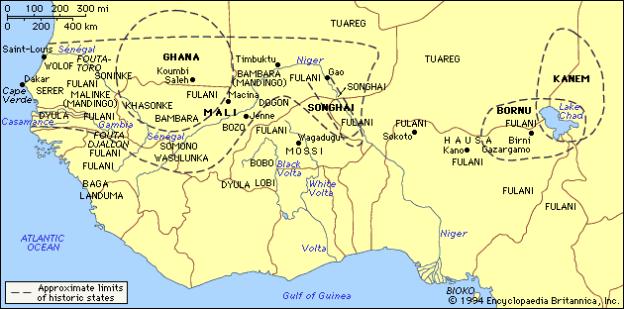

Chapter 13 Transformations in Asia and Africa on the Eve of European Overseas Expansion

While Muslim rulers were using the new weapons made possible by gunpowder to consolidate and expand their domains, in Africa too the new war technology brought changes. As early as the 1200s, the spread of Islam in the west and throughout North Africa had already contributed to the creation of large new empires. Throughout the 1600s Africans continued to improve on these states and to conquer others. To the east, the city-states of the Swahili coast gained from their contacts with the trade of the Indian Ocean, while further north, the Funj sultanate emerged in Nubia just as the Ottomans were conquering Egypt.

The Growth of the Swahili States

In the late 1100s, new waves of immigrants from Arabia and Persia began to settle in what they knew as the land of Zanj, along the east African coast. In the northern reaches of the coast, Persians and Arabs settled first in Mogadishu. From there they gradually moved south to Malindi, Mombasa, Pemba, Zanzibar, Mafia, and Kilwa. At Pemba, Mombasa, and Mafia they settled on the offshore islands as a precaution against attack from peoples further inland. With them they brought their own versions of Islamic civilization, which they soon spread to the African population with whom they freely intermingled and intermarried.

Further south, Indonesians had long been settling the great island of Madagascar, or Malagasy as it was known in their language, having followed the prevailing winds across the Indian Ocean. As all three groups began to intermingle, a new society emerged that combined African, Asian, and Islamic elements. The new society became known as Swahili, a reference to the language Kiswahili that developed along the coast out of a combination of Arabic elements with a Bantu language.

Taken from https://ancientafricah.wikispaces.com/file/view/CMA900.gif at http://ancientafricah.wikispaces.com/Swahili+Coastal+Trading+States

The Swahili of the east African coast were primarily merchants and traders. From the coastal cities they traded with African peoples further inland for gold and ivory, animal skins, and slaves. In exchange they offered fine pottery or porcelain, beads, spears, and other goods from India, China, and the emporia of the Middle East and Mediterranean world.

In fact, the cities of east Africa had long been in trade contact with the cities of Arabia, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, western India and all the other parts of the great Indian Ocean trading network. By the 900s, however, merchants from Oman and the Persian Gulf had established a dominant position in the region, trading as far south as Madagascar itself. Growing demands for the gold produced inland in these southern regions soon shifted the most important and profitable trade to the southern coastal city of Kilwa, which soon dominated the entire mid-coastal region from Sofala in the south to Pemba Island in the north.

The Muslim traveler ibn Battuta, who visited Kilwa in 1331, left a

description of his journey south from Mogadishu, including a stopover in

Mombasa:

“We spent a night on the island and then we set sail for Kilwa, the principal town on the coast, the greater part of whose inhabitants are Zanj of very black complexion. Their faces are scarred, like the Limiin of Janada. . . . Kilwa is one of the most beautiful and well-constructed towns in the world. The whole of it is elegantly built. The roofs are built with mangrove poles. There is very much rain. The people are engaged in a holy war, for their country lies beside that of pagan Zanj. The chief qualities are devotion and piety: they follow the Shafi’i rite.”[10]

The Swahili city-states achieved their greatest wealth and power in the 1300s and 1400s. Many of the cities produced specialized goods for export—Sofala for example produced cotton goods for the African interior trade, while Mombasa and Malindi were centers for the production of iron goods, especially tools. The most profitable trade items, however, came from the interior, especially gold and African ivory. Not even slaves brought such great returns, although many were shipped north to the Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Persian Gulf regions, as well as across the Indian Ocean to India, where local rulers used many African slave soldiers in their armies. Even Chinese aristocrats imported black slaves, using them primarily as household servants.

