Chapter 3 Migration and Empire: the Spread of Civilization

By 1700 B.C.,

Egypt had built a strong and magnificent civilization. The Egyptians

took such great pride in their culture that they generally ignored

foreign ideas and practices. In the 1730s B.C.,

however, barbarian invaders moved in and conquered Egypt. This brought

an end to Egypt’s complacency and later inspired an imperial spirit.

The

Hyksos Invasion and Conquest

Like Mesopotamia, Egypt too experienced the effects of the great migrations of the 1700s and 1200s. As elsewhere, the initial stages of the migrations were apparently relatively peaceful. From the northeast, Semitic-speaking peoples began to move into the Nile delta and to settle among the Egyptians.

In about 1730, however, probably in concert with a new group arriving from the east, these Hyksos, as they were collectively known, rose up and overthrew the Egyptian dynasty. The Hyksos brought with them several new technologies that gave them an advantage over the Egyptians – the horse-drawn war chariot, and the secret of casting bronze. Bronze was a much harder metal for making both weapons and tools than the copper used by the Egyptians. Despite these advantages, however, Hyksos rule in Egypt was rather fragile.

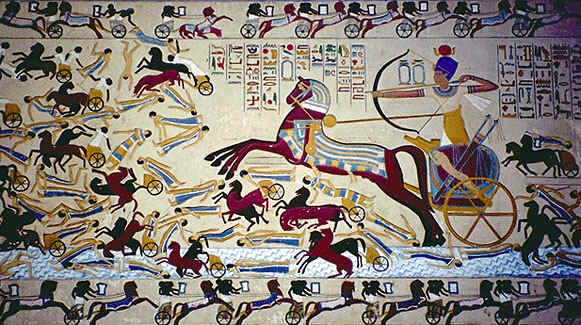

Depiction of Pharaoh Ahmose I defeating the Hyksos, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e6/Hyksos.jpg

Although they adopted Egyptian styles of civilization and tried to rule as traditional pharaohs, the Hyksos remained outsiders in Egypt. In addition, they never ruled directly over the entire Nile Valley, only its northernmost regions. The middle portion of the valley remained under the rule of a Theban prince who paid tribute to the Hyksos. Further south, Upper Egypt became an independent kingdom ruled by Nubian princes. These princes were allies of the Hyksos pharaohs, however, leaving the Theban princes caught in the middle.

By the 1500s B.C., the Theban rulers had mastered Hyksos war technology and tactics. In about 1580, they launched a war of liberation to drive the foreign Hyksos out of Egypt that lasted several generations. After one defeat in battle, the Theban ruler Kamose denounced Egyptians who collaborated with the Hyksos against him, and threatened to “reduce their homes to red mounds because of the damage that they did to Egypt when they put themselves at the service of the Asiatics [Hyksos], forsaking Egypt.” Eventually, in about 1570 B.C. Kamose’s brother and successor, Ahmose, drove the Hyksos out of Egypt once and for all.

The

New Kingdom in Egypt

Two centuries of Hyksos rule showed Egyptians the dangers of ignoring the outside world. After throwing out the Hyksos, Ahmose became the first ruler of the 18th dynasty, and established what became known variously as the New Kingdom or the Empire. The New Kingdom was characterized by imperial expansion and a more cosmopolitan culture.

INTERNET RESOURCE: Discovering

Ancient Egypt

INTERNET RESOURCE: The Ancient Egypt Site

Imperial expansion. The new pharaohs apparently concluded that the best way to prevent Egypt from ever being invaded again was by expanding its borders – in effect, by building an empire. Consequently, they established a standing army. To keep the south secure, they kept the capital at Thebes. With little danger from the desert to the west, Egyptian armies and chariots crossed into Palestine and Syria, conquering territory as far as Asia Minor. The empire grew so great that Pharaoh Thutmose I claimed that Egypt stretched “as far as the circuit of the sun.”

As the empire expanded, Egypt came into greater contact with foreign ideas and peoples. In addition, foreigners brought their customs as well as their wealth to Egypt, helping to create both great prosperity and stimulating cultural diversity. With this new wealth, Egyptian rulers adopted a more imperial style of art—depicting Egypt’s glory and conquest of other peoples. The extent of Egyptian peace and prosperity under the empire was perhaps best illustrated in the reign of one of the few women to rule Egypt in her own right—Queen Hatshepsut.

Statue of Queen Hatshepsut, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Hatshepsut.jpg/150px-Hatshepsut.jpg

The daughter of a pharaoh, Hatshepsut married her half-brother, Thutmose II, who became pharaoh when her father died. When her husband died, his son Thutmose III (Hatshepsut’s stepson) was too young to rule, so Hatshepsut ruled Egypt until he came of age. Although she apparently had the support of her father’s court officials and the priests of Amon-Re, Hatshepsut’s greatest power seems to have come from her own will to rule. Taking all the rightful titles of a pharaoh, she invoked the gods to justify her right to the throne:

Came forth the king of the gods, Amon-Re, from his temple saying, ‘Welcome my sweet daughter, my favourite, the King of the Upper and Lower Egypt, Hatshepsut. Thou art the king, taking possession of the Two Lands.’

Hatshepsut ruled Egypt for 20 years. When necessary, she led Egyptian armies to war, as when incursions by invaders from the south caused her to lead a campaign into Nubia. Generally, however her reign was peaceful and prosperous. She sent commercial expeditions from Egypt down the Red Sea. She was also known for her programs to refurbish temples and other public works projects. After her death in 1482 B.C., however, her stepson Thutmose III had her images removed from her monuments, and replaced them with those of himself and his father.

