Chapter 10 The Rise of Islam

Section 1

In 610 A.D. the prophet Muhammad began to receive a series of

revelations that would become the foundation of the faith of Islam.

Renowned for his piety and wisdom, for the remainder of his life

Muhammad spread his message to the Arabs. By the time of his death in

632, virtually every tribe in the Arabian Peninsula had enlisted under

the banners of Islam and given their allegiance to its prophet.

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

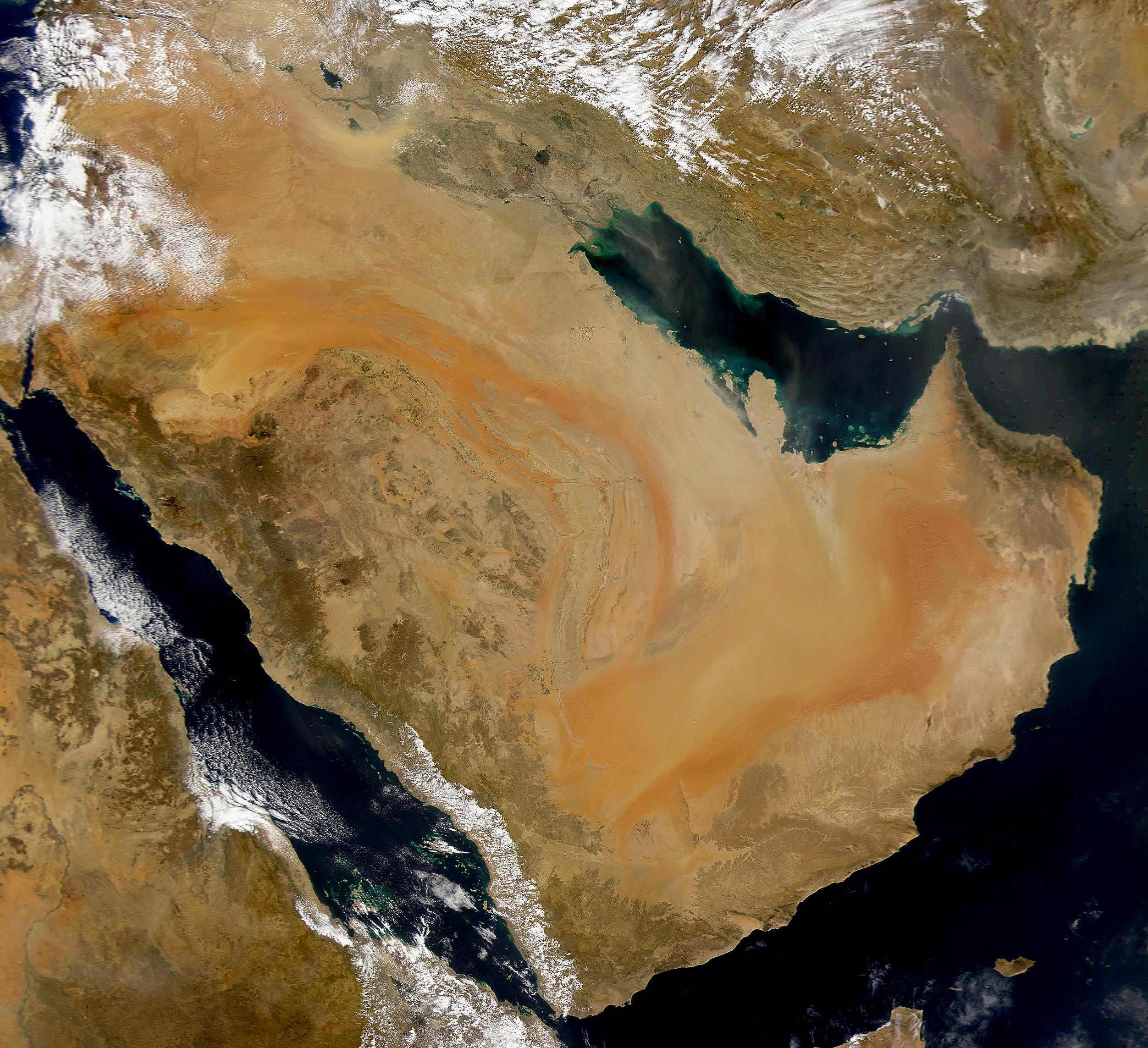

The Arabian Peninsula—a vast plain of deserts and small mountains—lies

across the Red Sea from the northeastern coast of Africa. It stretches

about 1,400 miles from the Syrian Desert in the north to the Arabian Sea

in the south and about 1,200 miles from the Red Sea on the west to the

Persian Gulf on the east. While the majority of the peninsula is desert,

the southwest corner, known as Yemen, has fertile mountain lands and

good ports.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Arabian_Peninsula_dust_SeaWiFS-2.jpg/280px-Arabian_Peninsula_dust_SeaWiFS-2.jpg

Agriculture and trade in the

southwest. As early as

the twelfth century B.C. people in Yemen created wealthy kingdoms based

on agriculture and trade. They built great dams and irrigation networks

to grow wheat and other crops. The Yemeni also extracted tree sap to get

frankincense and myrrh, resins used for incense. Traders grew wealthy

exporting myrrh, frankincense, and spices such as cinnamon, all of which were

highly prized and extremely valuable in the markets of Africa, Southwest Asia, and Europe.