With the Swahili city-states to act as purchasing and shipping agents, the growing wealth of the overseas trade in African goods also stimulated developments in the interior. Gold, for example, came from the great city complex of Greater Zimbabwe, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers. The people of Greater Zimbabwe lived by raising crops, herding cattle, and working metals, including gold, which was to be found in the Zambezi watershed. They shipped the gold east to Sofala in exchange for goods from overseas. As part of the great Indian Ocean trading network, the cities of east African coast became the center of a dynamic cross-cultural trading culture.

The Empire of

Mali

While the growth of trade stimulated the east African

coastal cities, in West Africa both trade and the spread of Islam had an

even more dramatic effect. The collapse of Ghana had left several small

kingdoms constantly at war with one another. About 1200, the Mandinke

people of the kingdom of Kangaba, who had long been part of the Ghanaian

empire and were related, at least by language, to the Soninke of Ghana,

began to reunify the region. Kangaba had a large population and a thriving

agricultural economy. On this base they soon developed an empire even more

powerful than Ghana.

Sundiata. The first great Mandinke ruler to expand the kingdom was Sundiata. Sometime around 1230 Sundiata established his capital at the town of Niani, on the upper reaches of the Niger. Niani soon became a major center of trade. Organizing a powerful army, Sundiata then set out to conquer much of the old Ghanaian territory. He and his successors eventually brought all the major cities along the upper Niger into the new Mali Empire—Segou, Jenne, Timbuktu, and Gao. To the west they extended their sway all the way to the Senegal River and the Atlantic coast.

Like Ghana before it, the

Mali Empire was ruled by a warrior elite at the top, sustained by local

farmers and traders. Trade in fact was a royal monopoly and probably

accounted for the bulk of the rulers’ wealth. At the center of the

empire the emperors ruled personally, while appointing governors to rule

the provinces.

Mansa Musa. Mali reached the height of its power under Mansa (emperor) Musa in the early 1300s. With a territory nearly twice the size of Ghana, and controlling the north-south trans-Saharan trade, Mansa Musa became fabulously wealthy. To prevent potential rivals among the governors, in the early 1300s he began to appoint his own family members as provincial governors. Unlike his predecessors, however, Mansa Musa also became a devout Muslim. Although the bulk of the Mandinke remained true to their traditional animist religion, with the conversion of the emperor and the imperial court, Islamic practices became more and more influential in the empire.

In 1324, Mansa Musa

displayed both the wealth and power of his empire when he went on

pilgrimage to Mecca. His arrival in Cairo on his way to the Holy City

caused a sensation, as one of the Mamluk sultan’s officials later

recorded:

“Mansa Musa spread upon

Cairo the flood of his generosity: there was no person, officer of the

court, or holder of any office of the Sultanate who did not receive a sum

of gold from him. The people of Cairo earned incalculable sums from him,

whether by buying and selling or by gifts. So much gold was current in

Cairo that it ruined the value of money.”

Even 12 years after the visit, Cairo’s economy had

not entirely recovered from the inflation Mansa Musa’s gold had brought

on.

The spread of Islam. While the Mediterranean and Islamic world were thus introduced to the great Mali Empire, Mansa Musa also brought back considerable information from his trip that transformed Mali itself. He also began a building program, establishing new mosques in the larger cities of the empire. From these mosques, perhaps the most famous of which was in Timbuktu, Islam spread throughout the empire.

As Islam flourished under the patronage of the Malian rulers, Arab

and other Muslim traders and merchants began to travel even more widely in

the empire. Many married African women and thus carried Islam even further

into the local African populations. Such cross cultural developments and

intermingling soon gave Mali a reputation for both tolerance and justice.

In the mid-1300s, for example, the general character of the people

impressed Ibn Battuta:

“The Negroes possess some

admirable qualities. They are seldom unjust and have a greater abhorrence

of injustice than any other people. Their sultan shows no mercy to anyone

who is guilty of the least act of it. There is complete security in their

country. . . . They do not confiscate the property of any white man who

dies in their country, even if it be uncounted wealth. On the contrary,

they give it into the charge of some trustworthy person among the whites,

until the rightful heir takes possession of it. They are careful to

observe the hours of prayer . . . and in bringing up their children to

them. On Fridays, if a man does not go early to the mosque, he cannot find

a corner to pray in, on account of the crowd.”

