Chapter 17 European Revolutions of Society and State, 1714-1815

Section 5

After the radical Reign of Terror, France longed for a more stable form

of government. The French turned to the young, victorious general,

Napoleon Bonaparte to lead them. Within only a few short years, Napoleon

had declared France an empire with himself as emperor and had completely

reformed French government and society. He used his military genius to

expand the French Empire across Western Europe. Although the reforms of

the Revolution were carried by Napoleon throughout the continent, he

failed to unify Europe politically.

The Napoleonic Empire

A man of overwhelming ambition and domineering personality, Napoleon Bonaparte was one of the greatest military leaders of all time. Born in 1769[clxxxiii] on the French island of Corsica,[clxxxiv] Bonaparte trained at military schools in France, but it was the French Revolution that gave him the opportunity to rise in rank. Bonaparte’s genius lay in his ability to move troops rapidly and to mass forces at critical points on the battlefield. These techniques gave him a decided advantage over his opponents' older, slower tactics.

Bonaparte had gained experience and fame in the war with Austria. By 1797[clxxxv] he had begun to expand France by seizing northern Italy from the Austrians. The next year, he launched an expedition to Egypt, hoping to establish a French colony and to disrupt Britain's trade route to India. However, Horatio Nelson,[clxxxvi] the British naval leader, cut off the French general and his troops in Egypt. After a year of fierce fighting Bonaparte finally left his army stranded and returned to France.

He found the country in a state of crisis. Britain, Austria, and Russia had formed a Second Coalition against the French republic. Internal discontent was also reaching a breaking point. As the Directory fell in 1799, Bonaparte restored order—then took control of the government himself.[clxxxvii] Reviving old Roman republican titles, he established the Consulate, with himself as First Consul.

By 1804[clxxxviii]

the First Consul’s ambition had grown even more. After conducting a

public referendum in which the French people “voted” to declare

France an empire, Bonaparte assumed the title of Emperor as Napoleon I.

He was crowned in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. Napoleon even

summoned the pope to preside over the coronation – though at the last

moment, in a symbolic gesture that shocked both the onlookers and the

rest of Europe, he abruptly took the crown from the pope’s hands and

placed it upon his own head.

Napoleon Crowning

himself emperor. Taken from http://teachers.ausd.net/antilla/crown1.jpg

Napoleon's reforms in France. Many people welcomed Napoleon's dictatorship because it promised stability. Although Napoleon supported the changes of the Revolution, he firmly believed that people must strictly obey orders given by a leader. He reorganized and centralized the administration of France to give himself unlimited power.

Under the emperor’s direction, scholars revised and reorganized all French law into a system known as the Napoleonic Code. Napoleon established a central financial institution, the Bank of France, and his government put into place the public school system that the National Convention had planned years before. The school system included elementary schools, high schools, universities, and technical schools. In addition, Napoleon established a meritocracy in French government. People advanced in government service based upon their merit and abilities, not on wealth or heredity.

Napoleon also eased the strains between the French government and the Roman Catholic Church that had developed because of the Revolution. In 1801[clxxxix] he reached an agreement with the pope. The Concordat, as it was called, acknowledged Catholicism as the religion of most French citizens, but it did not abolish the religious toleration guaranteed by the Declaration of the Rights of Man. The church also gave up claims to the property the government had seized during the Revolution.

On the battlefield Napoleon destroyed the Second Coalition against France and won more territory in Italy and along the Rhine River.[cxc] By the time of his coronation as emperor, Napoleon appeared to have kept his promises to win peace by military victory, achieve steady government, and create economic prosperity.

The Napoleonic Wars

Napoleon's growing power posed a threat to other European nations. When it became clear that Napoleon's ambition threatened British commerce, Great Britain became Napoleon's most determined enemy. After a brief period of peace,[cxci] Britain renewed the war and formed the Third Coalition against France with Austria, Russia, and Sweden in 1805.[cxcii] Napoleon planned to crush the British by defeating their navy and invading England. His plans were thwarted, however, when Admiral Nelson sank nearly half the combined French and Spanish fleets near Trafalgar[cxciii] off the southern Spanish coast. The Battle of Trafalgar[cxciv] established British naval supremacy for the next century.

