Chapter 16 The World in the Age of European Expansion 1492-1763

|

Section

2 |

|

Although Columbus had been heading for

Asia, instead he reached the Americas, which were soon linked

through trade and settlement to the rest of the world. In the

Americas, unlike Asia, the Spanish and Portuguese who followed

Columbus established huge land empires, based on plantation

economies, mining, and the use of Native American workers and slave

labor brought from Africa. As Native Americans, Africans, and

Europeans interacted, a new multicultural civilization began to

emerge. The Spanish in the Caribbean As

it became clear that the Americas were not the islands of Japan or

the mainland of either India or China, Spanish explorers looked for

other ways to make their fortunes in these new lands. In place of

trade, they turned to colonization. Columbus had established the

first colony to look for gold. When none was found, he soothed the

discouraged colonists by introducing the encomienda

system. Under this system, the colonists, or encomenderos, were granted land and the labor of a certain number of

Native Americans. The Native Americans had to farm the Spaniards'

land or work as servants. In return, the encomenderos

had to teach the Native Americans Christianity. This basic

pattern became the model for all subsequent Spanish settlements in

the Caribbean and on the mainland.

The encomienda proved to be a disaster for Native Americans. Apart from

the efforts to forcefully eradicate or utterly transform indigenous

cultures, the encomenderos

frequently overworked and mistreated Native American populations and

prevented them from growing their own food. Yet while Native

Americans frequently revolted against the Spanish in an effort to

defend themselves and their cultures, they proved no match for the

unseen invaders that the Europeans had unwittingly brought with

them. Diseases like smallpox, to which the peoples of Eurasia and

Africa had developed immunities over the centuries, ravaged the

Americans who had never been exposed to them. Spreading much faster

than the Europeans themselves, these diseases soon wiped out entire

settlements and led to a massive decline in the American

populations. The Conquest of the Aztec The

search for gold and other riches drew the Spanish from the Caribbean

to the mainland. In 1519 the ambitious conquistador,

or conqueror, Hernán Cortés, with a force of some 600 men and 16

horses, landed on the Mexican coast.[xxiv]

From the local inhabitants, they soon heard of a great and wealthy

civilization farther inland. As they advanced to find it, word of

their coming quickly reached the great city of Tenochtitlán,

capital of the Aztec Empire. Cortés and Moctezuma. The

Aztec emperor Moctezuma II received news of the Spaniards' arrival

with some anxiety. He believed that Cortés was the god Quetzalcoatl

coming to reclaim his throne. The strangers were covered with metal

and rode strange beasts, which the Native Americans had never seen.

Anxiously, Moctezuma sent rich gifts to Cortés. The sight of such

wealth only caused the Spaniards to march on Tenochtitlán even

faster. On the way, Cortés gained allies among the many enemies of

the Aztec. An Aztec chronicler found the Spanish force a fearsome

sight: “They

came in battle array, as conquerors, and the dust rose in whirlwinds

on the roads. Their spears glinted in the sun, and their pennons

[flags] fluttered like bats. They made a loud clamor as they

marched, for their coats of mail and their weapons clashed and

rattled. Some of them were dressed in glistening iron from head to

foot; they terrified everyone who saw them.”[xxv] Moctezuma

welcomed Cortés and gave him a palace to use inside the city. The

conquistador soon took the emperor prisoner, however, and demanded

gold. The battle for Mexico.

With Moctezuma imprisoned, the Spanish had seemingly taken the city

without a fight, but trouble soon broke out. In May 1520 Cortés

briefly left the city.[xxvi]

While he was gone, his men, horrified by the Aztec practice of human

sacrifice, attacked a religious festival, killing many of the

worshipers, including women and children.[xxvii]

Cortés returned in late June to find the outraged Aztec besieging

his men in Moctezuma’s palace. Hoping to calm them, Cortés

allowed the captive Moctezuma to speak to his people from the palace

rooftop. This only further enraged the Aztec, however. Moctezuma was

killed in the fight that ensued, though by whose hand is uncertain.

