Chapter 1 Before Civilization

HUMANITY

AND THE ENVIRONMENT

The search for water and food

was probably the primary motive for the spread of these early human beings, as

it had been for their hominid predecessors. For, like other species, early human

beings lived at the whim of nature. They followed their food and water supplies,

not yet having learned how to control them, perhaps not knowing yet any need to

control them.

These early humans lived by hunting

and gathering the food they needed: small animals, insects, roots, berries,

nuts, seeds, edible plants. Such food sources of course were heavily dependent

upon the types and amount of water resources available as well as the fertility

of the soil. As early humans learned

to cooperate and coordinate their activities, they also became capable hunters

of larger animals. This increased the levels of protein in their diets, thereby

contributing to their further physical development. Since they constantly moved

from place to place in search of these foodstuffs, never settling anywhere for

very long, today we call these people nomads.

The most important element of the environment in these early stages of

human development was undoubtedly the climate. While in geologic time the most

important changes have been tied to the splitting apart of the continents, such

events have usually moved far too slowly to interfere with the long-term

survival or development of a species. Changing patterns in the general climate

and weather, however, have been much faster, and have consequently affected

human beings much more directly and suddenly - forcing them to adapt culturally

rather than biologically in order to survive. The reasons for such rapid periods

of climate change have varied. Some have indeed been functions of the processes

of continental drift in the form of on-going volcanic processes of the planet.

Perhaps even more spectacular have been the consequences of occasional

interplanetary collisions – as asteroids and comets have struck the earth with

devastating consequences for the planet’s life forms. Perhaps the steadiest

changes have come from the slight wobble in the planet’s orbit about the sun

– a wobble that has contributed to cyclical changes in the relative warmth and

cold of planetary climate zones, marked by periodic advance and retreat of polar

ice.

For most of human history the spread of human populations, perhaps even

the evolution of the species, has been largely determined by the Ice Ages. When

human beings first appeared on the planet, the earth was experiencing one of its

colder phases of climate. The only really warm places were Central and South

America, Africa, and parts of southeastern Asia. Between 2.5 million and 1

million years ago, the climate grew even colder, so cold that in Northern

Eurasia and Canada the snow that fell in winter did not thaw in the summers.

Soon, huge sheets of ice formed in these northern regions and began to move

slowly south.

