Chapter 11 A New Civilization in Western Europe: the Rise of Latin Christendom, 476-1350

Section 4

INTERNET RESOURCES: The Crusades

During the six centuries that followed the fall of Rome, civilization in

western Europe was on the defensive. Climate change, pandemic disease and wave

after wave of invaders from north, south and east, combined to force the retreat

of civilized life. After about 1000 A.D., however, the barbarian invasions

generally ended, the climate improved and pandemic diseases lessened. Having

survived all these challenges, under the auspices of Christianity and the Roman

Church western Europeans began to re-create civilization in a form that retained

much of the heritage of the late Roman Empire. Yet even as the west began to

revive, the last remnants of Roman imperial rule in the east still struggled to

defend the frontiers of Christendom against invaders. The rise of the Saljuq Turks

had seriously threatened

the Byzantine Empire. When the Byzantine emperor appealed to Pope Urban II for

help in recovering his lost provinces from the Turks in the 1090s, Urban urged

men of all ranks to wage a great war, or Crusade, to recover the Holy Land for

Christ. Throughout Europe people heeded the call. Some were inspired by faith

and the hope of being cleansed of sin. Many knights sought more earthly rewards

like land[55]

or plundered wealth. Merchants saw a chance to improve their profitable trade

with Byzantium.[56]

Some simply wanted the adventure.

The Early Crusades

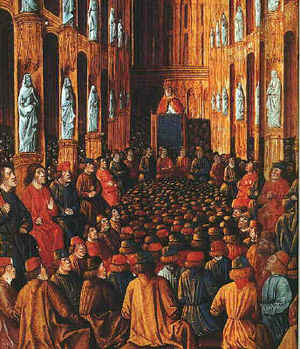

On November 27, 1095[57], Pope Urban II assembled a group of church leaders and nobles at Clermont, France. In an impassioned speech he described how the Turks had "seized more and more of the lands of the Christians . . . killed or captured many people, destroyed churches, and devastated the kingdom of God."[58] Urban's pleas fired his listeners with enthusiasm, and they spread the word throughout France. Those that joined the cause sewed a cross on their clothes and thus became crusaders, from the Latin word cruciata, "marked with a cross."

Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont. Illumination from the Livre des Passages d'Outre-mer, of c 1490 (Bibliothèque National)

The first crusaders—bands of undisciplined and untrained peasants—left for the Holy Land in 1096. As they traveled, they attacked all whom they considered enemies of Christ. They ravaged many Jewish communities. Solomon Bar Simson, a Jewish chronicler, described one attack:

“The

steppe-wolves . . . pillaged men, women, and infants, children and old people.

They pulled down the stairways and destroyed the houses, looting and plundering;

and they took the Torah Scroll, trampled it in the mud, and tore and burned

it.”[59]

Thousands of Jews died at the hands of these peasant crusaders.[60] As destructive as the peasants were, however, they were no match for trained warriors. Most died quickly in battle against the Turks.[61]

The forces led by French and Norman nobles had better luck. In three organized armies, they marched across Europe to Constantinople. Fearing the strength of the crusader armies, however, the Byzantine emperor, Alexius I, at first refused to admit them. “He dreaded their arrival,” wrote his daughter Anna Comnena, “knowing as he did their uncontrollable passion, their erratic character and . . . their greed for money.”[62] Eventually, however, Alexius let them pass through the city on their way to the Holy Land.

The journey was strenuous. Wearing wool and leather and heavy armor, the

crusaders suffered severely from the heat. Food and water ran short. As Fulcher

of Chartres, an eyewitness, recorded:

“The people for the love of God endured cold, heat, and torrents of rain. Their tents became old and torn and rotten from the continuous rains. . . . Many people had no cover but the sky. . . .

The elect were tried by the Lord and by such suffering were cleansed of their sins. . . . When they struggled against the pagans they labored for God. . . .

I feel that at the cost of suffering to the Christians He wills that the pagans shall be destroyed, they who have so many times foully trod underfoot all which belongs to God.”[63]

Despite the crusaders’ suffering, they took the city of Antioch, then marched on Jerusalem, which they quickly captured.[64] The inhabitants paid a fearful price in blood. One Muslim chronicler recorded that the crusaders killed more than 70,000 people.[65]

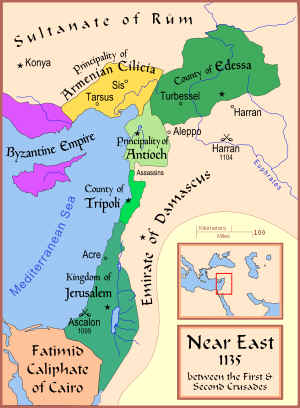

The victorious crusaders set up four small states in the newly captured Holy Land: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[66] They subdivided the land into fiefs controlled by lords and vassals.[67] A steady stream of pilgrims came to the Holy Land. European trade, with goods carried mostly in Italian ships, was brisk.[68] Catholicism was the official religion, but because Europeans were a minority, other religions were tolerated.[69] The crusader states ruled the Holy Land for almost a century.

