Chapter 24 Growth of Colonial Nationalism, 1880-1939

Section

2 From Empire to Commonwealth: the Transformation of the British Empire

In the last quarter of the 1800s new senses of identity were beginning

to emerge among colonial peoples of the British Empire. As colonists in

the so-called White Dominions began to develop national identities of

their own, they also sought a new relationship with Great Britain. In an

effort to acknowledge the aspirations of these colonial nationalists,

and at the same time maintain the unity of the empire, British leaders

began to transform the nature of the imperial relationship.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/33/British_Empire_evolution3.gif

The Question of Dominion Status

As Britain extended self-government to its colonies of settlement in the 1800s, the shape of its empire began to change. Around the world, people of British descent remained bound to the mother country through a common language, legal system, political structures, and general cultural background. At the same time, as the colonists adapted to their unique local conditions, they began to develop their own new identities.

Even with full self-government, or “dominion status” as it began to be called in the early 1900s, many in the colonies felt restricted by imperial ties. The British Parliament could still pass legislation for the dominions and veto colonial legislation. Not least, the dominions remained dependant on Britain for defense.

Even before World War I, British and colonial leaders

periodically discussed the nature of dominion status and the

relationship between the dominions and Britain in what became known as Imperial

Conferences. Despite the efforts of imperialists, however, colonial

nationalism gradually proved stronger than imperial unity. Canadian

Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier probably spoke for most in the

dominions when he declared in 1900:

“I claim for Canada this, that in

future, Canada shall be at liberty to act or not to act, to interfere or

not to interfere, to do just as she pleases, and that she shall reserve

to herself the right to judge whether or not there is cause for her to

act.”

Perhaps the most striking resistance to a strongly united empire, however, came in South Africa. After the Boer War, Sir Alfred Milner, the British High Commissioner, had done his best to destroy the Boer cultural identity and replace it with a British one. In the face of such a challenge, outraged Boers, or Afrikaners as they began to call themselves, reasserted their sense of identity by creating a whole new nationalist mythology. They rejected English and adopted Afrikaans as their national language. They also emphasized their own brand of Dutch Calvinism, insisting that God had ordained that they should rule South Africa as they saw fit.

Taking advantage of the liberal terms of the peace treaty, under two former Boer generals, Louis Botha and Jan Smuts, by 1910 moderate Afrikaners had even united all South Africa into a new dominion—the Union of South Africa—under Afrikaner control. Other Afrikaners, however, remained adamantly opposed to such accommodations with the hated British. In 1912, these anti-British, anti-empire Afrikaners joined together to form the Afrikaner Nationalist Party. Their ultimate hope was to sever the imperial connection altogether and transform the Union into an independent republic.

World War I and Its Consequences

World War I brought to a head all the discussions about the nature of the relationship between Britain and the dominions. In 1914, on the advice of the British Government in London, King George V declared war on behalf of the entire British Empire without consulting the dominion governments. Nevertheless, the dominions generally responded loyally. Prime Minister Andrew Fisher of Australia, for example, pledged Australian support for Britain “to the last man and the last shilling.”

Not all in the dominions, however, liked the implication that

they could be plunged into war by Britain without consultation. For

example, Sir Wilfrid Laurier complained that issues of war and peace

should be for “the Canadian people, the Canadian parliament and the

Canadian government alone to decide.”[7]

When the Conservative Canadian Government of Sir Robert Borden

introduced conscription in 1917, French Canadians resisted it vigorously

and the Liberal Party under Laurier split over the issue. As one

Canadian historian observed, this issue “introduced into Canadian life

a degree of bitterness that surely has seldom been equalled in countries

calling themselves nations.” In South Africa, strong pro-German and

anti-British sentiment even led to the outbreak of rebellion among some

Afrikaner nationalists that had to be forcefully suppressed by the Union

government.

The Commonwealth ideal. During the war, many people in the dominions

began openly to question the nature of their relationship with Britain.

General Smuts of South Africa explained his own views to members of the

British Parliament in 1917:

“I think the very expression

‘Empire’ is misleading. . . .We are not an Empire. Germany is an

empire, so was Rome, and so is India, but we are a system of nations, a

community of States and of nations far greater than any empire which has

ever existed. . . . a number of nations and states almost sovereign,

almost independent, who govern themselves . . . and who all belong to

this group, to this community of nations, which I prefer to call the

British Commonwealth of Nations.”

Colonial leaders continued to press for clarification of the nature of dominion status after the war. At the Imperial Conference of 1926 Lord Balfour, former British prime minister, presented a report which finally defined the dominions as “autonomous communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any respect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.” The Balfour Report also laid down procedures for colonies to progress to dominion status within the Commonwealth. In 1931, Parliament legally enacted the provisions of the Balfour Report in the Statute of Westminster.