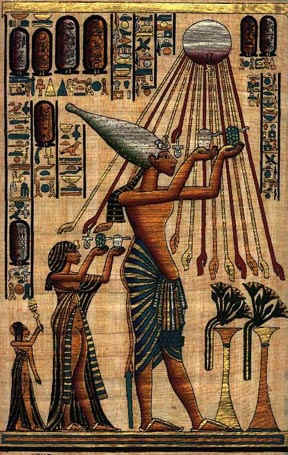

Akhenaton’s religious revolution. The contact with foreign cultures had a great impact on religion in Egypt. In 1380 B.C., the young pharaoh Amenhotep IV came to power. Amenhotep came to believe that the supreme god over all others was the disc of the sun, which he called Aton. Defying the priests of Amon-Re, the chief Egyptian god by this time, he renamed himself Akhenaton, meaning, “pleasing to Aton.” Confronted by continuing priestly resistance, he soon proclaimed that Aton was the only god and suppressed the worship of all others. He also removed the name of Amon-Re from all public inscriptions. Finally, he built a magnificent new capital city at ‘Amarna, dedicated to Aton, which he called Akhetaton.

Akhenaton and his queen, Nefertiti, giving offerings to the Aton, the disc of the sun, http://www.heptune.com/Akhen4.jpg

These changes provoked a backlash from the priests of Amon-Re. Not only did Akhenaton challenge their religious beliefs, but he challenged their power as well. Most of the priests were closely linked with noble families, who held most of the state offices. Moving the government to ‘Amarna weakened their power, and the priests feared that Aton’s followers, who had few links with the aristocracy, would grow stronger at their expense. The conflict over religion thus became also a struggle for power.

The priests of Amon-Re eventually won. The common people had never given up their traditional religion for the pharaoh’s Aton worship. Nor did the aristocracy like it. Akhenaton’s successor, the young Tutankhamen, renounced his belief in Aton during his reign, and soon thereafter Aton’s name was replaced by that of Amon-Re on all public inscriptions. The new capital at ‘Amarna was abandoned and the desert swallowed it up.

INTERNET

RESOURCE: The Amarna Period

Egyptian

Decline

Akhenaton’s religious reforms contributed to the decline of Egyptian power in the 1300s. In his struggle with the priests of Amon-Re, the pharaoh had neglected the empire’s defenses and particularly its territory in Palestine and Syria. Rival powers soon took advantage of the situation. The Hittites, for example, encouraged local people in the northern Egyptian provinces to rebel. The Hittites themselves attacked the Egyptian Empire throughout the next century.

In 1286 B.C., Pharaoh Ramses II engaged in a great battle against the Hittites at Kadesh. Hittite accounts of the battle record an Egyptian defeat. Egyptian sources, on the other hand, claim that Ramses himself single-handedly took on 2,500 Hittite chariots, and with the help of newly arrived troops drove back the Hittite forces, thus achieving victory. Whatever the truth, the real outcome of the battle seems to have been a draw. Before long, however, both the Hittites and Egypt experienced even worse blows from beyond their borders.

The great Temple at Abu Simbel, built by Ramesses II to commemorate his victory over the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh. The massive statues depict Ramesses himself wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. The temple was dismantled and removed from its original location to higher ground in the 1960s to save it from being flooded by the building of the Aswan High Dam and Lake Nasser. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/Abu_Simbel_Temple_May_30_2007.jpg/800px-Abu_Simbel_Temple_May_30_2007.jpg

Renewed

invasions. Beginning in the middle of the 1200s, Egypt, like all the

other states of the region, came under almost constant attack from new

invaders. The Egyptians called them the “Sea Peoples.” Their attacks

basically put an end to the Egyptian empire, forcing the pharaohs to

abandon outlying provinces and to retreat to the delta and Nile valley.

Over the next two centuries, the shattered empire became simply a

kingdom once again. So weak was the reduced Egyptian power that when new

invaders from the West, the Libyans, appeared in the Nile delta in the

late 1100s, they were able to set up independent kingdoms under their

own dynasties. In 950, one of these Libyan dynasties claimed the throne

of Egypt itself and ruled as pharaohs for over 200 years.

Throughout these centuries of

growing insecurity, Egyptian culture began to change. Religion became

less concerned with morality and more concerned with magic rituals and

amulets designed to ward off evil. Instead of having led a good life to

achieve immortality in the hereafter, even ordinary Egyptians now

believed that they could pass into paradise with the right charms and

incantations in their coffins. As the state became less and less a

source of protection and security, loyalty to the state also diminished.

People became less committed to serving pharaoh and more concerned with

their own interests.

The

Nubian dynasty. Meanwhile, up the Nile valley to the south, the

African rulers of the kingdom of Kush began to advance downriver. Kush

had first emerged in the 1800s around the trade routes that connected

northeastern Africa with both Egypt and the Red Sea trade. Heavily

influenced by Egyptian civilization, and for many years under Egyptian

control, eventually the Kushites adopted Egyptian culture

wholesale—worshipping Egyptian gods, using hieroglyphs, and even

building temples and pyramids.

By 730 B.C., Kush had grown powerful enough to sweep north and conquer the kingdom of Thebes. Within the next 20 years, Kushite princes conquered all of Egypt and reunited the country for the first time since the fall of the New Kingdom. Known as the Nubian dynasty, the Kushite pharaohs governed Egypt for a further fifty years. Even the Kushite kings were not strong enough to reverse Egypt’s decline, however, and under the onslaught of Assyrian invasion in 671, the Nubian dynasty also fell. The Kushites themselves abandoned Egypt and withdrew to Nubia, where they established a new capital at Meroe and began to rebuild their kingdom.