Deciding to retreat, Cortés and his men tried to sneak out

of the city on a dark, rainy night in late June.[xxviii]

A woman drawing water spied them, however, and gave the alarm,

"Our enemies are escaping."[xxix]

The Aztec attacked the fleeing soldiers, and both sides suffered

many casualties in what the Spanish later called La

Noche Triste, the Night of Sorrows.

The Aztec celebration of driving the Spaniards away was

short-lived. A smallpox epidemic swept through the battle-weary

population, killing thousands. In April 1521 the Spaniards returned,

supported by an army of Indian reinforcements, and laid siege to the

city.[xxx]

"Nothing can compare with the horrors of that siege and the

agonies of the starving," one Aztec later lamented.[xxxi]

After three months of resistance, the city fell on August 13, 1521.[xxxii] Consequences of the conquest.

Once in control, the conquistadors methodically looted the fallen

empire of its gold and silver. They also tried to suppress the Aztec

religion, as the use of human sacrifice revolted them. Even before

the fall of Tenochtitlán, Cortés himself had torn down the images

of the Aztec gods and replaced them with Christian statues, as he

described in a report home: “The

most important of these idols, and the ones in whom they have most

faith, I had taken from their places and thrown down the steps; and

I had those chapels where they were cleaned, for they were full of

the blood of sacrifices; and I had images of Our Lady and of other

saints put there, which caused . . .

[the] natives some sorrow.”[xxxiii] After

the conquest, the Spanish destroyed much of Tenochtitlán and built

their own capital—Mexico City—on its ruins. In the central

square, they tore down the great pyramid, and used its stones to

build a Christian cathedral.[xxxiv]

Thus, the Spanish gained most of present-day Mexico. From

their new base, they explored north, claiming much of what is now

the United States. To the south, they pushed into Central America.

Hearing rumors of yet another fabulously wealthy civilization

somewhere in the towering Andes Mountains, they also sent

expeditions into South America. There the Spanish soon discovered

the Inca Empire. The

Conquest of the Inca When

the Spanish arrived in the Americas, the huge Inca Empire extended

from present-day Ecuador to Chile. Though the empire looked strong,

its stability was crumbling. Smallpox spread to the Andes in the

late 1520s, killing one third to one half of the population in some

areas. Among the dead was the Inca emperor Huayna Capac.[xxxv]

A brutal civil war broke out between his sons—Atahualpa and Huáscar.

In 1531, Atahualpa emerged victorious.

Not long after his victory Atahualpa heard reports of a group

of foreigners in the empire. Francisco Pizarro and some 168 men[xxxvi]

had established a Spanish settlement on the empire's northern coast.

Despite their strange new weapons and horses, the new emperor did

not fear the Spaniards. Eventually, Atahualpa agreed to meet the

Spaniards in November 1532.[xxxvii]

At the meeting, a priest urged the emperor to convert to Catholicism

and handed him a Bible. When Atahualpa threw the book down in

disgust, on Pizarro’s order, Spanish soldiers seized the emperor

and killed most of his attendants.

Imprisoned by the Spanish, Atahualpa agreed to fill a room

with gold and another twice over with silver artifacts as a ransom.

He was as good as his word. Pizarro's share alone totaled 630 pounds

of gold and more than 1,000 pounds of silver.[xxxviii]

Despite Atahualpa’s show of good faith, in 1533 the Spanish

executed him. "With Atahualpa killed . . . and the clan of the

Inca already wiped out," an Inca official explained, "the

land was left without an overlord and with the tyrants in complete

possession."[xxxix]

Pizarro and his men headed south to Cuzco, the Inca capital.

There they defeated the remnants of Atahualpa's army and plundered

the wealthy city. Pizarro installed Manco Inca Yupanqui, the

16-year-old son of Huayna Capac, as puppet emperor. The Spaniards'

increasing demands for silver and gold turned the emperor against

them, however. Manco Inca’s son later recorded his father’s

reply to Spanish demands: “Ever

since you entered my country, there has been nothing . . . that has

been denied you, but instead any wealth I had you now possess,

whether in the form of children or adults, both male and female, to

serve you, or of lands, the best of which are now in your power.

