Chapter 2 The First Civilizations

Section

3

Like Mesopotamia and Egypt, the first

civilizations in India and China developed in the basins of great rivers.

The

first civilization of which we have so far found evidence on the Indian subcontinent

developed in the Indus River valley of present-day Pakistan. In China the first

signs of civilization are found in the Huang He and Yangtze River Valleys. While

the first Indian civilization developed into a complex urban culture early on,

the first Chinese cultures did not develop cities until much later. Uncovering

information about life in early India and China has been more difficult than

learning about ancient Mesopotamia or Egypt.

INTERNET RESOURCE: The Indus Valley Civilization

The

Indus River Valley

The Indus Valley is a broad plain hemmed in by desert to the east and mountains to the west. Geographically, it is much like the valleys of the Nile, the Tigris and the Euphrates. The flooding of the river provides both the water essential for agriculture and enriching silt that replenishes the soil. With its source in the Himalayas, the Indus River floods when the mountain snows melt in the spring. It also floods when the monsoons, seasonal rain-bearing winds, bring heavy rains to the western Himalayas. Otherwise, the surrounding land is relatively dry and may be easily cleared for settlement and agriculture, even without the use of iron tools.

Given such ideal conditions, it is perhaps little wonder that by about 3000 B.C. people lived along the Indus River in small, widely scattered villages of mud-brick houses. Although these people mainly used stone tools, they were also beginning to use metals such as copper. As in Sumer and Egypt, the production of surplus food by means of irrigation agriculture seems to have led to the development of cities in the Indus River Valley. By about 2500 B.C. a full-fledged civilization had emerged.

http://www.harappa.com/har/gif/ancient-indus-map.jpg

Harappan Civilization. The two most important cities in the Indus Valley civilization were Mohenjo-Daro on the lower Indus, and Harappa, 400 miles to the northeast. Harappa has provided archaeologists and historians with so much evidence of early Indus Valley life that they have named the civilization in this area Harappan civilization. From about 2300 to 1750 B.C. Harappan civilization expanded over an area larger than all of Sumer. Despite its enormous expanse, the civilization was remarkably uniform. Weights and linear measures were the same throughout the region, as were the types of copper and bronze tools people used. Many scholars believe that such uniformity of cultural elements also points to some sort of political unity in the region.

Whether

the entire region was unified politically or not, the cities of Harappa and

Mohenjo-Daro at least were extraordinarily well planned according to highly

sophisticated designs. Each city had a population of about 35,000 - all of whom

lived in an area roughly a mile square. Each city had a strong central fortress,

or citadel, to the west, while to the east lay the houses and public buildings.

Each city was also laid out on a grid pattern, so that streets intersected at

right angles.

The

buildings of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were designed for practical use. Many were

constructed with durable burnt bricks that had been baked in kilns, or ovens –

a process that made them far stronger than the sun-dried bricks commonly used in

Mesopotamia. Houses faced inward on open interior courtyards apparently to

ensure privacy, but also perhaps for security. The walls along the main streets

were solid brick, broken only by openings for drainage chutes. Almost every

house had its own bathroom, with brick floors and covered drains that carried

wastewater to the main street drains of the city's water removal system. Some

homes had their own wells, while others used public water sources. The

engineering skill demonstrated by the Harappans in these water and drainage

systems would not be matched again until the time of the Roman Empire, over two

thousand years later.

A narrow lane at Mohenjo-daro (left), http://www.mohenjodaro.net/images/mohenjodarostreet63.jpg; the Indus River at Mohenjo-daro (right), http://www.mohenjodaro.net/images/indusriver2.jpg

Although

Harappan civilization was apparently urbanized and sophisticated, farming

remained essential to the survival of city residents. The most important crop

was wheat, but farmers also grew barley, peas, dates, and mustard seeds. The

Harappans also kept a wide variety of animals, including cattle, pigs, goats,

and sheep. City-dwellers worked primarily in industry or trade. Indus Valley

artisans produced fine articles, including excellent cotton cloth, painted

pottery, artistic bronze sculpture, copper and bronze weapons and tools, and

gold and silver jewelry. As early as 2500 B.C. they appear to have been trading

these goods with Mesopotamian merchants.