Neither the Imperial Conferences nor the Statute of Westminster

resolved all the problems of the new Commonwealth. Important questions

remained. For example, were non-European dependent colonies eligible for

dominion status and commonwealth membership? The first major challenge

to the ideal of Commonwealth unity, however, came in a territory the

British never considered part of the empire at all—Ireland.

Ireland

Since the days of the Normans, the Irish had persistently resisted conquest by England. For centuries, the English Crown had just as persistently tried to bring Ireland under its rule—through conquest and even through colonization, including the wholesale transplantation of Scottish Protestants to settle the northern counties of Ireland in the 1600s. Despite Irish nationalist uprisings in the 1700s, in 1801 the British united Ireland with the rest of the United Kingdom of Great Britain. Thereafter, Irish representatives were elected to the British Parliament in London.

Political unification only increased the determination of Irish nationalists to gain their freedom from English rule. In the late 1800s, some pursued their goals of independence in the British parliament.[8] The most famous Irish political leader, James Parnell, made the question of Home Rule for Ireland one of the most bitterly contested issues of British politics in the late 1800s – an issue that could (and did) make or break individual political careers and even governments.

Just as cultural movements like that of the Grimm brothers had fired German nationalism, so too Irish nationalism was fuelled by a revival of interest in Irish literature, art, and language. The great poet William Butler Yeats and others, for example, reintroduced people to the old Celtic mythology of Ireland and inspired a general movement known as the Celtic Revival. The Celtic Revival in turn encouraged a new sense of Irish national identity.

The question of Home Rule for Ireland—in effect dominion status—remained such a burning issue in Britain’s domestic politics that on the eve of World War I it was very nearly the cause of civil war. Between 1911 and 1914, the Liberal Government finally moved to enact Home Rule. Meanwhile, however, die-hard Conservative Unionists adamantly opposed to any split between Ireland and Britain that would leave the Protestant minority at the mercy of the Catholic majority in Ireland gathered arms to resist Home Rule by force. As tensions rose, the king himself called a conference at Buckingham Palace to try to avert full-scale civil war. In the event, the outbreak of war with Germany prevented the confrontation.[9] During the war, the British Government did finally promise Home Rule for Ireland, though it also floated the idea that the Protestant population of the northern six counties, known as Ulster, might be allowed to remain a part of Great Britain. Such compromise measures only reinforced the opinion of many Irish nationalists that Britain would never really let Ireland go.

In 1916, a band of Irish nationalists intent upon full independence rose in revolt in Dublin in what became known as the Easter Rebellion. British troops put down the revolt and executed its leaders, thus turning them into martyrs for the cause of Irish independence. When the Irish nationalist party, Sinn Fein swept the Irish elections in 1918, the newly elected members of the British parliament proclaimed themselves instead the Dail Eireann, or Irish Parliament, and pledged to establish a republic in Ireland. Britain refused to recognize them and tried to repress the revolt. For several years bloody fighting went on between Irish nationalists and the notorious Black and Tans, special British anti-terrorist units. Finally, in 1921 the British offered the fatal compromise—dominion status for the 26 southern counties with a Catholic majority population. The six northern counties, however, which had a Protestant majority, would remain part of the United Kingdom.

As the British made it clear that all-out war was the alternative, Sinn Fein leader Arthur Griffith agreed and in 1922 Britain recognized the Irish Free State as a fully self-governing Dominion. Some Irish nationalists, however, saw both partition and dominion status as a betrayal. A brutal civil war broke out in Ireland. Although the Free State prevailed, in the 1930s Eamon de Valera, leader of the die-hard nationalists, was elected prime minister of Ireland. Methodically, he dismantled all vestiges of dominion status. Finally, in 1936, the Dail proclaimed Ireland to be a “sovereign, independent republic.” For extreme nationalists, however, Ireland would not be truly free and independent until the northern counties had been ‘liberated’ from Britain’s rule and reunited with the south.