The Songhay

Empire

By the beginning of the 1500s, the spread of Islam in West Africa had led to the rise of even larger empires than that of the Mandinke in Mali. From the city of Gao, a new Islamic dynasty emerged among the Songhai people to challenge the Malian emperors and eventually to take over and expand their empire. Under Muhammad Toure of Gao, in the late 1400s and early 1500s the Songhai absorbed the Mali Empire and extended its boundaries even further. Like Mansa Musa, Muhammad Toure too was a convert to Islam and he came to rely on advice and experts from the Islamic world in building his empire. He and his successors were largely successful because of their well-trained cavalry.

Under the Songhay Empire, the cities of West Africa continued to flourish. Timbuktu, for example, became a great center of Islamic learning with over a hundred Muslim religious schools. According to Leo Africanus, a Muslim traveler in Timbuktu around 1500 who later converted to Christianity, the emperor maintained so many “doctors, judges, priests, and other learned men” that one of the main commodities traded in the city was books: “And hitherto are brought diverse manuscripts or written books out of Barbarie the north African states, from Egypt to the Atlantic Ocean which are sold for more money than any other merchandise.”

There were many other items in the markets, however, for Timbuktu was a great commercial emporium. The Songhai were a wealthy people and European goods were in much demand as were goods from as far away as India and China. Such items were brought by a growing number of merchants—not only Arabs, but also Jews, Italians, and others from the Mediterranean and Middle East.

While trade was important, Songhay’s agricultural productivity provided the underpinning for the economy. Slaves were the most important element in this activity. Slaves working on the emperors’ farms and plantation produced rice, the main staple of the diet, as well as other products for the royal granaries scattered throughout the countryside. The slave trade itself was also an important factor in the economy. Muhammad Toure increased the slave supply considerably with his constant wars of expansion among the non-Muslim African peoples. Slaves were bought and sold in the market at Gao, with traders coming from North Africa to buy slaves for the markets in Cairo, Istanbul, Venice, and other Mediterranean slave markets.

Despite all this prosperity, however, the rulers of the empire also

had problems. They ruled many diverse peoples and they also had many

increasingly powerful neighbors. As their Tuareg, Fulani, Malinke, and

other subjects often fought among themselves, after Muhammad Toure the

empire began to experience a steady internal decline. In 1591, the

internal decay was compounded when an army from Morocco, armed with

firearms, overthrew the Songhai emperor’s troops in the battle of

Tondibi. Although the core of the empire continued to exist, this

essentially marked the collapse of Muhammad Toure’s great empire.

Despite its wealth, the Songhay Empire finally declined due to internal

decay and external enemies armed with guns.

Taken

from http://ctap295.ctaponline.org/~jboston/Student/materials.html

Kanem and

Bornu

Further east, the influence of Islam had penetrated even earlier than in the Mali and Songhai states. There too, ruling elites had used Islam as a means of rallying supporters and consolidating states. In the region around Lake Chad, for example, in 1085 a local ruler of the Kanem kingdom converted to Islam. Soon his successors were conquering the neighboring animist tribesmen. Although they forced them to pay tribute, however, the Kanem rulers allowed their new subjects to run their affairs much as they always had. The Kanem traded mostly slaves for horses and goods they could not make themselves.

As the Kanem Empire expanded, it soon made many enemies. By the late 1300s, these enemies were so numerous and violent that the Kanem ruler decided to move his own people to the nearby region of Bornu. There he simply started the whole process of state-building all over again. Eventually, under a later successor, Mai Ali, during the late 1400s the Bornu Empire began to expand. The empire reached its height under King Idris Aloma, who came to the throne in 1570. Like the Ottomans and the Safavids before him, Idris owed his success to the new gunpowder weapons, which he obtained from the Ottomans in Egypt and North Africa in exchange for slaves. In addition to arming his troops with firearms, he also maintained a large force of well-armed cavalry. With these advantages, Bornu soon became the most powerful state in the central Sudan region of Africa.