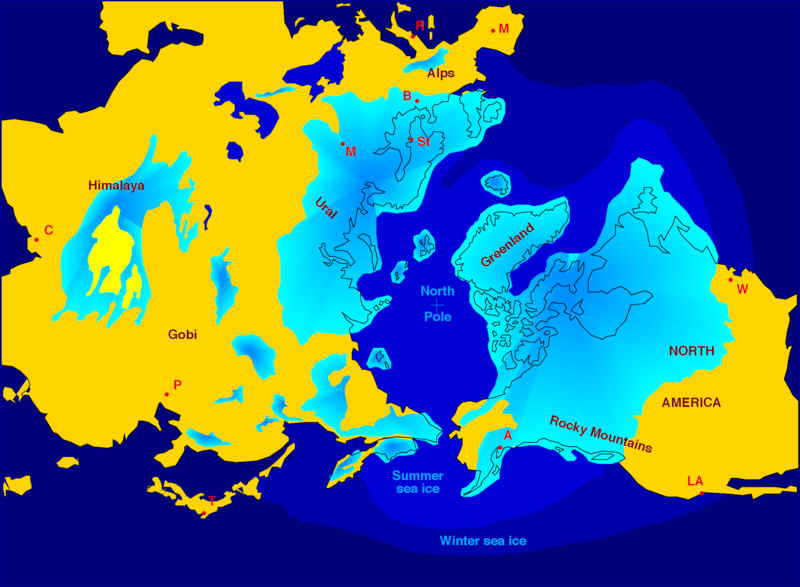

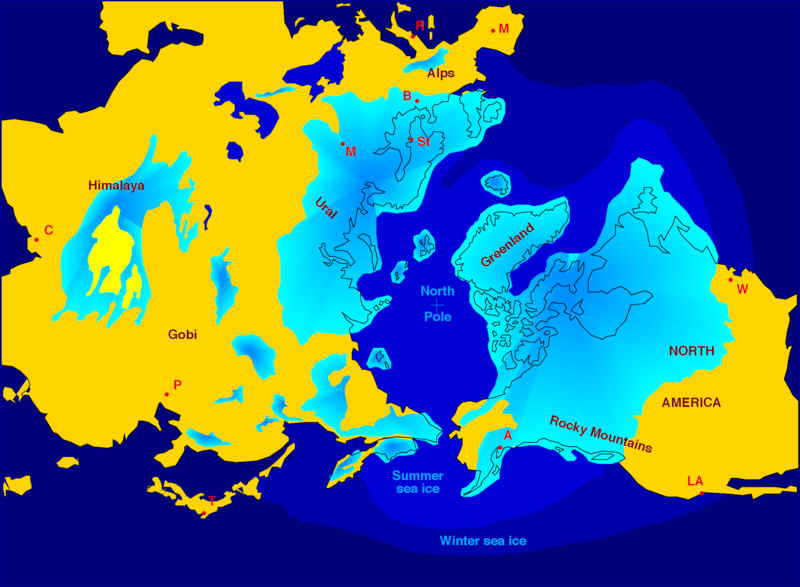

By about 500,000 years ago ice sheets covered most of North America and western Eurasia. As the planet experienced periodic warming and then cooling trends, between about 500,000 B.C. and 8000 B.C. these ice sheets either advanced or retreated. The colder periods, when the ice advanced southwards, are called glacials. Glacial periods usually last between 40,000 and 60,000 years. The warmer periods in between glacials, which last about 40,000 years, we call interglacials.

Northern hemisphere glaciation during the last ice ages. Taken from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ice_age

To a considerable extent, human development was closely attuned to these

shifts in climate, and their consequent transformations of the environment. The

advance of the ice during glacial periods served to bring moisture to previously

dry areas in both Eurasia and North America. When the ice sheets retreated,

these areas then became vast grasslands, able to sustain the kinds of animal

populations upon which early humans increasingly depended for food. As the herds

moved north, following the retreating ice, so too did humanity.

Probably copying the animals themselves, which with their thick hides and

body hair were able to live close to the ice sheets, human beings also began to

learn the uses of clothing to keep warm in these cooler climates. Fire too

permitted them to live in colder regions. Then, when the ice began to move south

again, during glacial periods, humans moved with it.

At the same time, as the ice grew thick and advanced during glacials, it

locked up so much of the earth's water that the level of the oceans and seas

dropped significantly, exposing new lands for human occupation. In some areas

land bridges appeared, connecting regions that had previously been covered by

water. Moving across these appearing and disappearing land bridges, probably

still following the roaming herds of animals, at different times humans

inhabited the Americas, the British Isles, Indonesia and even Australia.

During warmer periods, when the melting ice raised the sea levels and

covered these land bridges, some of these human populations were cut off from

their fellows, isolated in their new homes. In these new regions, as before,

they had to adapt to local conditions. Thus, over extended periods of time,

human beings interacted with their changing environment, learning new techniques

of adaptation and survival.

TOOLS

AND HUMAN SURVIVAL

A major feature of humanity's

capacity for cultural adaptation to their environment was their growing ability

to change the environment to suit themselves. Crucial to this ability was the

development of tools. Even before the appearance of modern humans, earlier

hominids had learned how to use objects in the world around them, such as

sticks, stones, even bones, to expand the range of their own physical abilities

in extracting necessary resources from the environment. For example, a stick

might be used to extract termites from their large mounds, providing early

people with a nutritious snack. The stick had thus become an extension of the

individual's arm and hand that increased their efficiency. Unlike other species,

however, eventually modern humans learned to use certain objects to create other

objects. Stones could be used to chip other stones, thereby giving them a sharp

edge. The sharp-edged rock could then be used as a more efficient means of

killing small animals, or scraping hides for clothing. Such discoveries marked

the beginnings of technology.

Technology greatly accelerated humanity's capacity for cultural adaptation to the environment. Modern humans learned to use tools in ever more complicated forms. Soon they used stones to sharpen and polish other larger stones, fashioning hand axes, as well as a variety of other stone tools. Eventually, they began to combine sticks and sharpened stones, creating more complex and versatile tools.