Although for many years scholars assumed that the people of the Harappan civilization had developed a writing system comparable to those of Egypt and Mesopotamia, recent research has challenged this view. Archaeologists have found what appear to be pictographs, usually in the form of cylinder seals, dating from about 2300 B.C. Additional symbols have been found on clay pots and pottery fragments. Unfortunately, no one so far has been able to decipher any of the symbols or to demonstrate definitively their connection with any particular language. Nor do all scholars agree that the symbols actually represent the written form of an spoken language. They may simply be symbols universally recognized throughout the Harappan culture zone - rather like the symbols found on modern traffic signs or in airports, hospitals and other public buildings. Perhaps they represented gods and goddesses, or natural objects such as the sun, moon or stars, or animal spirits, which people used as charms or magical talismans to ward off evil or to invoke blessings and luck. It has also been suggested that the seals were used in trade either as elementary forms of identification, much like the coats of arms of medieval Europeans, or as rudimentary means of identifying and counting products. So far no inscriptions have been found that are long enough to suggest anything like complex documents or literature. On the other hand, as traditional scholarly views have held, they may be a combination of pictograms and ideograms, pictures that convey whole words or ideas, and representations of syllabic sounds, or a combination of all three, like the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt. Without further discoveries and research we can only speculate.

Examples of the Indus Valley script, http://indoeuro.bizland.com/project/script/indus.jpg

If

Harappan society was preliterate it may help to explain why no Harappan temples,

shrines, or religious writings have been found - although scholars believe that the

Indus Valley inhabitants worshipped a great god and used certain animal images

– the bull, buffalo, and tiger – in religious ceremonies. Some evidence also

points to the worship of a mother goddess who apparently symbolized fertility.

There is even a hint in some depictions that the Harappans may have

practiced human sacrifice. It does seem clear that they had some sort of

belief in an afterlife, however, since they generally buried their dead

formally, with personal possessions such as pottery or

jewels. Some were buried in large brick chambers, but most were buried

outstretched

on their backs with their heads pointing north. At the city of Lothal, about 400

miles southeast of MohenjoDaro, archaeologists have found several double

graves, each containing a male and female skeleton.

Harappan

decline. Despite

this rich and thriving culture, the most extensive in the ancient world, the

unity of Harappan civilization shattered sometime around 1500 B.C., for

reasons that scholars continue to debate. For many years, most researchers

believed that invaders had destroyed the civilization. More recently, however,

others have suggested dramatic climatic or environmental shifts may have

precipitated Harappan decline. Some evidence, for example, points to rapidly

occurring changes in the course of the Indus River that might seriously have

disrupted agriculture. Other scholars believe that major earthquakes and

flooding struck the region about 1700 B.C. The discovery of several unburied

skeletons, together with homes and personal belongings hastily abandoned,

seems to indicate some disastrous event at Mohenjo-Daro – though whether it

was environmental or human in origin - or a combination of both - no one can tell. Perhaps the earlier

notions of invasion are not entirely without merit. Without further evidence,

however, we can only continue to speculate and to make educated guesses.

Origins of

Civilization in China

INTERNET RESOURCE: Neolithic China

During

the Neolithic era, the first settlements in China were along the Huang He, or

Yellow River, which flows through the great plain of northern China. In the

valley of the Huang He, nomadic peoples settled in areas between wooded hills

and swampy lowlands, where enough plants and animals existed to keep them alive

even when their farming might not be successful.

The

climate of the Huang He valley. Like other ancient civilizations, Chinese civilization

originated in regions with fertile soil and plentiful water supplies. Over many

centuries the prevailing winds of North China had deposited a fine yellow dust

along the North China Plain. This dust formed into a very rich soil called loess

(LEs), which in some places formed a layer 350 feet thick. This fine yellow dust

was also carried along in great quantities by the Huang He, which got its name

from the yellow silt created by the dust. Much of the silt was deposited on the

riverbed, which made the Huang He too shallow for navigation, though still

useful for irrigation, and created new lowland.