The Continental System. Napoleon had one more weapon against the British—damaging their trade. Napoleon despised the British, calling them "a nation of shopkeepers." He believed that if the British lost their foreign trade, they would be willing to make peace on his terms. He declared the British Isles to be in a state of blockade and forbade not only everyone in the French Empire but also all his “allies” from carrying on commerce and correspondence with Britain.[cxcv] This blockade was called the Continental System because Napoleon controlled so much of the continent of Europe. The British responded with a blockade of their own. They ordered the ships of neutral nations to stop at British ports to get a license before trading with France or its allies. This conflict placed neutral nations in an awkward position. If they disregarded the British order, the British might capture their ships. If they obeyed, the French might seize their ships.

The Continental System and the British blockade hit the United States particularly hard, for it depended heavily on trade with both Britain and the continent. This conflict, in part, led to the War of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States. Although the British blockade hurt France, Napoleon continued to win battles against the Third Coalition. In December 1805[cxcvi] the French emperor smashed the combined forces of Russia and Austria at Austerlitz[cxcvii] north of Vienna and the Third Coalition soon collapsed.

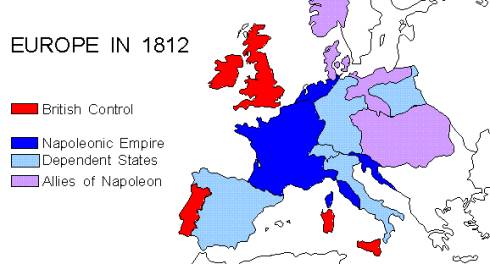

Napoleonic reforms in Europe. By 1808[cxcviii]

Napoleon completely dominated Europe. The French Empire included

Belgium, the Netherlands, and portions of Italy. He dismantled the Holy

Roman Empire and replaced it with the Confederation of the Rhine, a

league of German states with Napoleon himself as protector. The last

Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor proclaimed himself instead the emperor of

the new Austro-Hungarian Empire, and agreed too an alliance with

Napoleon.

Taken

from http://www.historyofwar.org/Maps/europe1812.gif

Wherever

the French army went, it put the Napoleonic Code into effect, abolished

feudalism and serfdom, and introduced its modern military techniques.

Without intending to, the French also helped awaken in the people they

conquered a spirit of nationalism,

recognition that they shared a common language, culture, and history.

Feelings of nationalism appeared among conquered peoples, especially

among Germans. One German poet wrote:

“What is the German's fatherland?

Now name at last that mighty land!

'Where’er resounds the German tongue,

Where’er its hymns to God are sung!'

That is the land,

Brave German, that thy fatherland!”[cxcix]

Napoleon ruled Europe, but time worked on the side of his

enemies. The coalition re-formed and his opponents' armies grew

stronger. The generals who opposed him in the field copied his methods

of moving and massing troops rapidly.

Napoleon's Downfall

In 1812[cc]

Russia began making plans for war against France. After learning about

this plan in the spring of 1812,[cci]

Napoleon launched a massive invasion of Russia. The campaign was doomed

from the start. Napoleon's army was immense, more than half a million

men. The army was drawn largely from his “allies,” however, and

perhaps fewer than half the troops were French. In addition, the long

distances and shortages of food weakened the army in Russia.

Defeat at Moscow. Napoleon believed that once he had captured

Moscow, the Russians would ask for peace. When his army arrived in the

city, however, Moscow was in flames. An observer noted, "Orders had

been given by the [Russian] governor of the city and the police that the

whole city should be burned during the night."[ccii]

“Moscow Burning”. Taken from http://www.napoleonexhibit.com/img/gallery/PJC03030_066.jpg

As winter approached,

Napoleon began withdrawing his troops from Moscow, but the bitter winter

weather and the pursuing Russian troops decimated Napoleon’s once

proud army. Only about 100,000 men survived. One soldier described the

retreat across Russia:

"The carriages, drawn by tired and

underfed horses, were traveling fourteen and fifteen hours of the

twenty-four. . . . Having

left Moscow with us, . . . [the carriages] had had to take up the men

wounded, . . . They were

put on the top-seats of the carts. . . . At the least jolt those who

were most insecurely placed fell; the drivers took no care. The driver

following . . . for fear of stopping and losing his place . . . would

drive pitilessly on over the body of the wretch who had fallen."[cciii]

As Napoleon once again abandoned his struggling men and returned to France to raise more troops, Prussia and Austria seized the chance to form a new coalition with Russia. The coalition attacked and defeated Napoleon at Leipzig[cciv] in Germany. Meanwhile, in the southwest, British forces based in Portugal defeated Napoleon’s Spanish allies and swept north over the Pyrenees. With his enemies closing in, Napoleon gathered his forces to fight one last campaign northeast of Paris in the spring of 1814.[ccv] Allied armies of Britain, Austria, Russia, and Prussia soundly defeated him. In April[ccvi] Napoleon abdicated and went into exile on the island of Elba,[ccvii] off the Italian coast.