The First Crusade had succeeded only because of disunity within the ranks of Islam. The fall of Jerusalem, however, proved as great a call to arms for Muslims as it had for Christians. By the middle of the 12th century, under the unifying leadership of the Ayyubid dynasty, the forces of Islam finally counterattacked, retaking the city of Edessa in 1144. In the face of this revival of Islamic power, a new call for troops went out in Christendom.[70] In 1147, a Second Crusade set out for the Holy Land. Unlike the first, the Second Crusade proved to be a miserable failure. After only two years, the armies of King Louis VII of France and the Holy Roman Emperor Conrad III returned home having achieved nothing but the loss of thousands of lives.

Then, in 1187, word

reached Europe that the Muslims had recaptured Jerusalem. Across Europe

knights sharpened their swords and spear points, and polished their chain mail

shirts. Richard I, the Lion Heart, of England, Philip Augustus of France, and the

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa each commanded an army headed to the

Holy Land. Once again, however, thanks to bad luck and disunity among the

leaders, the crusaders failed. Barbarossa drowned on his way to the

Holy Land.[71]

Philip and Richard quarreled,[72]

and Philip took his army home to seize English lands in France.[73]

Richard and his army fought on, but were unable to capture Jerusalem. In the

end, Richard had to settle for a truce that gave him control of a few coastal

towns and the right for Europeans to travel to Jerusalem on pilgrimage.[74]

Thus the Third Crusade left the crusaders only a small foothold in the Holy

Land.

Later Crusades.

Despite these failures, the crusading spirit died slowly. In 1202, for example, Pope Innocent III persuaded a group of French knights to embark on the Fourth Crusade to re-establish the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The crusaders did not have the money to pay for their travel, however. When merchants from Venice persuaded them to attack the Christian city of Zara, a commercial rival, as partial payment for their transportation,[75] the outraged pope excommunicated the entire army for attacking a Christian city. He soon lifted the ban, however, and the undeterred Venetians and the crusaders turned their attention to Constantinople. The Venetians hoped to take control of the entire eastern Mediterranean, which the Byzantines still dominated. In 1204 the crusaders breached the great walls of Constantinople. Savagely, they looted the city. Gold and treasure, even sacred icons and holy relics, flooded back into Western Europe.

The Fourth Crusade so intensified the distrust of Orthodox and Catholic Christians for one another that they never again joined forces to fight the Muslims. Later crusades in the Holy Land were also ineffective. The Children's Crusade of 1212 resulted only in many children being sold into slavery. By 1291 Muslims had captured the last Christian stronghold at Acre.

Although the major thrust of the crusading spirit had been directed

against Muslims in the Holy Land, the overflow of Christian zeal (and the desire

for booty) also found other targets. Spain became a major battleground, as

Christian knights fought to reconquer the peninsula from Spanish Muslims, or

Moors, as the Christian Europeans

called them. Spanish knights received aid from other Christian kingdoms. The

Moors received aid from Muslim Berber warriors from North Africa. By 1212,

Christian armies had driven the Moors from all but the southern coast and the

city of Granada. The Spanish crusade continued to arouse the nobler sentiments

of the crusading spirit. As late as 1376, for example, the heir to the English

throne, Edward the Black Prince, had his heart taken in a golden casket to Spain

after his death, where it was to be carried on crusade into battle against Islam

and only then buried. In this long struggle against the Moors, the Christian

kingdoms of Spain developed strong ties to the church. They also began to

struggle among themselves for power. Eventually, Castile and Aragon emerged as

the largest and most powerful of the Spanish kingdoms, dominating all the rest.

The Crusade Against Heresy

As the popes directed and unleashed the pent-up violence of European knighthood against the Muslim “infidels,” they also used it against the infidels within—Christians accused of heresy. Among those to feel the church’s wrath were the Albigensians, or Cathars. The Albigensians were a group of Christians in southern France who held distinctly un-Catholic views. At the heart of their doctrine was the belief that spirit was good and matter was evil. If matter was evil, they argued, Jesus could not be the incarnation of God—God made flesh—as the Roman Catholic Church taught.[76] Albigensian initiates, known as Perfects, sought to cleanse themselves of all fleshly desires, even those of eating and drinking. One of the holiest acts they could commit was to voluntarily release their souls through self-starvation.

Such doctrines not only clashed with more orthodox interpretations of

Christianity but also threatened to undermine the authority of both church and

state. Thus Pope Innocent III called for a crusade to stop the heresy. In 1208

an army marched in to kill the heretics.[77]

The sect had acquired a reputation in the region for sanctity, however, and was

supported by many nobles and local townsfolk. Some scholars have also suggested

that the defense of the heresy by local inhabitants represented a rejection of

outside authority. At any rate, the fighting continued for nearly 20 years,

destroying the population and the prosperity of one of France's richest regions.