What in the world do you need that I have not given you?”[xl]

Manco Inca soon raised a major rebellion against the

Spaniards that spread through much of the empire. At the head of a

large army, Manco Inca besieged Cuzco for 10 months. Unable to take

the city, in the end he retreated with many of his people into the

Andes Mountains where he established an independent state beyond

Spanish control. In 1572, however, the Spanish marched into the

mountains, defeated Tupac Amarú, the last Inca, and executed him.

The Spanish gradually extended their territory from their new

capital of Lima. They conquered Chile in the 1540s. In 1536 and

1538, an expedition from Spain founded the colonies of Buenos Aires

and Asunción. The Portuguese in Brazil Like

the Spanish, the Portuguese established a land empire in the

Americas. In 1500 a Portuguese navigator, Pedro Cabral, had been

blown off course while on his way to India. Sighting the coast of

Brazil, he claimed the territory for Portugal under the terms of the

Treaty of Tordesillas. Brazil's vast jungles and mighty rivers did

not easily yield the spices, gold, or silver that the Europeans

desired, however, and at first little was done about the new

territory. Not until 1534, after French raids threatened Brazilian

ships and settlements, did Portugal formalize its colonization of

Brazil.

King John III of Portugal granted huge tracts of land, called

captaincies, which

stretched westward from the coast. These captaincies were granted to

donataries, individuals

who agreed to finance colonization in exchange for political and

economic control of their new territory. Because of mismanagement

and vigorous resistance from Native Americans, only two of the

original captaincies prospered. Duarte Coelho Pereira, one of the

successful donataries, complained, "we are forced to conquer by

inches what Your Majesty granted by leagues."[xli]

In 1548 King John responded to such complaints by appointing

Tomé de Sousa as governor-general of Brazil. With him, the new

administrator brought colonists, bureaucrats, and Jesuit

missionaries. In 1549 Sousa founded Salvador, Brazil's first

capital.

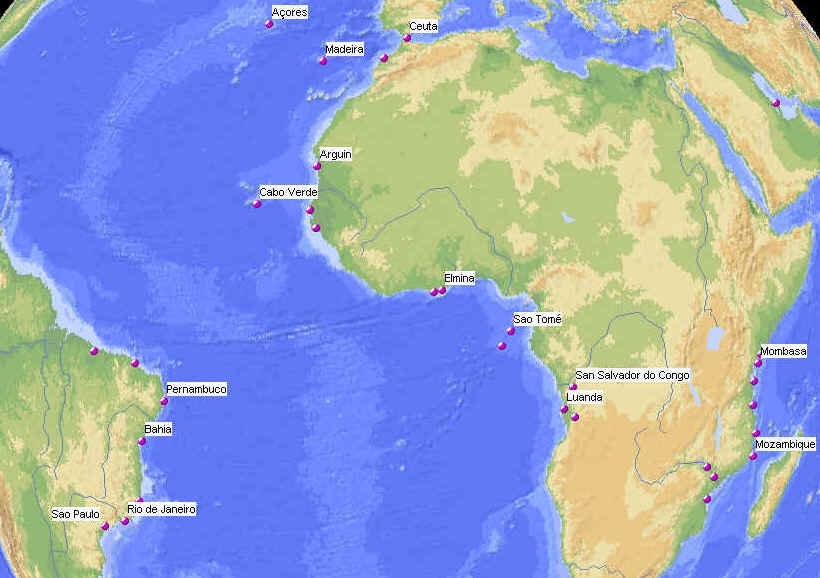

Map

of the Portuguese settlements in Africa and America around 1600.