After 25 years of changing governments and near-constant warfare,

France was exhausted. Napoleon's former foreign minister,

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand,[ccviii]

took charge of restoring the Bourbon[ccix]

dynasty to the throne. Louis XVIII, a brother of the beheaded Louis XVI,

issued a constitution to placate the French people. As he soon reverted

to the old authoritarian ways of his family, however, many feared that

the Old Regime was re-establishing itself and discontent quickly grew in

France.

The last Hundred Days. In March of 1815[ccx] Napoleon left his exile in Elba. Landing on the French coast near Marseilles with a small force, he marched toward Paris. Along the way throngs of supporters welcomed him. Louis XVIII sent French army units to stop him – instead they joined him. As Napoleon entered Paris in triumph, Louis fled once again into exile. So began Napoleon’s final effort to restore the empire, a period known as the Hundred Days.

The allies who had defeated the emperor the previous year rapidly

massed their troops together in Belgium. Near the tiny village of

Waterloo,[ccxi]

the British commander, the Duke of Wellington, with the crucial aid of

Prussian forces, soundly crushed Napoleon's army, thus bringing the

Hundred Days to an end. As the Bourbons returned to power once more, the

British exiled Napoleon to the South Atlantic island of St. Helena,[ccxii]

where he finally died in 1821.[ccxiii]

Section 5 Review

IDENTIFY and explain the significance of the following:

Admiral Horatio Nelson

Consulate

Napoleonic Code

meritocracy

Concordat

Continental System

nationalism

Charles-Maurice Talleyrand

Louis XVIII

the Duke of Wellington

Hundred Days

LOCATE and explain the importance of the following:

Trafalgar

Austerlitz

Leipzig

Elba

Waterloo

St. Helena

1.

Main Idea How

did Napoleon strengthen Franc’s power?

2.

Main Idea

How was Napoleon able to dominate Europe?

3. Geography: Place How did Russia's geography affect the outcome of Napoleon's invasion?

4. Synthesizing How did Napoleon reform French society? Consider the following in your answer: (a) the Napoleonic Code; (b) the Concordat; (c) meritocracy; and (d) national identity.

Chapter 17 Review

REVIEWING TERMS

From the following list, choose the term that correctly matches the definition.

philosophes

National Assembly

Navigation Acts

Declaration of Independence

Continental System

natural law

1. Napoleon's strategy to destroy Britain's commerce by controlling all trade in ports on the European continent

2. group composed of delegates of the Third Estate and some delegates of the First Estate who planned to write a constitution for France

3. thinkers in the Enlightenment

4. idea that a system of laws governs all aspects of the universe

5.

document signed on July 4, 1776, declaring the British colonies of

North America free from British rule

REVIEWING CHRONOLOGY

List the following

events in their correct chronological order.

1. Citizens of Paris storm the fortress of the Bastille.

2. The Seven Years' War breaks out.

3. The Treaty of Paris is signed, ending the American War of Independence.

4. Angry colonists throw a shipment of British tea into Boston Harbor.

5. The forces of Napoleon are defeated at the battle of Waterloo.

UNDERSTANDING THE MAIN IDEA

1. How did Napoleon transform European society?

2. What was the Enlightenment?

3. Why can the Seven Years' War be called a "global war"?

4. What factors contributed to the British colonies of North America winning their independence?

5. How did the Enlightenment influence the American Revolution and the French Revolution?

6. What were the causes of the French Revolution?

THINKING CRITICALLY

1. Comparing and Contrasting How was the French Revolution similar to the American Revolution? How were the outcomes of the two events different? What accounted for the difference?

2. Distinguishing Fact from Opinion Why is the following statement only partially correct? Napoleon's conquest of Europe liberated many subject peoples from oppression.