Every few years, particularly after heavy rains, the Huang He would overflow its banks in destructive floods. Raging floodwaters often destroyed everything in their path, turning once usable farmland into waterlogged swamps. Such destructive floods led the ancient Chinese to nickname the Huang He "China's Sorrow." The general climate in the valley of the Huang He was also severe. Winters were long and cold, summers short and hot. Dust storms swept across the valley in the spring. Rainfall too was unpredictable and heavy rains alternated with periods of drought and famine.

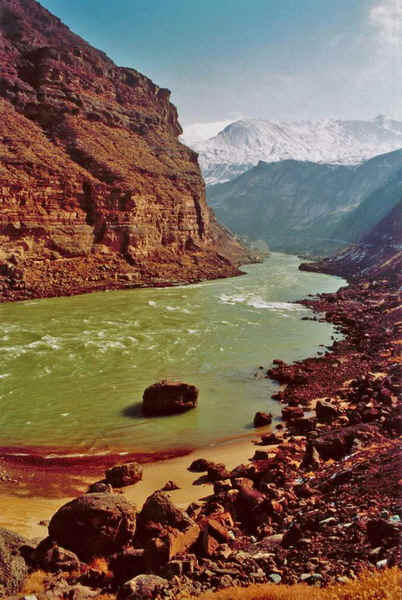

The Huang He near the beginning of the river valley in Qinghai province of northwestern China, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yellow_River

Yangshao

Culture.

The earliest Neolithic culture so far discovered in China is called the

Yangshao, after the village in Henan province, in northern China, where its artifacts were first found.

Between about 5000 and 3000 B.C., Yangshao culture spread over a fairly wide

area around the middle of the Huang He and one of its major tributaries, the Wei

River. Archeologists recognize Yangshao

culture largely by its characteristic painted pottery. Apparently unfamiliar

with the potter's wheel, Yangshao artisans formed their pottery by hand, then

decorated it with pictures of fish, animals, plants and geometric forms.

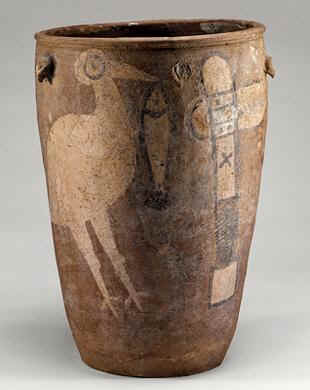

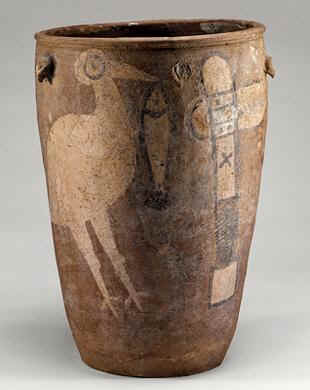

Examples of Yangshao painted pottery, http://www2.hawaii.edu/~kjolly/151/images/Yangshao.jpg; http://www.nga.gov/education/chinatp_sl02.htm

Although

people in the Yangshao culture were farmers, they also hunted and fished. They

relied solely on human labor in their farming techniques, tilling the soil by

hand with hoes since they did not yet have the plow. Millet seems to have been

the most important grain crop, although some villages also grew wheat and even

rice. They also domesticated a number of animals, particularly the dog and the

pig, and later apparently ; they also raised pigs and sheep. In addition,

farmers grew hemp, which they made into cloth, and there is even some evidence

that Yangshao farmers may have raised silkworms.

The

people of the Yangshao culture built their houses in clusters. Some

archaeologists have argued that this suggests a clan structure in which people

lived in groups of related families. If this interpretation proves correct, it

would be the earliest example of the strong, clan-based type of society that is

a feature of later Chinese civilization. At any rate, as Yangshou culture spread

it provided a foundation on which a more sophisticated culture would soon build.