The era in which such stone tools were humankind's primary technology is

usually divided by scholars into three great stages: the Paleolithic,

meaning Old Stone Age; the Mesolithic,

or Middle Stone Age; and the Neolithic,

or New Stone Age. These terms refer not to ages of time, but to the development

and use of particular kinds of stone tools. Thus some peoples in the world may

still be living in the Old Stone Age while others are in the New Stone Age, or

have left the ages of stone tools altogether because they have discovered how to

make tools out of various metals, or, more recently, man-made materials like

plastic.

Other discoveries and inventions also allowed early humans to interact

with their environment in more adaptive ways. Perhaps the most important was

learning how to make, control and to use fire. As we have seen, the ability to

make and use fire allowed humans to survive in colder climates than they were

naturally used to. As they learned that fire could be used to cook their meat,

they also unknowingly increased their intake of protein. Cooking meat helps to

break it down for the body's digestive system, which is then able to absorb more

protein from the meat than would be the case if it were raw. Increased levels of

protein, the basic building-block of the human body, may well have contributed

to the biological evolution of the human species, particularly the increase in

overall size and brain capacity. This in turn contributed to the human capacity

for cultural development.

In fact, fire also seems to have been a major factor in human cultural

development very early on. It became a centerpiece of human existence. It

changed night into day. It kept other predators away. Not least, eventually

people discovered that they could use fire to change the properties of physical

materials like rocks and clays in ways that made them much easier to fashion

into tools. Moreover, by seeming to change one substance into another, that is

wood into flame, smoke, and ash, it may even have contributed to early human

ideas about the power of nature, and the hidden forces within the world - forces

that waited only to be let out by the right sequence of actions.

In a world in which things that moved were alive and things that did not

were dead, to early humans fire itself must have seemed to be the living spirit

of the wood set free. If it could be done with fire, then why not with other

spirits, trapped in physical forms? If we consider that its early discovery was

probably a result of something as spectacular, violent, and inexplicable as a

bolt of lightning sent from the heavens, the mark fire made on the human

imagination begins to make sense. Along with wind and rain, and other natural

occurrences of the environment that had no obvious cause or source, fire may

well have inspired developments within the early imagination of humanity that

marked the first steps towards religious ideas. For those who did not understand

it, it must have seemed punishment from on high; but for those who learned to

master and use it, fire must indeed have seemed a gift from the gods.

HUNTERS

AND GATHERERS

Humanity has lived by far the

vast bulk of its existence on planet earth as Hunters and Gatherers. During this

phase of human history, human beings probably lived and roamed the planet in

small groups or bands, most members of which were related to one another. Archeologists,

scientists who look for the past record of humanity by digging up the remains of

their settlements or camps, suggest that these bands tended to number between

about twenty and sixty.

There is some evidence that such bands were in contact with others,

though how often is not certain. They seem to have exchanged certain items, like

shells and perhaps stone tools, though we do not know whether this was a matter

of gift-giving, payment, or part of some religious or social custom. They may

have intermarried. Intermarriage among bands would have helped to improve the

chances of survival by increasing the gene pool, and with it the available

hereditary characteristics that determined environmental adaptability.

Over the years, through countless generations, Hunters and Gatherers

learned and passed on the knowledge it took to survive in a natural environment.

Eventually, their survival skills became as finely tuned to the requirements of

their circumstances as those of any modern brain surgeon. The difference is that

hunting and gathering skills are more general

skills, while those of a brain surgeon are specialized skills.

Even among Hunters and Gatherers, however, specialization did occur.

Crafting stone tools, for example, became a fine art, probably practiced better

by some than others. Also, there may have been a general division of labor

between men and women. Men probably did most of the hunting, though perhaps not

all, while women were primarily gatherers. In part this would have been due to

the fact that women bore and nursed the children. Hunting with a small child

clinging to one's shoulder would have been difficult to say the least. Women

without children of course, may also have hunted.

At first, gathering was probably a more leisurely activity in which

everyone participated as they chose: men, women, and children. Once a kill had

been made there was no need to hunt further for the day, and a handy snack of

termites or beetles, or perhaps nuts and berries, must have appeared just as

attractive to men as to women. After all, there were no set hours or set quotas

for production, other than those imposed by a grumbling stomach.