Taken from http://www.colonialvoyage.com/pafrica.jpg Colonial Economy and Society The

conquistadors had won a vast empire for Spain that stretched from

the plains of North America to the Andes of South America. To govern

these geographically diverse and remote lands, the Spanish Crown

sent an army of bureaucrats to transform the conquistadors and the

conquered peoples into a settled society. Portugal controlled only

part of the eastern coast of South America but it faced a number of

challenges in governing its territory. Colonial government.

In Brazil, a governor-general appointed by the king was responsible

for both civil and military administration. The power of the

donataries limited his authority, however, as did the lack of

effective communications among the 14 different captaincies and

Portugal.

A more elaborate system emerged in Spanish America. The king

appointed a viceroy, or

governor, to oversee each viceroyalty, or large province. At first

there were only two viceroyalties: New Spain, in Mexico and Central

America; and New Castile, in Peru. In the mid-1700s two more were

added: New Granada, stretching from Panama to Ecuador and Venezuela;

and La Plata in Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia. Taken from http://www.bartleby.com/67/images/latina01.gif

Since all land in the new world theoretically belonged to the

king, the viceroys ruled as his personal representatives. However,

they ruled with the advice of a council, known as the audiencia,

whose members reported directly and privately to the king in Spain.

In addition, all senior officials were appointed from Spain, where

the king's Council of the Indies oversaw the entire American empire.

Thus, the Crown tried to maintain tight control over its colonial

administration.

Despite such safeguards, the system did not always work. In

Spanish America the encomenderos

wielded so much local power that they often ignored the viceroy's

orders. In the 1540s, for example, Pizarro’s brother Gonzalo

murdered Peru's first viceroy.

Later viceroys learned the practice of "I obey but I do not

execute," and simply ignored unpopular royal orders. The colonial economy.

Mines and agricultural estates provided most of the colonial

wealth. Gold mining, for example, fanned the growth of Rio de

Janeiro, which became the colonial capital of Brazil in 1763. Large,

self-sufficient farming estates, called haciendas

in Spanish America and fazendas

in Brazil, introduced European crops and animals to the Americas.

The Europeans largely re-created the life they had known in Europe.

In areas suitable for cattle they became ranchers, producing meat

and hides. Elsewhere they raised a variety of crops. Sugar

plantations prospered in Brazil, southern Mexico, and the Caribbean.

In addition to supplying local needs, the colonists exported goods

to Europe.

The biggest challenge the colonists faced was supplying labor

for the mines and the estates. As a result of disease and forced

labor, by the mid-1500s the Native American population had declined

in some areas by more than 90 percent.[xlii]

For example, in the viceroyalty of New Spain, covering present-day

Mexico, the southwestern United States, and much of Central America,

the Native American population declined from an estimated 11 to 25

million in 1492 to 1.25 million by 1625.[xliii]

As the Native Americans died, some conquistadors and clergymen

called for the Crown to protect these potential Christian converts.

One of the most outspoken of these early advocates was

Bartolomé de Las Casas. Las Casas had come to the Americas on

Columbus’s third voyage, and had been granted an encomienda. After witnessing the plight of the Native Americans,

however, he renounced his encomienda

and in 1512 became a priest. Thereafter he was tireless in his

efforts to protect the Native Americans. The Spanish monarchs shared

Las Casas’s concerns. Anxious for Catholic converts, they decreed

laws regulating the treatment of Native Americans. To replace Native

American labor, however, Las Casas and others suggested the use of

African slaves. Soon, thousands of Africans were being imported to

the Americas as slave labor. The development of colonial society.

The sometimes-tense coexistence of Africans, Europeans, and Native

Americans shaped the social order of the Americas. Society in Spain

and Portugal reflected the basic class divisions of Europe: nobles,

clergy, and commoners. In the Americas, wealth rather than noble

rank became the basis for high status.