It also gave rise to the Inquisition,

an official department of the church created to investigate and prosecute

charges of heresy.

The Crusade in the North

The end of the Albigensian crusade coincided with the beginning of a new eastward movement in northern Europe. This new movement brought together the passion of the crusades with the economic colonization of eastern Germany and Poland.

As German lords began to colonize northeastern Europe, they ran into tribes that were untouched by Christianity. The Teutonic Knights, an order of soldier monks, accepted the call of Andrew II, the king of Hungary, to fight against the pagans. After the pagans had been defeated, however, Andrew, fearing the knights’ power, expelled them from his kingdom.

In 1226 the order agreed to conquer the pagan inhabitants of Prussia, and bring them into the fold of Christendom. Soon, the entire order had shifted its headquarters from its place of origin, in Acre, and moved north of the Vistula River. There they established a fortified base at Torun. Over the next 50 years, the Teutonic Knights almost completely wiped out the pagan peoples of Prussia and established the whole region firmly within the Christian sphere. Growing in power, eventually the order came to rule most of the present-day Baltic States, with the exception of Lithuania.

As they grew in power, the Teutonic Knights incurred the wrath of the

Polish lords. Eventually the knights were defeated by a combination of Polish

and Lithuanian forces in the early 1400s. By the 1500s, the order had turned

their territories into secular dukedoms either under the Polish crown or the

Holy Roman Empire. In the meantime, however, they brought feudalism to eastern

Europe and the Baltic and fostered the growth of towns and the rise of trade.

Under their protection, for instance, the cities of northern Germany banded

together in what became known as the Hanseatic

League. The league eventually controlled most of the trade between Europe,

the Baltic, and Russia.

Results of the Crusades

Although all but one of the Crusades failed from a European standpoint, Europeans learned many important things from their contact with the Muslims. Europeans brought back new weapons, including the crossbow, a sophisticated bow and arrow held horizontally and fired by pulling a trigger. Since the crossbow could penetrate chain mail, knights developed heavier armor for protection.[1] The crusaders also learned to use carrier pigeons as messengers. From the Byzantines the Europeans learned new siege tactics[1] such as undermining walls and using catapults to hurl stones. In addition, they may have learned about gunpowder from the Muslims, who probably acquired their knowledge of this explosive from the Chinese.

In Europe the Crusades increased the power of kings and decreased the power of feudal lords. Many nobles either died fighting or spent their fortunes on the Crusades. Others sold political liberties to towns in order to raise money to go on a Crusade, thus decreasing their influence over the towns.[1] Kings imposed new taxes, and the increased wealth they provided (at the expense of many nobles) allowed kings to end the rebellions of vassals.[1]

The church too initially assumed more political power because of its leadership role in beginning the Crusades. However, some people began to resent the papal taxes that were raised to pay for the Crusades, particularly when most of the Crusades failed. In the long run, the failure of the Crusades may have undermined confidence in papal authority and contributed to a decline in papal power in the 1400s and 1500s.[1]

The Crusades had other important results. For example, some women had an opportunity to exert more power. With their husbands absent, many wives managed feudal estates or even governed kingdoms, as Eleanor of Aquitaine did while her son Richard was away on the Third Crusade.[1] Perhaps the most important impact of the Crusades, however, was on trade. As the first crusaders brought back spices, perfumes, and silks, a new demand for such luxuries swept through the European upper classes.[1] Demand for luxurious fabrics, beautiful carpets, and precious jewelry grew dramatically.[1] The popularity of these goods encouraged European artisans to make similar products.

Not least, the Crusades increased the power of Venice, whose fleets came to dominate the eastern trade. As merchants from northern ports tried to compete with the Italians, they soon looked even further beyond Europe’s borders. Although technically a failure, the Crusades, like the expansion of Europe to the northeast, demonstrated that Europe was at last beginning to come into its own. No longer on the defensive, European civilization had begun to grow outward once more.

Section 4 Review

Identify. Urban II, crusaders, Richard the Lion-Heart, Philip Augustus, Frederick Barbarosa, Inquisition, Hanseatic League.

Locate. Holy Land, Jerusalem, Venice, Poland, Vistula River, Lithuania.

1. Main Idea. Why did Europeans go on crusades?

2. Main Idea. How was the spirit of the crusades used against Christians?

3. Geography. How did the climate of the Holy Land affect the crusaders?

4. Writing to explain. Explain how some Europeans used the crusading spirit for economic gain.

5. Synthesizing. What did the crusaders ultimately accomplish? Why might the crusaders have been willing to kill people and invade far-away territory in the name of Christianity?