As humans learned to hunt larger and larger animals, however, this early

division of labor probably began to become more refined. Larger game would have

required advanced organizational skills and better technology. As more and more

time was taken up preparing for the hunt and in the hunt itself, men must have

had less time to participate in gathering activities. Consequently, women

probably became the primary gatherers for the group while men became the primary

hunters. (Interestingly, while there is evidence that meat was the preferred

food, the bulk of people's diets in this era actually seems to have come from

gathering.)

COMMENTARY

For a long time, many scholars

believed that the life of Hunters and Gatherers was a rather miserable one, in

which they spent their entire time looking for food, in constant fear of natural

predators or attacks by other bands of humans. More recent analyses, however,

based in part on studies of present-day Hunters and Gatherers, suggest that far

less time may have been spent in food gathering or hunting among these peoples

than is true for people in modern cities. Some scholars have gone so far as to

suggest that the daily existence of Hunters and Gatherers is virtually idyllic,

with none of the stress and strains of modern life; a veritable paradise in

which the rule was cooperation among human beings who experienced virtually no

strife.

Drawing on present-day examples of Hunting and Gathering groups,

particularly the San peoples, or Bushmen, of Southern Africa, some revisionist scholars,

scholars who try to reinterpret the historical record in fundamentally new ways,

believe that Hunters and Gatherers developed largely egalitarian societies, in

which there were no personal possessions, and everyone shared everything in

common.

As evidence of the cooperative nature of such societies, they sometimes

cite the remains of one early man who was found to have had severe arthritis and

other crippling physical conditions although he lived a relatively long life.

His survival, so the argument goes, would have been impossible without the

assistance and care of his fellows. To draw from this kind of evidence general

rules about the kindly, cooperative nature of early human beings, however, may

be an overly generous leap of the modern imagination.

Using present-day Hunters and Gatherers as sources for our conclusions

about bands living over thirty thousand years ago is rather daring. After all,

modern bands have had another 30,000 years of experience in which to learn the

cultural lessons and advantages of cooperation. Given the relatively slow pace

of change in their lives, it has been tempting to some scholars to assume that

these societies are static, not changing at all. This is simply not the case. In

the last 8,000 years, for example, the San of Africa have been steadily hunted

by other groups of humans nearly to extinction. In the process, they have also

been pushed into relatively isolated and less productive territories: an

environmental change that may well have forced them to cooperate more

intensively in order to survive.

While it is probably true that early hunting and gathering societies were

more cooperative than competitive, at least within the group, it is still

extremely likely that some distinctions developed among individuals. The best

hunters, for example, almost certainly got the best bits of meat from their

kills for themselves and their immediate family members. In addition, there may

well have been periodic strife among bands of humans, if not within them. After

all, tools for hunting game could also become weapons of war. In short, everyday

life for earlier Hunters and Gatherers was probably not nearly as rosy as some

recent accounts suggest: according to most estimates, the life expectancy of

Paleolithic peoples was about 20 years or less.

The fact is we simply do not know enough about these early people to do

more than guess. And however educated our guesses may be, with the scanty

evidence available, modern scholars may easily fall into the trap of bias,

reading the historical record according to their own preconceived notions of

what they want to find, rather than what it actually contains.

When confronted by the more romantic interpretations of a hunting and

gathering existence, it is perhaps worth asking how many modern people today

would really prefer life in the open savanna of Africa to their centrally-heated

and air-conditioned homes, with the super-market and the movie theater just down

the street, and the television on in the living room, and a hot bath at the end

of the day? Of course, modern people have paid a price for such things: longer

work hours, problems of pollution, stress, perhaps even the tragedy of war. The

question for all of us is whether the benefits outweigh the costs. While each

type of existence has its appeal, each surely also has its problems.

Having said this, however, it remains to be asked why the Hunting and

Gathering stage, which comprised over 99% of human history, did indeed

eventually give way to other types of existence? As we shall see in the next

chapter, the answer lies in two areas: one beyond humanity's control -- a

changing environment; and the other very much within their control - their

response to the changes. In the course of adapting to this changing environment,

humanity took its first steps out of the Paleolithic Era, out of its infancy

according to some, out of the Garden of Eden according to others, and onto a

road that would lead it in starts and stops and starts again to where we now

are.