The Case of India

Perhaps the greatest challenge to conceptions of the Commonwealth came from India—the most important and largest of Britain’s non-European possessions. India presented the British with their greatest dilemma. Should it become a self-governing dominion or not? Staunch imperialists usually answered no. They agreed with Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, who once observed: “As long as we rule India, we are the greatest power in the world. If we lose it we shall drop straight away to a third-rate power.”[10]

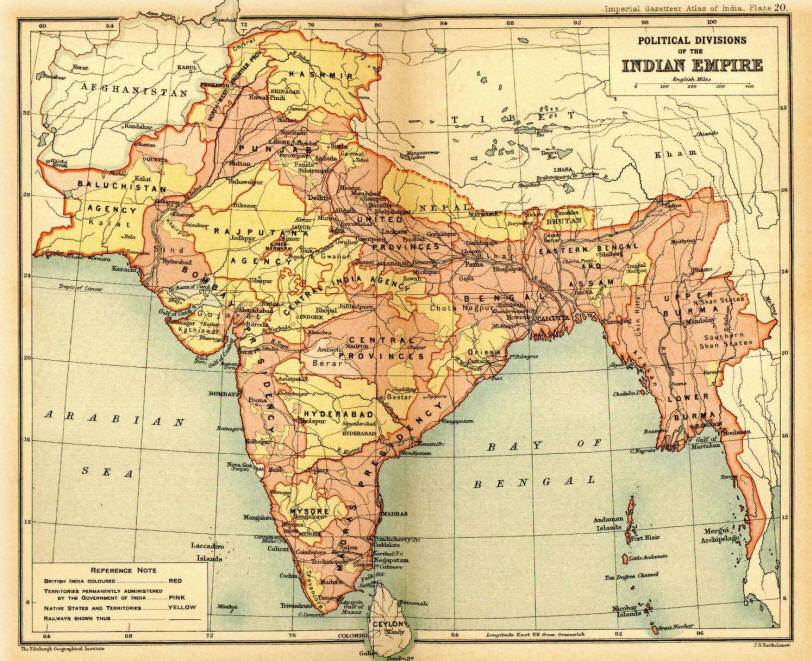

Many Indians also preferred to keep things as they were. In fact,

India was not a single colony at all but a hodgepodge of many different

states—an empire in its own right. Some of these states were ruled

directly by the British, but many others—the so-called “princely

states”—remained largely autonomous under their hereditary rulers,

with the Government of India handling their foreign affairs. In

addition, British imperial rule helped maintain a rather uneasy truce

between the Hindu majority and the large Muslim minority. Many Muslims

preferred British rule to a “Hindu Raj.”

Early Indian nationalism. There were some Indians, however, who

hoped that India would achieve the same self-governing status as the

dominions. These early Indian nationalists were members of that

western-educated class whom early imperial reformers such as Macaulay

had hoped to create to help Britain rule India. Initially they had no

desire to see an end to the British raj. Pherozesha Mehta, an English

trained lawyer and justice of the peace from Bombay, expressed the

feelings of many when he wrote:

“When in the inscrutable dispensation

of Providence, India was assigned to the care of England, she decided

that India was to be governed on the principles of justice, equality and

righteousness without distinctions of colour, caste, or creed.”[11]

Such moderate views and the appeal to Britain’s own sense of fair play also drew many liberal Britons into the cause of greater Indian participation in the government.

Despite such optimism, however, most of the British in India remained wary of giving Indians equality. In 1883, for example, the Liberal Viceroy Lord Ripon enacted the Ilbert Bill, which would have given Indian judges jurisdiction over Europeans in Indian courts. The outcry within the British community in India was so great, however, that the government finally withdrew the bill and left Europeans answerable only to European judges. Such blatantly racist treatment contradicted the principles of English law western-educated Indians had learned in school. The episode convinced many, including more liberal British officials, that they must organize properly if they wanted the government to take them seriously.

In 1885, Allan Octavian Hume, a retired member of the Indian Civil Service, invited western-educated Indians from all over the sub-continent to meet in Bombay. There they established the Indian National Congress, the first all-India political organization.[12] The delegates declared their loyalty to the Queen-Empress Victoria and called for equal opportunity for Indians and British to serve in the government of India. As an organization of the small western-educated Indian elite, however, the Indian National Congress had little success. One British viceroy called it, with some justification, “an infinitesimal and only partially qualified fraction [of the] voiceless millions.”[13]

As the British resisted even the moderate demands of the Indian

National Congress, some Indian nationalists called for a stronger

approach. For example, Balwabtral Ganghadar Tilak, an influential Indian

journalist, called for cultural resistance to the British through

festivals celebrating Hindu gods and heroes of the past. Many of

Tilak’s followers eventually resorted to violence to gain Indian

demands. The growth of militant Hindu nationalism in turn worried many

Muslims. In 1906, Muslim leaders established their own Muslim

League[14]

to “protect and advance the political rights and interests of the

Mussulmans [Muslims] of India.”[15]

The Home Rule League. Before World War I, the British responded to growing nationalist demands with a series of reforms that brought Indians for the first time into high positions in the government—notably as members of the provincial executive councils, as well as to the viceroy’s council and the advisory council of the British Secretary of State for India. Western-educated Indians, however, hoped for more—specifically, they wanted self-government along British parliamentary lines. India’s loyal participation in the war effort during World War I made such demands more difficult for the British to deny. In 1916 two separate Home Rule Leagues, patterned after the Irish Home Rule movement, sprang up under Indian and liberal English leadership. In 1917, the Muslim League joined the Congress in the so-called Lucknow Pact, also calling for Indian Home Rule.