Over time, thanks to their strategic position on both the sea and

land trading routes that linked the Mediterranean region with the Indian

Ocean, the merchants and rulers of Yemen also came to control

the trade in spices and silks between Asia, India, and the

Mediterranean. As trade made them fabulously wealthy, it also made them

targets for more powerful states. The country was invaded at

various times by Ethiopians, Romans, Persians, and Byzantines. Both

trade and conquest exposed Yemen to many new ideas and cultures. It

became home to many religions, each with its own temples and priests.

These influences made Yemen a center of great cultural diversity from

which new ideas spread along the trade routes.

Oases, towns, and deserts. In

much of the rest of the peninsula, the merciless glare of the desert sun

and the lack of water prevented people from growing crops. In this harsh

environment, most people survived by herding animals. Called Bedouin,

they lived in tents and moved from place to place, herding sheep, goats,

and camels. Since struggle over water rights and livestock was a way of

life in the harsh conditions of the desert, the Bedouin were mobile,

armed, and used to fighting.

Some Bedouin settled in oases,

shady areas with water sources, where they could grow crops such as

grain and dates. In some oases, especially along trade routes, towns

sprang up. The northwestern Arabian town of Yathrib, for example, was

located in an oasis with fertile soil that produced large date crops.

Within the oasis lived farmers and herders. In the town lived merchants

and craftsmen serving the caravan trade between Yemen and the

Mediterranean.

Some Bedouin came to depend entirely on the caravan trade for

their living. South of Yathrib, in a rocky valley about 30 miles from

the Red Sea, local Bedouins and immigrants from Yemen turned the town of

Mecca into a major caravan center. Although Mecca had not been built in

a fertile oasis, it was located near the intersection of two trade

routes and controlled the well of Zamzam. It was also the site of an

area that many surrounding peoples believed to be sacred. Meccans lived

by supplying the caravan trade and the pilgrims who came to pray at the

sacred site. [1][1]

Relations between the nomadic Bedouin and the people of the towns

and oases could be uneasy-- the nomads were likely to raid both. Often,

however, merchants and Bedouin would reach an agreement. Merchants would

pay for "protection" and market the Bedouin’s fine leather

goods, rugs, and woven cloth.

ARAB SOCIETY AND CULTURE

Bedouin culture influenced the political and social organization of

Arabia. Like the Bedouin, all Arabs organized themselves into clans and

tribes. They cherished family relationships because people depended on

families for survival. "Take for thy brother whom thou wilt in the

days of peace," went one Arab verse, "But know that when

fighting comes thy kinsman alone is near."[2][2] Arab society was also

paternalistic. Fathers made important decisions within the family and

took part in politics. Male clan leaders advised the shaykh,

the leader of the tribe, but all the men of the tribe often made major

decisions in a kind of tribal democracy.

Women rarely took part in politics although their advice was

often sought on important community issues. Women's primary role was

that of mother. They also contributed to the group through such

activities as spinning and weaving. Although Arab society was

paternalistic, women had considerable freedom. In towns they could own

property and businesses. In the desert, some tribes allowed women to

have more than one husband, just as men could have more than one wife.

Arab values reflected their struggle for survival in a harsh

environment. They prized above all loyalty, honor, courage and

generosity. Arab leaders displayed loyalty and generosity by giving

feasts and presents to their followers. For poorer members of society,

such generosity in times of want could mean the difference between life

and death. Hospitality to guests was also a matter of honor and sacred

obligation.

As Arabs settled down in the relative security of towns and

oases, tightly knit tribal organization became less essential for

survival. Tribal loyalties began to give way to those of immediate

family and clan. Growing wealth and the accumulation of private property

that was part of merchant life also caused changes. Inheritance disputes

could cause conflict within families. As clans vied for power, tribal

loyalties were often forgotten.

In Mecca, for example, strife among the different clans of the

ruling Quraish tribe became particularly intense in the last half of the

sixth century. The Umayyad clan displaced others as its members sought

to control trade and town government. Such rivalry, however, increased

people's sense of insecurity. As they struggled to recover a sense of

personal security, new ideas began to circulate.

THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD

In 613, Muhammad, a member of a relatively poor clan of the ruling tribe,

began to preach an especially powerful set of new ideas in Mecca.

Muhammad had been born in Mecca around 570.

His early life was not easy. His merchant father died before he

was born, and his mother died when he was six. His grandfather, and an

uncle, Abu Talib, raised him. As a young man, Muhammad became the

manager of a caravan business owned by Khadija, a wealthy widow. At the

age of 25, he married Khadija, who was 15 years older. They had three

sons and four daughters, but experienced tragedy as all but one

daughter, Fatima, died young.

In his early years, Muhammad may have practiced the religious

traditions of his city. Although some wandering Arab holy men had

already begun to preach the existence of only one god, most people in

Arabia were polytheists. They worshipped their gods and goddesses at

special shrines. One of the most important shrines, the Kaaba, was in

Mecca. Many people journeyed there every year, even setting aside blood

feuds to trade and worship. As a caravan manager traveling the trade

routes, Muhammad also probably became familiar with Jewish and Christian

ideas. Perhaps around the campfires at night, with the stars shining

brilliantly above in the desert sky, Muhammad heard Jewish and Christian

merchants telling stories from the Torah and the Gospels.

From the time he was young, Muhammad often escaped the crowded

life of Mecca by going to the nearby hills to pray and meditate. One

day, when he was about 40, he went to meditate in a cave among the

hills. Suddenly, in the silence of the cave, according to the Muslim

tradition, he heard a voice commanding him, "Recite! Recite!"

Startled, Muhammad asked what he was to recite. The voice answered:

"Recite: in the name of thy Lord who

created,

created man of a blood-clot.

Recite: and thy Lord is the most

bountiful,

who taught by the pen,

taught man what he knew not."3

After arguing a bit with the voice, which identified itself as the angel

Gabriel, Muhammad agreed to carry the message to others. Over the next

twenty-two years, he received many more revelations, which became the Qur'an,

the holy book of Islam.

Muhammad's message. Muhammad's

earliest revelations contained two simple messages. First, there was

only one God: "Say God is One; God the Eternal: He did not beget

and is not begotten, and no one is equal to Him." Second, those who

accepted God's message must obey his will. In doing so they formed a

special community, the umma,

in which all believers were equals. They must look out for each other,

especially the weak or needy.

To the Arabs who worshipped many gods, Muhammad's message was

radical. Although called Allah, the name of one of the Arabs' most

important gods, Muhammad 's God was the God of the Christians and Jews.

Muhammad believed that just as God had sent his divine message to

humanity through prophets, including Abraham and Jesus, God was sending

new revelations through him.

The flight from Mecca. As

Muhammad preached these revolutionary ideas of social equality and

monotheism, the merchant rulers of Mecca became alarmed. Muhammad’s

claim that all the faithful belonged to a single Islamic community

seemed to threaten tribal and clan authority. His rejection of

polytheism also seemed to a threat to those who profited from the annual

pilgrimages to the Ka`ba. The rulers of Mecca soon began to harass the

prophet and his small band of followers.

Meanwhile, however, Muhammad's reputation for both piety and

justice spread beyond Mecca. Nearly 10 years after he had begun

preaching in Mecca, a delegation of tribesmen from Yathrib asked him to

settle in their city and serve as a kind of arbitrator or referee among

the feuding tribes of the oasis. With the Meccan leaders growing

increasingly hostile to the umma, in 622, Muhammad accepted the offer

and traveled to Yathrib with many of his followers. This journey became

known in Islamic history as the hijra,

the flight, or migration.

Muhammad's arrival in Yathrib marked an important milestone in

Islamic history. In Yathrib, he governed as both a spiritual and a

political leader. Yathrib itself was renamed Medina, or City of the

Prophet. Later, Muslims marked the year of the hijra

as the beginning of the Islamic calendar. In Mecca, Muhammad had

emphasized that he was continuing the tradition of Jewish and Christian

prophecy. When Jewish tribes in Medina refused to acknowledge him as a

prophet, however, he moved away from Jewish and Christian practices.

Instead of facing their holy city of Jerusalem while praying, for

example, in Medina a new revelation commanded the Muslims to face Mecca

and the Kaaba instead.

From Medina, Muhammad began to convert the desert tribes. With

their help, the Muslims also began to raid the Meccans’ caravans. In

630, after several years of warfare, Mecca gave in and opened its gates

to the prophet. The Meccans too now accepted the new faith. Muhammad

destroyed the pagan idols in the Kaaba so that Muslims could make the

pilgrimage to worship God there as commanded by the revelations. After

this victory, most of the Arabian tribes acknowledged Muhammad's

leadership and the power of Islam. When he died in 632 at his home in

Medina, the Prophet had laid the groundwork for a new religion that

would soon spread from Arabia to the rest of the world.