Through Others' Eyes: A Syrian Response to the French Revolution

While much of Europe was in turmoil from the French Revolution, the Ottoman Empire was mostly untroubled by the Christians' problems.[ccxiv] As can be seen from historical accounts of the time, many Muslims showed little concern or even interest in what occurred in France.[ccxv] A Syrian historian, Niqula el-Turk, wrote this brief account of the revolution in his history of Egypt:

"We begin with the history of the appearance of the French Republic in the world after they killed their king and this at the beginning of the year 1792 of the Christian era corresponding to the year 1207 of the Islamic hijra. In this year the people of the kingdom of France rose up in their entirety against the king and the princes and the nobles, demanding a new order and a fresh dispensation, against the existing order which had been in the time of the king. They claimed and confirmed that the exclusive power of the king had caused great destruction in this kingdom, and that the princes and the nobles were enjoying all the good things of this kingdom while the rest of its people were in misery and abasement [degradation]. Because of this they all rose up with one voice and said: 'We shall have no rest save by the abdication of the king and the establishment of a Republic.' And there was a great day in the city of Paris and the king and the rest of the people of his government, princes and nobles, were afraid, and the people came to the king and informed him of their purpose. . . . [ccxvi]

Literature through Time

Grimm's Fairy Tales

When the French were

driven out of Germany in 1813, many Germans looked for ways to give the

German people a sense of unity. Under French occupation, the German

states had been divided into a number of government districts and free

cities in order to keep the Germans from uniting against the occupying

forces. Some intellectuals hoped to restore pride in the German heritage

by encouraging Germans to rediscover their literary past. Even during

the French occupation, two brothers, Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, began

gathering old legends and folk tales from many parts of Germany.[ccxvii] They published the

first volume of Grimm's Fairy

Tales in 1823, and continued to update the collection throughout

their lives.[ccxviii] The tales themselves

often are versions of stories handed down through many generations. Grimm's

Fairy Tales have become famous all over the world. You probably

recognize some, such as "Red Riding Hood," "Hansel and

Grettel," and "Rapunzel." Below is one of the shorter

fairy tales, "The Star-Money."

"There was once upon a time a

little girl whose father and mother were dead, and she was so poor that

she no longer had a room to live in, or bed to sleep in, and at last she

had nothing else but the clothes she was wearing and a little bit of

bread in her hand which some charitable soul had given her. She was good

and pious, however. And as she was thus forsaken by all the world, she

went forth into the open country, trusting in the good God. Then a poor

man met her, who said: "Ah, give me something to eat, I am so

hungry!" She handed him the whole of her piece of bread, and said:

"May God bless you," and went onwards. Then came a child who

moaned and said: "My head is so cold, give me something to cover it

with." So she took off her hood and gave it to him; and when she

had walked a little further, she met another child who had no jacket and

was frozen with cold. Then she gave it her own; and a little further on

one begged for a frock and she gave away that also. At length she got

into a forest and it had already become dark, and there came yet another

child, and asked for a shirt, and the good little girl thought to

herself: "It is a dark night and no one sees you, you can very well

give your shirt away," and took it off, and gave away that also.

And as she so stood, and had not one single thing left, suddenly some

stars from heaven fell down and they were nothing else but hard smooth

pieces of money, and although she had just given her shirt away, she had

a new one which was of the very finest linen. Then she put the money

into it, and was rich all the days of her life."[ccxix]

Understanding Literature

Why might many Germans have enjoyed reading stories handed down from German folklore?

![]()

[i]WH p. 400.

[ii]WH p. 401.

[iii]CHW p. 754.

[iv]CHW p. 754.

[v]CHW p. 742

[vi]CHW p. 742

[vii](11)

[viii](11)

[ix](11)

[x]WH pp. 961--62.

[xi]Raymond Birn. Crisis, Absolutism, Revolution: Europe 1648-1789 (Fort Worth: HBJ, 1992): 304.

[xii](10)

[xiii](10)

[xiv]Birn, 304.

[xv](10)

[xvi]Birn, 304

[xvii](11)

[xviii]Raymond Phineas Stearns. Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day. (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961):328.

[xix]Stanley Chodorow, et al. The Mainstream of Civilization, Sixth Edition (Fort Worth: The Harcourt Press, 1994): 568.

[xx]Chodorow, 329.

[xxi](1)

[xxii]CHW pp. 632--33.

[xxiii](1) p. 573.

[xxiv](11)

[xxv](11)

[xxvi]Birn, 292, and (11).

[xxvii]Birn, 293.

[xxviii]Birn, 293.

[xxix]"Frederick William I," in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 277.

[xxx]H.W. Kock, A History of Prussia, p. 100.

[xxxi](11)

[xxxii]Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day, Second Edition (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 280.

[xxxiii]HW Koch, A History of Prussia (London: Longman, 1978): 110.

[xxxiv](11)

[xxxv](10)

[xxxvi]Koch, 110.

[xxxvii](11)

[xxxviii]Birn, 296

[xxxix]WH p. 16.

[xl]Birn, 298

[xli]CHW p. 749.

