginians controlled eastern Sicily and had no desire to see Rome in control of the straits between Italy and the island. Such a strategic position would pose a potential threat to their commercial ambitions. The first war between Rome and Carthage was fought in Sicily for 25 tears. It was a long and frustrating conflict since Rome was superior on land but the Carthaginian navy dominated at sea.

Only when the Romans realized that the war had to be won at sea and decided to build a navy could they win the conflict. The Romans did not challenge the Carthaginians at sea without difficulty. This new form of fighting had to be mastered and it cost them dearly: they lost more than 600 ships (and their crews and marines) during the war, most of them through lack of naval experience and competent leaders. Aware of their limitations as sailors, the Romans found an ingenious device to transform sea battle into land battle. They equipped their ships with boarding-bridges that were thrown on the enemies' ships and thus made it possible for Roman marines to board and fight as if they were on land. With this new technique of fighting, the Romans eventually not only prevailed on land but also overcame the Carthaginians at sea.

Only when the Romans realized that the war had to be won at sea and decided to build a navy could they win the conflict. The Romans did not challenge the Carthaginians at sea without difficulty. This new form of fighting had to be mastered and it cost them dearly: they lost more than 600 ships (and their crews and marines) during the war, most of them through lack of naval experience and competent leaders. Aware of their limitations as sailors, the Romans found an ingenious device to transform sea battle into land battle. They equipped their ships with boarding-bridges that were thrown on the enemies' ships and thus made it possible for Roman marines to board and fight as if they were on land. With this new technique of fighting, the Romans eventually not only prevailed on land but also overcame the Carthaginians at sea.

The results of this first Punic War were important for Rome. Carthage was forced to pay a heavy war indemnity and to abandon Sicily. The indemnity made it clear to the Romans that warfare might actually become a paying proposition. Control of Sicily reinforced this lesson. The Romans, for the first time faced with governing overseas territories, did not treat Sicily as they had conquered territories in Italy. Instead, they created their first province - that is, they ruled it directly with a governor and troops of occupation, and the imposition of a regular tribute. A few years later, in 238 B.C., taking advantage of a revolt among Carthage's mercenaries in North Africa, the Romans seized the islands of Sardinia and Corsica, which they transformed into their second province. The seizure of the two islands was contrary to all legal and moral principles but Carthage was in no condition to resist the aggression.

This act of brutal imperialism, however, generated hatred of Rome in Carthage. Some Carthaginians dreamed of revenge. Among them were the Barcids, a Carthaginian family who had emigrated to Spain after the loss of Sicily. They hoped to use Spain�s manpower to create an army. The son of Hamilcar Barca, the great general Hannibal, in 218 B.C. was to be the heir of this strategy when he departed from Spain at the head of a well trained army to invade Italy during the Second Punic War.

The second Punic war was one of the most tragic wars in Roman history. During its first three years Hannibal defeated the Romans in three great battles (Trebia in 218; Lake Trasimene in 217; Cannae in 216). By 215 Rome seemed on the verge of being destroyed. She had lost some 100,000 soldiers (either dead or prisoners), her southern Italian allies had defected to Hannibal, Sicily was no longer on her side, and the powerful king of Macedonia, Philip V, had made a military alliance with Hannibal. Nevertheless, Rome faced these trying times with all her energy and resources: the Senate took total control of the war effort and the whole Roman population stood behind their leaders. Eventually, Rome managed to regroup and finally to defeat the Carthaginians.

Carthage was severely punished. She lost her navy and Spain, as well as her independence in matters of foreign policy. As for Rome, the defeat of Carthage made her the leading power in the western Mediterranean. But the trauma of the second Punic war left indelible scars in the Roman psyche. Thereafter, for example, one Roman orator ended every speech he made in the Senate with the phrase, �Carthago delenda est!� meaning �Carthage must be destroyed.� Eventually, in 149 B.C. under arguable pretexts, the Romans declared war for the third time. After a siege of three years they finally took the city by force. They enslaved and evicted the remaining inhabitants and leveled Carthage itself. They even spread salt on the remains of the ancient city, as a symbolic dedication of the site to the gods of the underworld. In the meantime, the Romans secured their rule over northern Italy and Spain.

Conquest of the Eastern Mediterranean (215-133 B.C.). During the Second Punic War, Macedonia had been allied with the Carthaginians. As soon as the war was over, the Romans declared war on Macedonia. They were victorious (197 B.C.). But in intervening directly in the East, Rome quickly became involved in the Hellenistic world � especially the Greek leagues and Syria. By 146 B.C., Rome was in control of the eastern Mediterranean.

Conclusion: The nature of Roman imperialism.

The Romans did not acquire their empire by following a rational plan of world domination. They acquired it piecemeal and for a variety of reasons - among them self-defense, fascination with military glory, responses to their allies' requests for help, a desire for military spoils and the riches of empire, and not least the militaristic character of the Roman people.

In addition to their success in defeating their enemies the Romans were remarkably successful in keeping their acquisitions. In addition to their military superiority, and their willingness to use force against any signs of revolt, the Romans owed their imperial successes to their treatment of their new subjects. They were not interested in direct exploitation nor in direct intervention in the domestic affairs of subjugated countries. They left the vanquished nations to enjoy their own customs, religions and cultures - as long as they abandoned all independence in foreign and military matters and paid a regular tribute. As in Italy, the Romans generally brought a greater peace and order than their new overseas provinces had previously known.