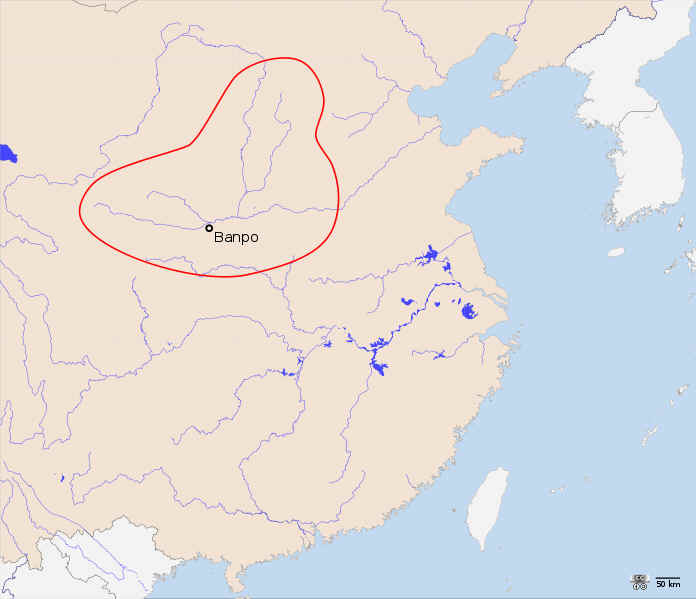

Extent of Yangshao culture, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yangshao_culture.

Longshan

Culture.

Known as Longshan, from the first site discovered by archaeologists in the

1930s, this second Neolithic culture became more complex and widespread than

Yangshao. From about 3000 or 2600 (scholars debate the dating) to 2000 B.C.

Longshan Culture flourished on the North China plain and along the eastern

seaboard of Central China. It also spread over all those areas that had been

part of the Yangshao cultural zone. Since its discovery, modern scholars have

primarily recognized Longshan Culture by its distinctive, highly polished and

delicate black pottery. Unlike Yangshao potters, the artisans of Longshan

were the first in east Asia to use a high-speed wheel on which to throw their

pots. They also fired them in kilns at very high heat.

Example of Longshan Black Eggshell Pottery, http://media-2.web.britannica.com/eb-media/24/42524-004-7415436A.jpg

The

Longshan were also farmers, though unlike the Yangshao they appear to have

depended more heavily on rice cultivation than millet or wheat. Wet-field rice

farming is highly labor intensive and requires enormous coordination to create

the dikes and channels with which to get river water to flood the paddies. On

the other hand, it is also about eight times more productive than millet or

wheat farming. A culture relying on rice can produce greater surpluses and

sustain a much larger population than one relying on other grains.

Even

more important for the development of civilization in China, however, Longshan

Culture was apparently the first to begin to build relatively large fortified

towns. The Longshan people developed a new technology for construction that

involved rammed-earth walls and platforms. As their culture developed, they

increasingly used these techniques to build large walls around their

settlements. From all the archaeological remains, it seems that Longshan

builders also preferred higher ground for their cities, on small hills or

knolls, where they could look down over the plains below. Such strategic

thinking suggests that the Longshan were concerned with defense against enemies.

In

addition to building such major fortified cities, the Longshan also began to use

bronze artifacts. Jade too became enormously important, at least partly as a

symbol of status. While we have no real knowledge of their religious customs,

they practiced human as well as animal sacrifice regularly, and when rulers

died, wives, concubines and other servants were often buried alive to keep them

company in the grave.

Extent of Longshan Culture, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longshan_culture.

Many

Chinese scholars have become convinced that Longshan Culture is the

“mythical” Xia dynasty, which according to ancient Chinese tradition was the

first dynastic state in China. The discovery and excavation of a major city from

the late Longshan period in 2002-2004 at Wangchenggang

near Dengfeng in Henan Province has only reinforced this conviction.

There, archaeologists have discovered sacrificial pits

with human bones, human skulls used in rituals, long hollow pieces of jade

with rectangular sides, and white pottery, which demonstrated the noble status of

the owner. At a nearby site, in 1977, archaeologists had already discovered a

smaller city containing fragments of bronze wares and building foundation pits

containing the skeletons of human sacrifices. They even discovered inscribed

characters that may be a form of writing, though it has so far remained

undeciphered. In short, although we have no written records to guide us,

it seems reasonable to suggest that Longshan Culture was comparable to the

city-states of Sumer. At the very least, it is increasingly clear that Longshan

Culture was indeed the base on which the first historical dynasty, the Shang,

would eventually build.