[xlii]WH p. 961.

[xliii]WH p. 962.

[xliv](11)

[xlv](10)

[xlvi]Webster's Biographical Dictionary, 1068.

[xlvii](11)

[xlviii](10)

[xlix](10)

[l]Robert Clive, "Report on the Battle of Plassey" in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 324.

[li]Christopher Hill, The Pelican Economic History of Britain, Volume 2: 1530-1780, Reformation to Industrial Revolution (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1969): 232.

[lii](11)

[liii]Richard Middleton, The Bells of Victory: The Pitt-Newcastle Ministry and the Conduct of the Seven Years' War, 1757-1762 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985): 18.

[liv]Richard Middleton, The Bells of Victory, p. 145.

[lv]Hill, 232.

[lvi]WH p. 821.

[lvii](10)

[lviii]Birn, 332.

[lix]WH p. 821.

[lx]Birn, 335.

[lxi]Birn, 333.

[lxii]Birn, 333.

[lxiii](11)

[lxiv](11)

[lxv]Voltaire, Candide, Zadig and Selected Stories. trans. Donald M. Frame. (New York: New American Library, 1981): 78.

[lxvi]"The Enlightenment was a widely disseminated attitude of mind rather than...a specifically literary or philosophical movement." Norman Hampson, "The Enlightenment in France" in Roy Porter and Mikulá˘s Teich, The Enlightenment in National Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981): 43. Most sources refer to the Enlightenment as a movement, but it wasn't an organized movement as such. Should we refer to it as a movement? A change in worldview?

[lxvii]CHW p. 681.

[lxviii]CHW p. 690.

[lxix]Hampson, 42.

[lxx]Stearns, 200.

[lxxi](11)

[lxxii]Birn 239. The number is only "the hundred-plus contributors" in Sara Ellen Procious Malueg, "Women and the Encyclopédie" in Samia I. Spencer, ed. French Women and the Age of Enlightenment (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984): 261.

[lxxiii](11)

[lxxiv](11)

[lxxv]Fox-Genovese, 260.

[lxxvi]CHW pp. 701--2

[lxxvii](11)

[lxxviii]Owen Chadwick, "The Italian Enlightenment" in Roy Porter and Mikulá˘s Teich, eds., The Enlightenment in National Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981): 97.

[lxxix](11)

[lxxx]Ernst Wangermann, "Reform Catholicism and Political Radicalism in the Austrian Enlightenment" in Roy Porter and Mikulá˘s Teich, eds., The Enlightenment in National Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981): 135.

[lxxxi]Joachim Whaley, "The Protestant Enlightenment in Germany" in Roy Porter and Mikulá˘s Teich, eds., The Enlightenment in National Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981): 109.

[lxxxii]CHW pp. 702--3

[lxxxiii](11)

[lxxxiv](11)

[lxxxv]Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws (Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952): 3.

[lxxxvi](11)

[lxxxvii]Hampson, 49.

[lxxxviii]Birn, 260.

[lxxxix](11)

[xc](11)

[xci]TRY TO WORK IN THE FOLLOWING: Colbert quotes on page 75, in Heilbroner, The Making of Economic Society, 4th edition.

[xcii](11)

[xciii](11)

[xciv]Wollstonecraft, 8.

[xcv]Wollstonecraft, 10.

[xcvi](11)

[xcvii]Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Miriam Kramnick, ed. (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1975): 121.

[xcviii](11)

[xcix](11)

[c]Wollstonecraft, 17.

[ci]Anderson, vol. 2, 124.

[cii](11)

[ciii](11)

[civ]Bonnie S. Anderson and Judith P. Zinsser, A History of Their Own: Women in Europe from Prehistory to the Present, Volume II (New York: Harper & Row, 1988): 109.

[cv](11)

[cvi]Anderson, vol. 2, 109.

[cvii]Anderson, vol. 2, 115.

[cviii]Anderson, vol. 2, 114.

[cix]Pageant of Europe, p. 313.

[cx]WH p. 933.

[cxi]Catherine the Great, "Instructions to the Commissioners for Composing a New Code of Laws," in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 315.

[cxii]"Catherine the Great and the Enlightenment" in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 313.

[cxiii]Birn, 319.

[cxiv]Birn, 315.

[cxv]Frederick the Great, "Essay on Forms of Government and the Duties of Sovereigns" in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 289.

[cxvi]Birn, 314.

[cxvii](11)

[cxviii]Birn, 321.

[cxix]Birn, 257.