As the Europeans moved into the Americas, they imposed their

own social order over the local peoples, one based not only on

wealth but also on race and even place of birth. A small group of peninsulares,

Spanish or Portuguese born in Europe, and creoles,

Europeans born in the colonies, ruled colonial society. The peninsulares

looked down on the creoles. Both the peninsulares

and the creoles looked down on the people of mixed race—the

mestizos, those of

Native American and European background, and mulattoes,

those of African and European ancestry. All of these people looked

down on Native Americans, Africans, and those of mixed Indian and

African parentage, the zambos. The multicultural nature of colonial society was reflected in its religious life. Catholic Christianity, the religion of the conquerors, spread rapidly. Catholic missionaries established schools, convents, and universities for the colonists. They also organized Native American settlements. Within several generations, most of Spanish and Portuguese America was Catholic.

Both Native Americans and African religious traditions

remained important, however. In the late 1500s, for example, Father

Bernandino de Sahagún wrote about his suspicion that Native

American adoration of the Virgin Mary disguised continuing worship

of the Aztec goddess Tonantzin: At [a small mountain they call Tepeyacac] they had a temple dedicated to the mother of the gods whom they called Tonantzin, which means Our Mother. There they performed many sacrifices in honor of this goddess. . . .

And now that a church of Our Lady of Guadalupe [the Virgin

Mary] is built there, they also call her Tonantzin. . . . It appears

to be a Satanic invention to cloak idolatry under the confusion of

this name, Tonantzin.[xliv] African

religious practices survived in many parts of the Americas in

dances, rituals, and religions such as Santeria, which mixed

African and Christian beliefs. Mercantilism and Its Consequences Both

the Spanish and the Portuguese tried to regulate the economies of

their colonies for their own national interests by practicing an

economic policy later called mercantilism.

Mercantilism became the dominant economic policy of Europe between

1500 and 1800. It was rooted in the belief that a country’s power

depended on its wealth in gold and silver. Since there was only a

limited supply of such precious metals, Europeans thought that a

country could only grow wealthy and powerful at the expense of other

countries. Consequently, European countries used their colonies to

provide raw materials and act as markets for their own goods, but

closed them off to other nations.

In keeping with this theory, Spain, for example, prohibited

its colonies from trading with other European countries. Every year

Spanish fleets carried wine, olive oil, furniture, and textiles to

the Americas, where they were exchanged for silver, gold, sugar,

dyes, and other products. The Spanish Crown also allowed Mexican

merchants to exchange silver for valuable Chinese silks and

porcelains and Asian spices from the Spanish Philippines.

Great silver strikes in Peru and Mexico enriched the Spanish

treasury for centuries. Although these riches at first made Spain

the wealthiest country in Europe, they also undermined the Spanish

economy. Instead of improving and expanding manufacturing and

agriculture in Spain, for example, the Spanish simply purchased what

they wanted or needed from other countries. The consequences of this

policy of neglect became evident when the steady flow of American

silver, combined with a rise in population that stimulated demand,

caused inflation throughout Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

Section 2 Review IDENTIFY and

explain the significance of the following: encomienda conquistador Hernán

Cortés Moctezuma La Noche Triste Francisco

Pizarro Manco

Inca Yupanqui Tupac

Amarú Pedro

Cabral captaincies donataries viceroy mercantilism LOCATE and explain the importance of the following: Lima Santiago Buenos

Aires Asunción Rio

de Janeiro. 1.

Main Idea How did the European

conquest of the Caribbean affect Native Americans? 2.

Main Idea What

groups composed Spanish American society? What was the status of

each? 3.

Geography: Place In the 1600s a

chronicler noted that, in contrast to the Spanish, the Portuguese in

Brazil were "content to scrape along the seaside like

crabs."[xlv]

What geographic factors do you think contributed to the captaincies

stretching inland from the coast? 4.

Writing to Inform

Imagine that you are a Spanish viceroy in the 1500s. Write a

letter to the king explaining why you cannot enforce laws reforming

the abuses of the encomienda system. 5.

Analyzing Using information from the

section, write a short essay analyzing (a) how the internal

political problems of the Aztec and Inca contributed to their

defeat; and (b) how their defeat allowed the Spanish, in two blows,

to win a huge landed empire. |