After considerable deliberation, in August 1917 the British

Government finally announced their long-term policy for India: “the

gradual development of self-governing institutions with a view to the

progressive realization of responsible government in India as an

integral part of the British Empire”[16]—in

other words, dominion status. Even as the British declared their new

policy, however, a major incident in the city of Amritsar transformed

the situation.

The Amritsar Massacre. In response to terrorist actions by radical Indian nationalists, in 1918 the British had begun to impose strict security regulations. Protests against these regulations had led to violence in the Punjab, where four Europeans were murdered by a mob in the city of Amritsar. The local British commander immediately banned all public meetings. When a large group of Hindus who had not heard about the ban gathered in a walled field for a religious festival, the British commander ordered his troops to open fire. Some 400 men, women, and children were killed and over a thousand wounded.

The Amritsar Massacre

shocked both Indians and British alike.[17]

When a formal enquiry faulted the British officer in charge but failed

to punish him severely, many nationalists decided that the British must

leave India once and for all. Perhaps the most influential was a

bespectacled 49-year-old English-trained Indian lawyer named Mohandas K.

Gandhi.

[18]

Gandhi. [BIO]Born in western India in 1869, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was the son of the hereditary prime minister of a small Hindu state. Unlike most of the Congress leaders, Gandhi was not a Brahmin but a member of the merchant class, or Vaisya. While still young, his parents sent him to study in London. There he read law and eventually became a barrister, or lawyer. While in London, Gandhi was heavily influenced by liberalism, as well as Christianity. His introduction to Hinduism came from the Theosophical Society, a Western organization devoted to reconciling eastern religious traditions with modern Western science.[19]

After briefly practicing law in India, in 1893 Gandhi moved to South Africa to join a law firm.[20] In London Gandhi had come to think of himself as a citizen of the British Empire. In South Africa, however, he confronted the racist attitudes that many white South Africans, both British and Afrikaner, held toward non-Europeans. Outraged by this racial prejudice,[21] in 1906 Gandhi began his first campaign of satyagraha (“holding fast to the truth”), or peaceful noncooperation with the government, in order to improve the plight of South Africa’s large Indian community.[22]

In 1914, at age 46, Gandhi returned to India, where he eventually began to try his tactics out against the Indian Government. Although he publicly supported the British war effort in World War I,[23] the Amritsar massacre convinced Gandhi that India must not only achieve self-government but complete independence. Realizing the need for broad popular support, he reminded the western-educated Congress members of their roots in traditional Indian society. In 1921,[24] Gandhi himself first appeared not in western clothing but in the traditional loincloth and homespun shawl of an Indian peasant. As he launched satyagraha movements in India, he inspired thousands of followers.[25] His followers gave him the title of Mahatma, or “great soul.”[26]

By using symbolism most Indians could easily understand, Gandhi

transformed the Congress into a popular political movement with mass

support. In 1930, for example, he led thousands of Indians on a march to

the sea to make salt—as a protest against the government’s monopoly

on the manufacture and sale of the vital substance. He also encouraged

Indians to spin and weave their own cloth as a means of protesting

government policies that favored British manufacturers.

Constitutional developments. Even as Gandhi transformed the Indian National Congress into a mass movement, the British were quietly carrying out major constitutional changes. In 1919 they drafted a new constitution that transferred some powers in the provincial governments to Indian ministers responsible to elected legislative councils—a dual system known as dyarchy. At the center an elected Legislative Assembly and Council of State were also put in place. Under pressure from religious minorities, special seats were reserved for Muslims at all levels of the new system, as well as for Christians, Jains, and others—a policy many in the Congress opposed. When the system went into effect in 1921, one British leader observed: “The principle of autocracy has been abandoned.”[27]

Despite this steady movement toward representative government, under Gandhi’s leadership Congress persistently demanded more. When Britain enacted a new federal constitution for India in 1935 that provided limited Home Rule, Gandhi and the Congress continued to demand total self-government, even as Congress candidates swept the elections and formed governments in most of the provinces.

Not all Indians accepted Gandhi's leadership or methods, however. Extreme Indian nationalists continued to use violence in an effort to drive the British from India. Muslims, on the other hand, accused Gandhi of trying to substitute a “Hindu raj” for the British raj. Under the leadership of another British-trained lawyer, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who became head of the Muslim League, eventually the League demanded the creation of a separate Muslim state should India become completely independent.