[cxx]Joseph II to Von Swieten (1787) in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 293.

[cxxi]Birn, 322.

[cxxii]WH p. 1001.

[cxxiii](11)

[cxxiv]John Dickinson, "Letters from a Farmer, 1767-8" in Richard Hofstadter, Great Issues in American History: From the Revolution to the Civil War, 1765-1865 (New York: Vintage Books, 1958): 24.

[cxxv]WH p. 119.

[cxxvi]WH p. 267.

[cxxvii]WH p. 36.

[cxxviii](1) p. 560.

[cxxix](11)

[cxxx]Thomas Paine, Common Sense in Richard Hofstadter, Great Issues in American History: From the Revolution to the Civil War, 1765-1865 (New York: Vintage Books, 1958): 56. (Melissa's copy)

[cxxxi](1) p. 560.

[cxxxii](11)

[cxxxiii]Todd/Curti, 119.

[cxxxiv]Thomas Jefferson, "The Declaration of Independence" in Richard Hofstadter, Great Issues in American History: From the Revolution to the Civil War, 1765-1865 (New York: Vintage Books, 1958): 70.

[cxxxv](11)

[cxxxvi]Hibbert, 335.

[cxxxvii]Hibbert, 335.

[cxxxviii]WH pp. 36--37.

[cxxxix](10)

[cxl]WH p. 36.

[cxli]WH p. 37.

[cxlii]WH p. 37.

[cxliii]WH p. 60.

[cxliv]WH p. 60.

[cxlv]WH p. 265.

[cxlvi]Middlekauff, 622 (May 14, 1787) and 648 (Sept 17, 1787).

[cxlvii]WH p. 265.

[cxlviii]WH p. 265.

[cxlix]WH p. 400.

[cl]WH p. 400.

[cli]Encyclopedia Britanica Vol. 7, p. 647.

[clii]CHW p. 763.

[cliii](11)

[cliv](11)

[clv]CHW p. 763.

[clvi]WH p. 400.

[clvii](11)

[clviii]Hibbert, French Revolution, 47.

[clix](11)

[clx]WH p. 400.

[clxi]WH p. 400.

[clxii]A History of Their Own Vol. 2, p. 351.

[clxiii]Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989): 498.

[clxiv]Schama, 498.

[clxv]Schama, 498.

[clxvi]WH p. 400.

[clxvii](11)

[clxviii](11)

[clxix](11)

[clxx]WH p. 401.

[clxxi]CHW p. 768.

[clxxii]WH p. 401.

[clxxiii]WH p. 401.

[clxxiv]"Levée en Masse" in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 401. (need to verify---we no longer have this book.)

[clxxv](10)

[clxxvi]"Law of Suspects," in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 402.

[clxxvii]It would be a good idea to have a reading selection in the support materials on the Reign of Terror.

[clxxviii](11)

[clxxix](11)

[clxxx]WH p. 402.

[clxxxi]WH p. 402.

[clxxxii](13) Vol 7, p. 659.

[clxxxiii](11)

[clxxxiv](10)

[clxxxv](1) p. 635.

[clxxxvi](11)

[clxxxvii]CHW p. 764.

[clxxxviii]WH p. 752.

[clxxxix]WH p. 751.

[cxc](10)

[cxci]WH p. 752.

[cxcii]WH p. 752.

[cxciii](10)

[cxciv]WH p. 752.

[cxcv]Napoleon, "Berlin Decree" in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 431.

[cxcvi]WH p. 752.

[cxcvii](10)

[cxcviii]Times Atlas of World History, p. 205.

[cxcix]Ernst Moritz Arndt, "What is the German's Fatherland?" in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 440.

[cc](1) p. 645.

[cci]WH p. 753.

[ccii]General de Caulaincourt, "Memoirs" in Raymond Phineas Stearns, Pageant of Europe: Sources and Selections from the Renaissance to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961): 437.

[cciii]Pageant of Europe, pp. 437--38.

[cciv](10)

[ccv]WH p. 753.

[ccvi]WH p. 753.

[ccvii](10)

[ccviii](11)

[ccix](11)

[ccx]WH p. 753.

[ccxi](10)

[ccxii](10)

[ccxiii]WH p. 751.

[ccxiv]Bernard Lewis, The Muslim Discovery of Europe (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1982), 53.

[ccxv]Ibid., 54.

[ccxvi]Ibid.

[ccxvii] Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol 90, p. 102.

[ccxviii] Ibid.

[ccxix] Grimm's Fairy Tales, pp. 652--654.